Dhamaka and Its Relentless, Unapologetic, and Very Necessary Pursuit

In the past two years since it opened in February 2021, Dhamaka is the relatively newer New York restaurant I have dined at most. I wouldn’t necessarily call myself a Dhamaka regular, but I like to think I’m close.

I’ve brought everyone to that little corner of Essex Street Market: an ex, best friends, work colleagues, friends of friends, and friends from out of town. I’ve eaten (almost) every dish on the menu, including that highly elusive rabbit. (Sorry, Pete.) At this point, I don’t even need to look at the menu because I can recite it from memory — although, to be fair, it probably helps that I wrote a whole story about the menu when Dhamaka first opened.

So, when I saw the news that Dhamaka’s owners, chef Chintan Pandya and restaurateur Roni Mazumdar, were scrapping their old menu and debuting a new one on April 18, I was initially a bit floored. Like many other New Yorkers, I grieve for the loss of biting into that perfect paplet fry once more. They’re also cutting down the number of seats, and debuting an entirely revamped cocktail and spirits menu.

But the news wasn’t much of a shock to me at all. This is, after all, coming from a restaurant group that calls themselves “unapologetic.” Since they first opened Adda in Queens in 2017, Mazumdar and Pandya have never been ones to shy away from change or taking risks.

Shortly after opening Dhamaka, they closed their popular contemporary Indian hit, Rahi, and converted it into the now Michelin-starred Semma. Last year, they launched fast-casual Rowdy Rooster, which gained fame for its uncompromisingly scorching hot fried chicken. Most recently, they reopened Masalawala in a new space (and borough) as Masalawala & Sons, with a deeply personal menu that reads more like a biography for Mazumdar’s father. Dhamaka itself was a huge risk when it first opened, too, but it was one that ultimately led to Pandya winning the James Beard Award for best chef in New York State last June.

Now that they’ve got this huge platform — a James Beard under their belts, critical acclaim both here in New York and abroad — Pandya and Mazumdar could take it easy, and absolutely no one would blame them for it. After all, restaurant work is hard and grueling, and success is elusive, not to mention in this unpredictable economic landscape. If you’re lucky enough to make something magical not just once but multiple times, why push your luck any further?

But the thing is that they simply can’t not change. It is impossible for them, or their restaurants, to stay the same. After talking with them both, I understand why: It’s got nothing to do with monetary success, or James Beard medals. But it has everything to do with what it means to be an immigrant in America, about defining what it means to achieve the American Dream today, and being both unapologetic and most of all, relentless, in revolutionizing how we all think about Indian food today, and for future generations.

***

Both Pandya and Mazumdar are immigrants, but their respective experiences in America differ from one another. Mazumdar moved to the U.S. as a teenager from Kolkata in 1996, while Mumbai-born-and-raised Pandya moved to America in 2013 as an established chef.

Being an immigrant here in America (or anywhere else for that matter) often means assimilating as a means of survival at every age. If you’re a chef or a restaurateur, that means putting butter chicken on your menu instead of goat testicles, or shying away from anything that might be a little too ethnic, or a little too close to “home.”

But Pandya and Mazumdar aren’t operating that way (although, to be fair there is butter chicken on the menu at Adda — but it’s likely unlike any other one you’ve had before). Unlike many immigrant chefs and restaurant owners before them, they’ve found a freedom here in America. And they’re using it to push forward their goal of sharing their love of their food and their culture with as many people as they possibly can. And doing it on their own terms.

“If we only were doing what people expected, then none of these restaurants would have ever been,” says Mazumdar.

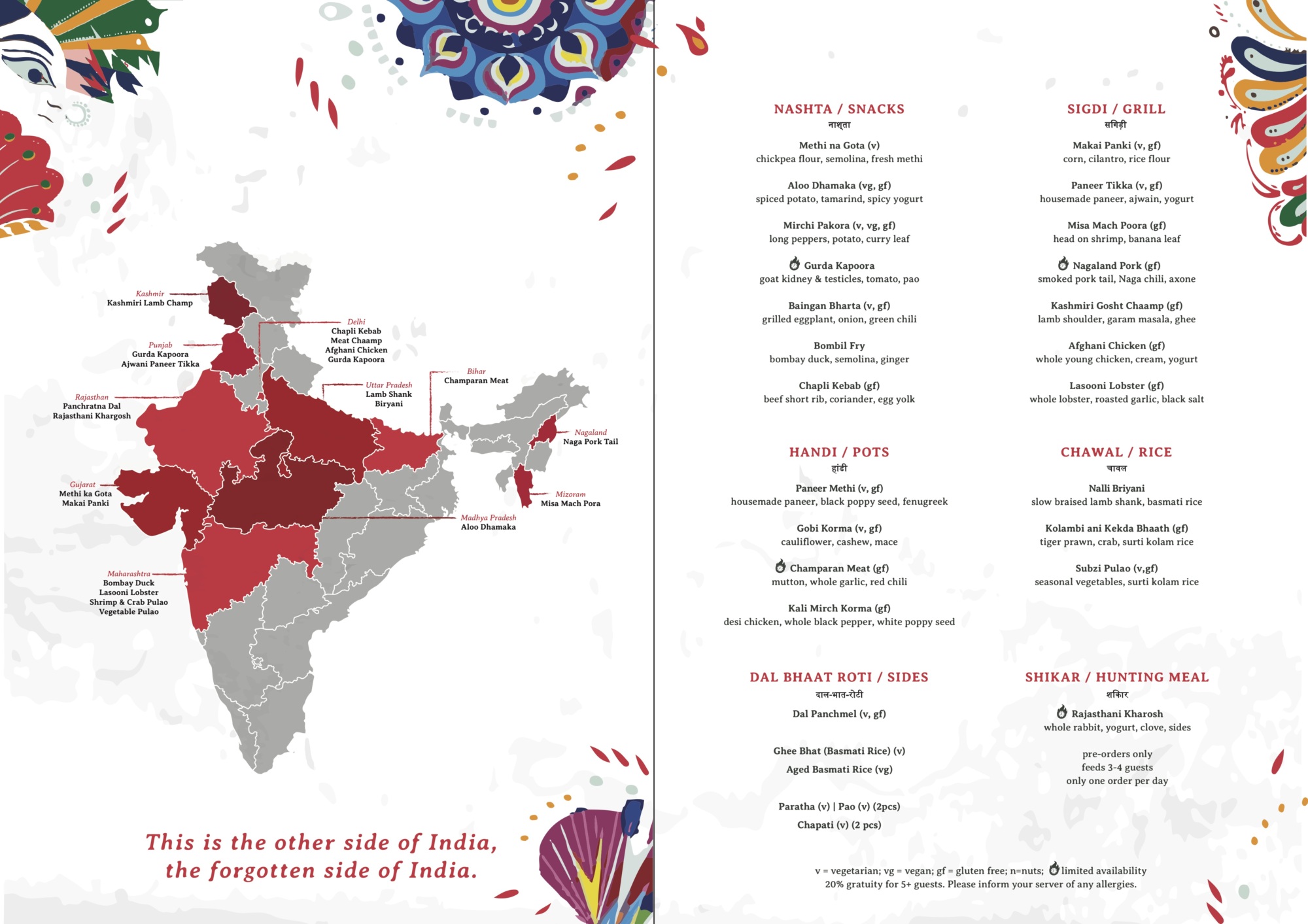

In February, the duo, along with Dhamaka’s chef de cuisine Eric Valdez and general manager Tsepak “Tina” Dolker, traveled to India for a whirlwind three-week tour across the country. It was a homecoming and, in some ways, a powerful reminder why they can’t veer off course from their original mission at Dhamaka — showcasing the “forgotten side of India” — dishes and traditions that aren’t just being erased here in America, but also in India, too.

What struck Mazumdar the most during that recent trip was how “commercial” things had become, and the impact it’s had on the culinary scene: “It’s not as regionally as vibrant as we would like to see,” he says. “There’s so much innovation in India right now, but we’re seeing these dishes, ideas, and people simply disappearing and everything is more factory-based and commercial. The personal touch isn’t there.”

He recalls speaking to an audience of 100 hospitality leaders and asking them if any of them were familiar with the cuisines of Bihar, Orissa, of Meghalaya; fewer than five raised their hands. “That was one of the most alarming things to witness, and an indication of the direct missing links in our own cuisine.”

If we only were doing what people expected, then none of these restaurants would have ever been.— Roni Mazumdar

For Mazumdar, it’s seeing what he loved as a child vanish before his very eyes. For Pandya, it’s not so much about the loss of nostalgia but searching for a way to retain the history of these traditions and dishes; to add context (“the art which goes behind the way it’s done”) to them so they’re more than just something delicious to eat. He acknowledges that even what he’s able to achieve in his own kitchens can’t match the intensity or integrity of what you have (or had) in India. But he’s seen the commercialization take hold, and he wants to make sure we don’t forget where we’ve come from by making these dishes at Dhamaka.

At one point, Mazumdar uses the analogy of being “like an anthropologist, digging through the dirt.” For him and Pandya, you can’t push forward into the future without knowing your past. “There are things that have already been lost, and slowly being covered in the sands of time,” he adds. “But for us there’s this desire to hold on to it, because it also represents us and our own paths and our own childhood.”

In many ways, it’s a reflection of that classic immigrant struggle to retain what you knew of your former home in your new home — except that for them it’s about retaining it in both places, and eventually around the world. It’s something my own grandfather, a Chinese immigrant to America, could never quite achieve with his own restaurants in Kansas, more than half a century ago. For Mazumdar and Pandya, the American Dream isn’t just about having critically acclaimed, profitable restaurants — it’s about sharing their food and culture with everyone, on their terms.

Changing the menu at Dhamaka is an exercise in expanding the exposure that diners like you and me will have to their childhood, and their past. Why stop at 20 dishes when you can push to 200, or 500? In other words, you should expect many more menu changes ahead at Dhamaka in the years to come.

“Two more years later, maybe the name of it will also change” Mazumdar adds. “How do you keep bringing concepts to our cuisines, our heritage and our culture, if you don’t even know where you come from? There’s only a very limited perspective on who we are. I think it’s about expanding that. And that’s the only way I think we’re going to find these inspirations and find these moments that are going to propel us forward.”

Highlights From the New Menu

Dhamaka’s new menu, save for a few exceptions, is entirely new. The biggest change, however, might have to be with the desserts. Where there was only one dessert before — the cheesecake-like chhena poda — there are now three different desserts, one of which even has a tableside presentation. “Chintan 2.0 does more than one dessert now,” Mazumdar jokes. Another welcome addition? A map of India that shows you exactly where each dish originates from, too.

What’s New & Noteworthy:

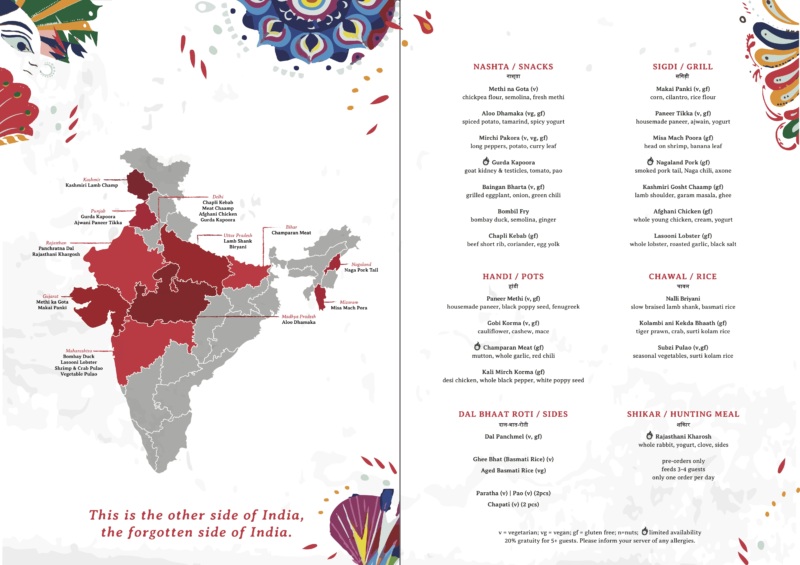

Nashta/Snacks

Methi ka Gota: Mazumdar tasted these fried fenugreek dumplings for the first time recently in Surat, a city in the Western state of Gujarat in India, at a shop specializing in fried foods that were served with an “unbelievable” chutney right on the sidewalk.

Aloo Dhamaka: “It’s like a flavor blast in our mouth that’s a version of a potato chaat that we had in Delhi,” says Pandya.

Mirchi pakora: This vegan dish of peppers stuffed with a spiced potato mixture, battered in chickpea flour, and lightly fried, comes from Jaipur.

Bombil fry: The paplet fry is gone but in its place is this new fried fish dish, made with “Bombay duck” fish — something Pandya grew up with eating in Mumbai.

Sigdi/Grills

Makai Panki: Roughly translated to “corn” and “starch,” this dish, also from Mumbai, consists of a batter with fresh corn and a “secret” flour (different from the tradtional chickpea flour) that’s spread between two banana leaves and then grilled.

Misa Mach Poora: Marinated prawns are grilled inside banana leaves for this dish that originates from Mizoram in Eastern India.

Nagaland Pork: In Northeastern states of India like Nagaland, pork is eaten regularly, and this dish involves a whole pig tail that’s cut up and then smoked or fired in a charcoal fire with Nagaland chiles and spices. “The texture is very interesting,” says Mazumdar.

Kashmiri Gosht Chaamp: Kashmiri lamb shoulder gets marinated in a mixture with a little bit of chickpea flour, and then pan-fried with a “ghee searing” that’s evocative of a confit.

Handi/Pots and Chawal/Rice

Kali Mirch ka Korma: You may have seen korma on Indian restaurant menus before, but you likely haven’t seen this one, made with black pepper and a cashew- and poppyseed-based curry and chicken.

Kolambi ani Kekda Bhaath: Pandya was inspired by the coastal fishing communities of Konkan in the western state of Maharashtra to put this dish, made with short-grain rice (not basmati), on the menu. As before, this pulao will also be served in its own pressure cooker.

Desserts

Fruit chaat: Local seasonal fruits are served tableside with chutney, on a cart.

Rabri: “It’s basically reduced milk, and nothing else,” explains Pandya. Rabri is consumed throughout India, especially in the Northern and Western parts of the country. Pandya is currently searching for “the most high-fat milk” he can get his hands on to make it.

Makhan: Butter that’s freshly churned to order, served with sugar, saffron, and dried nuts with it. “It’s a very simple dessert, and it’s not like a butter you have been exposed to,” Pandya notes.

What’s Staying:

Gurda Kapoora: The intricate sourcing process involving a network of Uber drivers remains for this dish of goat testicles, and Pandya kept it on the menu because it’s sold in such limited quantities: “A lot of people still haven’t experienced that dish yet. We want people to experience it before we take it off the menu.”

Paneer Methi and Paneer Tikka: “Someone would shoot us if we took these out,” says Pandya.

Champaran meat: “I think if there was one dish that I think defines the entire vision of Dhamaka, I think it’s the Champaran meat, because of the region [Champaran in the eastern Indian state of Bihar], and because of how it’s cooked,” says Mazumdar.

Rajashtani Khargosh: The elusive rabbit dish remains so, but at least there’s still time to try it out if you haven’t yet done so.

Dhamaka is open Tuesdays through Sundays from 5 to 10 p.m.

The One Who Keeps the Book New York

How to Get Into New York’s Dhamaka

When Dhamaka first opened in the Essex Street Market in March 2021, the spot’s sister restaurants, Adda and Rahi (now…

Discover More

Stephen Satterfield's Corner Table