Chef to Chef Los Angeles New York

Anajak Thai’s Justin Pichetrungsi on What It Means to Be Unapologetic

Welcome to Chef to Chef, wherein Resy empowers chefs to interview other chefs.

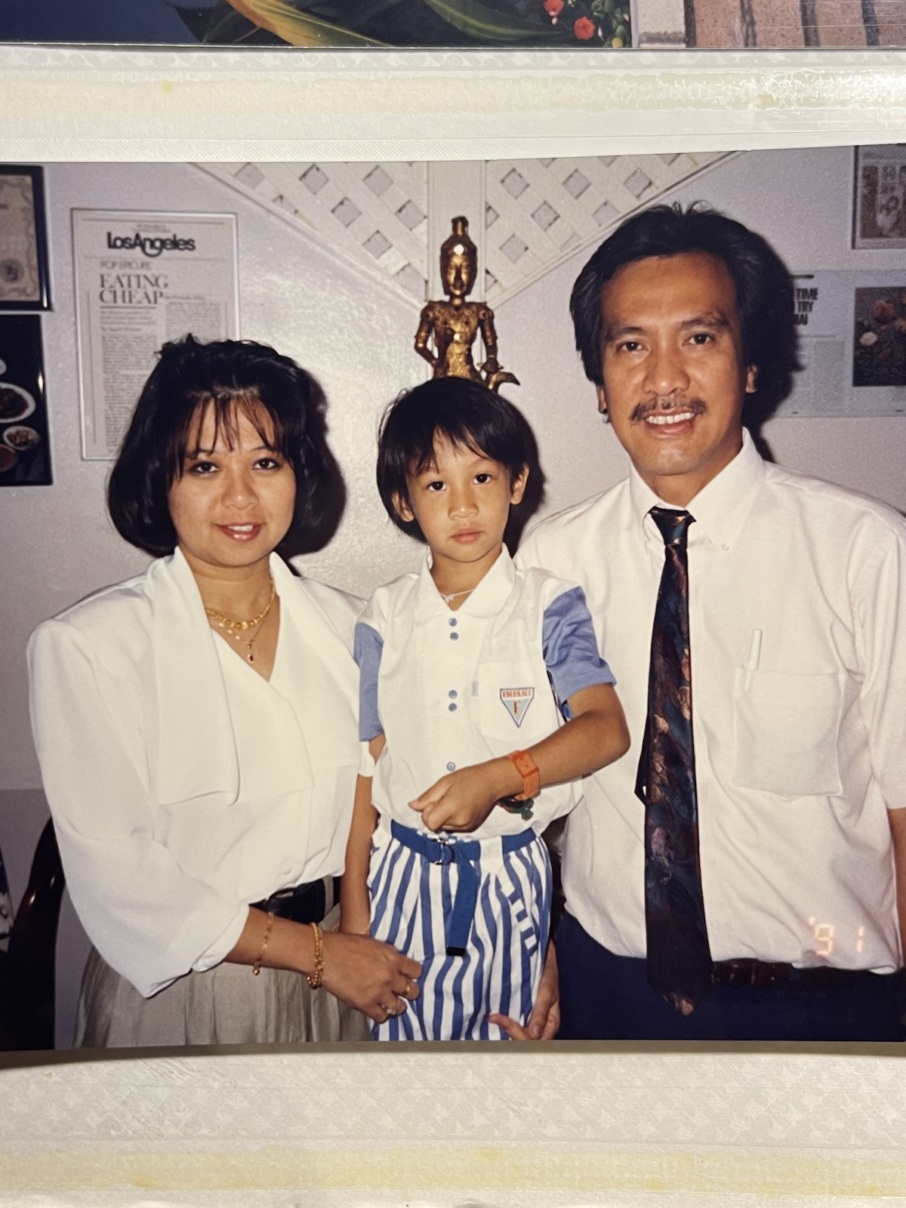

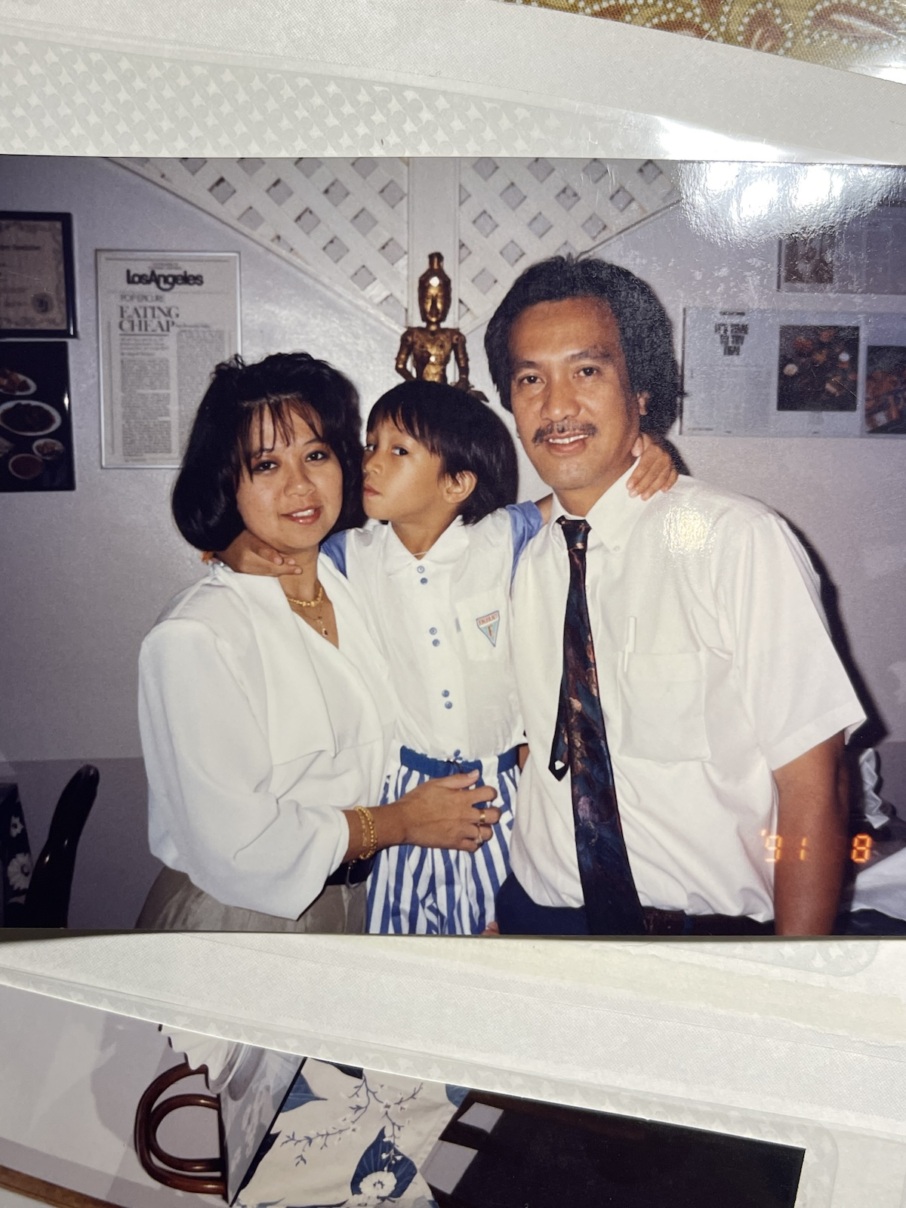

Justin Pichetrungsi didn’t always set out to be a chef. In fact, up until 2019, he was an art director for Walt Disney’s Imagineering department. But the restaurant where he is now the chef and owner — Anajak Thai in Sherman Oaks, Calif. — has always been a part of his life.

Originally opened in 1981 by his father, Rick, Anajak Thai was always a beloved neighborhood Thai restaurant but in recent years, the restaurant’s reputation has only grown, garnering acclaim for its incredible wine list, its Thai Taco Tuesday events and pop-ups, and its uniquely Californian vision of what it means to be a Thai restaurant.

In June, Pichetrungsi is inviting chef Chintan Pandya and restaurateur Roni Mazumdar from New York’s Unapologetic Foods Group (Dhamaka, Semma, Naks, Adda Indian Canteen, and Masalawala & Sons) to join him in Los Angeles for a two-day event celebrating the intersection of Indian and Thai cuisines.

In anticipation of their collaboration, Resy asked them to interview each other about what it means to be unapologetic, and to cook food from your own heritage. Here’s what they had to say.

[Editor’s Note: The following has been edited for clarity and length.]

Roni Mazumdar: What was your vision behind transforming a family-run restaurant into one of the best restaurants in the country?

Justin Pichetrungsi: No one is taking over their family restaurant and saying, “I’m gonna make this the best restaurant in the country.” Those lists are so subjective. I never set out to really win any awards.

For me, it was putting in ideas I was really passionate about. I don’t like to answer to anyone, even my parents, with the ideas. So, it was a process of finding myself and that creative process of cooking and creative process of running the restaurant that I also applied to my artistic life. It took me time to realize it’s something you can apply to a restaurant life, too. There’s creativity in every single crevice of the restaurant in order to run it, all the way down to your systems and the garnish on the plates. It’s like a film: Every little decision, from the props to even the caterer makes a difference in how the impact of the whole thing is. With that being said, it took a little bit of time to get my footing and get my confidence there. That’s sort of how it went down.

I am a long-term planner now, but back then it was about, day to day, making these small improvements. This concept of kaizen is very applicable, because those small improvements every day add up to a whole. That’s the same with the food.

Chintan Pandya: What was some of the advice or a secret mantra your family gave you as you took over the restaurant?

Pichetrungsi: You know, my mom is very conservative in the way things are done. My dad is very accepting of new ways. I guess I’m not afraid to get into it with my folks, you know? If you look at the menu, it’s really an homage to my father’s menu. Much of it is an adaptation of his menu, so I kind of look at the food and I never try to stray away too much from the balance of flavors that my father has established in the food, except for having changed the sourcing quite a bit and tweaking the way we make things and, of course, all the new dishes. There’s something about the trial and error my father made in the kitchen with this food that is something to be trusted. I wanted to change so many things back in the day.

For example, the soy sauce bottle placement on the line — he always had it in a weird spot, and I thought it was so inconvenient to reach for this bottle of soy sauce and he said, “Well, you change it.” And I changed the placement and as the night went on, I realized this was a terrible spot for this. And I ended up putting it back where dad put it. We eventually found a new way to do it, but back then, I really had to trust in the process and trust in my father’s recipes because there was a way that worked inside that space. When I eventually accepted that, that was when I started to actually learn.

Pandya: Why didn’t you create a modern Thai place but instead decided to keep the soul rustic?

Pichetrungsi: I like old things. The real thesis of the restaurant is you can teach an old dog new tricks. I see the charm in it. I wanted a place with a touch of history. It also doesn’t serve the story to be “new.” Some directors build elaborate sets and paint the grass green, but other directors shoot a movie in a place with physiognomy, and there’s a character in the place. I didn’t see it before, but there is a character in the place. The food just smells better in an old place, I guess.

Mazumdar: Why did you choose to become a chef who cooked food from his own heritage?

Pichetrungsi: Thai cuisine is very deep. I’ll never finish the cuisine. I’ll never finish understanding it. There are so many micro-cuisines within Thailand that people just don’t know so much about that I am still learning about. The cuisine moves at lightspeed; trends move on and out so quickly, they’re absorbed and spat out and turned into traditions before you even realize it was a trend, you know?

Here in America, the Thai diaspora cooking moves at a seemingly snail’s pace. It’s seen as this kind of etched-in-stone thing as are all cuisines that are diaspora cuisines in America. No one wants innovative Thai food, and no one wants elevated Thai food. I hate that. I didn’t want to elevate it up or down. We’ve done a tasting menu. What we’re doing is just a contribution to the cuisine, not to say it’s better or worse, or whatever it is. That’s my take — taking that cuisine across a giant body of water and taking it to this land, and it getting reinterpreted with produce and different ingredients, and people, and the audience just appreciating it.

How you know L.A. Thai food to be — whether or not you like to hear this — is a bit of a caricature of itself. And I’m OK with that because it’s fucking delicious. It is. I see the sort of regional variances among L.A. Thai food and New York Thai food and even San Francisco Thai food … no one talks about this, by the way. But when you get into it, we’re all putting it through a lens in a way; we’re just putting it through another lens or several lenses rather.

I love my folks, and I love the restaurant so much. All my ideas were really about what I wanted to do here. Now, via these collabs, I’ve cooked French food at a French restaurant, Pasjoli. I’ve cooked Korean food at Atoboy. I got to experience how Italian, Korean, and French kitchens are run. We’re all the same in the sense that we’re just trying to make something delicious through the cuisines that we are borrowing.

What we’re doing is just a contribution to the cuisine, not to say it’s better or worse, or whatever it is.— Justin Pichetrungsi

Pichetrungsi: Do you feel a level of responsibility to Indian cuisine? Do you think we as chefs have that responsibility for our own cuisines? And if yes, do we have to contribute? Do we have to show innovation? Or do we have to educate the public? Or isn’t it easier to just phone it in sometimes?

Mazumdar: We get one shot of living the life that we do, and we sincerely believe we should live a life of intent and purpose. In the end, it’s about sharing what we really want to with the world without the fear of any judgment. In that thought process, there is no option to phone it in.

Pandya: How can the restaurant industry change itself in some ways to help people better understand cuisines like ours?

Pichetrungsi: I mean, I think it’s to eventually get to a point where we develop the confidence to not change, but I think that’s a complicated question because you have to spend time with the guests. You’ve got to explain it to the guests at the table. And I think the thing about Thai cuisine is that, in my mind, it’s always been equal parts comfort and adventure; it’s equally comforting as it is extremely adventurous and if you want to be extremely adventurous, you can. You can have the spiciest food, and you can be eating insects. Then you can eat raw pork blood and rice, roaches and wasps with the eggs attached to their abdomens. And you can eat the craziest fermented stuff that you’ve ever eaten. Or you could eat pad kra pow and pad Thai. And it’s all part of it.

And so I think, cuisines in general, always find what is the most comforting as an entry point for audiences. And it’ll start as a kind of spaghetti and meatballs thing. And then eventually, as time moves forward, you’ll learn, oh, meatballs are served over here like this. And it’s not spaghetti anymore, and it’s not super saucy, but it’s like this now. And so you eventually separate the meatballs from the spaghetti. And eventually, you don’t need to serve wonton soup at a Thai restaurant.

Mazumdar: Why do you think regional or authentic cuisines have not been embraced in the past like they are now?

Pichetrungsi: We’ve been stuck in our spaghetti and meatballs phase, and the thing is that it’s pretty tasty. So, after generations of eating spaghetti and meatballs, it’s hard to be like, “Oh yeah, try this regional handmade twisted pasta with a milky rabbit sauce.” People are like, “What?” And oh yeah, by the way, that whole menu, it’s now written in Italian. You just gotta take the time. It takes generations. Italian food wasn’t always considered part of American food; it was considered the other, and they’ve got about 70 years on us. Thai food has like 30 years on a lot of the other Asian cuisines, and I’m fortunate for that. It’s just because of time.

Justin Pichetrungsi’s Favorite Places to Eat in L.A.

Antico Nuovo: “I like pulling up a counter seat at this place, which is right down the street from us, with a glass of wine and getting a plate of chicken, and it’s awesome.”

Kuya Lord: “Maynard [Llera], the chef, was just nominated for a Beard award this year. The food is delicious and it’s a very casual atmosphere. It’s astounding how casual the atmosphere is, and he’s cooking the most delicious food, and it happens to be Filipino. And he happens to be Filipino, which is cool. I love it.”

Takeda: “I also love sushi. Every now and then I go here. It’s one of the best sushi omakases in the country. Terrific, terrific stuff.”

Kruang Tedd: It’s this Thai bar that has a cover band every night and it’s mostly only Thai people who go there. I’m the least Thai person there by far, and I don’t necessarily go here for the food, but it’s a magical spot. It’s just in a different world, it’s so cool.

Pandya: Do you believe there is still a hierarchy in food that exists in our industry? If so, how do you want to break through those boundaries?

Pichetrungsi: It doesn’t exist so much in L.A., but I’m sure you still feel it in other spots. In L.A., we’ve really shunned the notion of authentic or ethnic or whatever it is, and we try so hard to break down those boundaries. And I think so much of that is because we have terrific diners who go out and appreciate the bounty of it. So for me, I think L.A. doesn’t have that as much, but I don’t know how it is in New York. I suspect the fine-dining influence in New York is very different.

Pichetrungsi: What overlaps do you see between our respective cuisines?

Mazumdar: From ingredients to techniques and flavor profiles, there are huge similarities between our cuisines, but I think each has its own unique fingerprint. The very essence of how a gravy is made and the long hours that go into knowing the balance it needs to have is a universal theme that dates back generations for both of our heritages.

Pichetrungsi: What’s the overlap in the styles and attitudes of our restaurants in terms of the food and in terms of the space?

Mazumdar: We are both approaching the new generation while celebrating our roots, but we are doing it differently than how our elders did it in the past. We are not trying to fit into anyone’s idea of the flavor profiles or vibe; we play dance music loudly while serving dishes that many members of our community have already forgotten.

Pandya: What made you decide that you can have an outstanding wine program at a time when most “ethnic” cuisines have trouble selling high-end wines?

Pichetrungsi: I mean, I love wine. And I love the stories that it tells. I love the people that make it. I love the people that sell it. I love somms. I love the glassware. I love all of it, you know? People are always asking me, “Why do you sell so much wine?” Well, if you don’t like wine, and you’re not obsessed with it, you’re never gonna sell it. I see people that want to do it, but it’s a half-hearted thing. People want to obviously make money from it, but I never was thinking about making money from it. I was just like, “I think wine is delicious with Thai food.” I’m not the first person do that. There’s Night+Market in L.A. with natural wine, and Lotus of Siam in Vegas with their very deep Riesling collection. Try to find a beverage better than wine to drink with Thai food; it’s so good. So, the answer to the question, really, is why would I not sell wine?

Pichetrungsi: What kinds of new combinations and ideas do you think are going to come about from this collaboration?

Mazumdar: It’s very exciting to get into the mind of a chef and learn about new flavor combinations that they come up with from the very same ingredients and technique. We see that as a whole world of new knowledge that we want to learn about.

Pandya: What inspires you and how do you apply that in your cooking?

Pichetrungsi: I mean, cooking is like painting, in the sense that you have these raw materials and I think there’s a way with how things come out — they have to feel hot, and delicious, and spontaneous. The food has to feel spontaneous. It’s hard to explain to a bunch of cooks who want things to be consistent. The way things are presented, it has to be a little je-ne-sais-quoi in the way that dishes are plated. And I’m a very visual artist first, so I notice these things before I notice other things. It’s not fancy plating. It’s really not fancy plating at all. It’s just ribs. But it looks good. The plates are just white plates. Noodles gotta look hot and oily. It’s gotta look like an oil painting. The brush is big, and with food, it has to look like there’s energy. That’s something that’s so hard to explain to a cook.

Pichetrungsi: How do you make your biryani so well?

Pandya: Biryani is one of the benchmark dishes of Indian food. When I came to America, it was poorly made, and it made me depressed that the cuisine of India was shown in a wrong way. It motivated me to make the best version of Indian cuisine. When I was learning to cook, I learned about biryani and I learned, layer by layer, the cooking process and how it needs to be done right.

Pichetrungsi: How do you teach people to cook such vibrant and specific food at scale?

Pandya: When you work with people with the right approach and attitude, they are more inclined to learn more things and push harder.

Pichetrungsi: How do you get your staff to embody the attitude and personality and feeling like how you do when you are in the space? With places as personal as Dhamaka and Semma, what’s the realm of training look like?

Mazumdar: We do our best to give people a sense of responsibility and ownership, no matter what the role is. It’s easy to show up to a job and clock in, but it’s a new set of standards when it’s your own place that you stand by every day. We do our best to bring on people who share similar values of hospitality and guide them to be the best version of themselves.

Mazumdar: What do you think being unapologetic means, and what’s the most unapologetic thing you have ever done in your life?

Pichetrungsi: I think being unapologetic is exactly what we’ve been talking about. It’s, in order to get people to see the cuisine as the cuisine, you’ve gotta present it in an unapologetic way. The thing that I’ve done? Well, I mean, in the restaurant, our tasing menu is pretty unapologetic — you can’t really choose what you are getting. Spicy is spicy and it’s an exploration of the deeper parts of the cuisine that I’ve always wanted to do. It’s much less approachable, and a much less democratic way to make those dishes, and so doing the omakase has really taught us to develop our confidence in these new dishes.

Pandya: How do you think food can be better represented in America?

Pichetrungsi: From an operator’s standpoint, I think you just have to stand out about an eighth of an inch. You just have to stand out a tiny bit. You don’t need to change yourself into this fine-dining thing if that’s not who you are. You just gotta find the fun in the cuisine and what’s fun enough to really enjoy it, and to stick out just a little bit.

Pichetrungsi: What’s next for you both? World domination?

Mazumdar: We just want to keep going until the far corners of the country understand our cuisine and culture and we pave the way for the next generation, to no longer relegate certain cuisines as “exotic” or “ethnic.”

Get Your Tickets

This June and July, Unapologetic Foods is touring the country to pull off some of the year’s most exciting collabs with chefs that include Anajak Thai’s Justin Pichetrungsi, Galit’s Zach Engel, and Tiger Fork’s Simon Lam.

Must be 21 years of age or older to consume alcoholic beverages. Please drink responsibly. American Express reserves the right to remove any person for inappropriate behavior including, but not limited to, conduct that is disruptive, abusive, or violent.

Anajak Thai will be hosting Unapologetic Foods in Los Angeles on Tuesday, June 11, for one of its Thai Taco Tuesday events, and on Wednesday, June 12, for an intimate dinner combining the foods and flavors of Thailand and India. Find out more here.

Deanna Ting is Resy’s New York & Philadelphia Editor. Follow her on Instagram and X. Follow Resy, too.