Rediscovering a Knife, and a Legacy, at Anajak Thai

A yanagiba, which translates to “willow leaf blade,” is a long, slender knife from Sakai, Japan, prized by sushi chefs for its seafood-handling precision. With its narrow build and graceful single-bevel blade, yanagiba knives skin whole fish and sing through sashimi, leaving little cellular damage to the meat. Constructed from high-grade carbon steel, they often command high prices, which is just one of the reasons that chef Justin Pichetrungsi was surprised to find one abandoned in the back of a broom closet at his Sherman Oaks restaurant, Anajak Thai.

This wasn’t just any knife — the rust-encrusted blade Pichetrungsi came across had once belonged to his father, Rick, a fellow chef and the founder of Anajak. As a young chef, Rick cut his teeth at a sushi restaurant called Miyako in Torrance, where he employed the Masamoto-brand yanagiba for over a decade. Rick eventually abandoned his Japanese knife in favor of a more affordable, serviceable chef’s knife at Anajak. When Justin found the old knife, his immediate question was whether he could salvage the blade.

“It felt like discovering [my father’s] lightsaber,” Pichetrungsi says. “I wanted to know if I could repair it, how much life was left in it, and if I could learn anything through using it.”

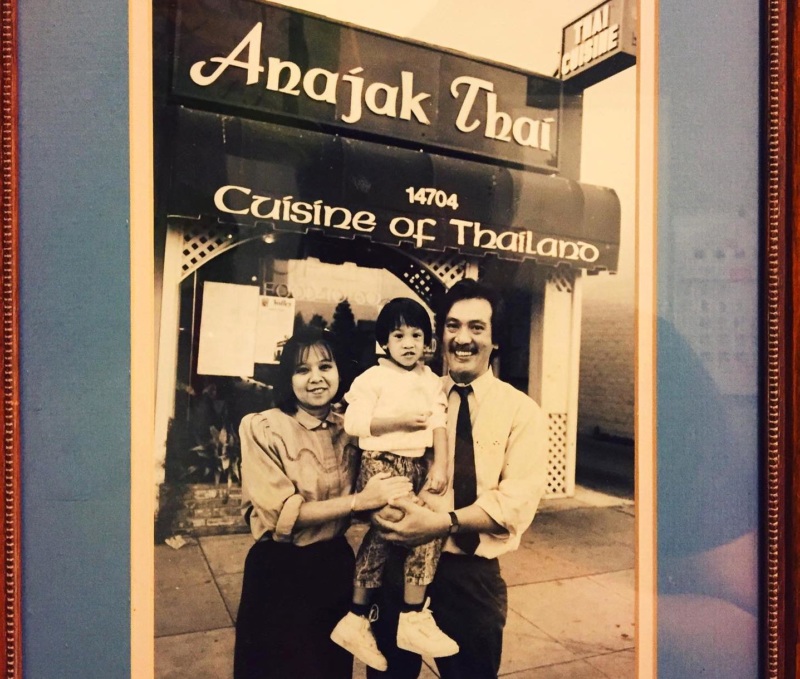

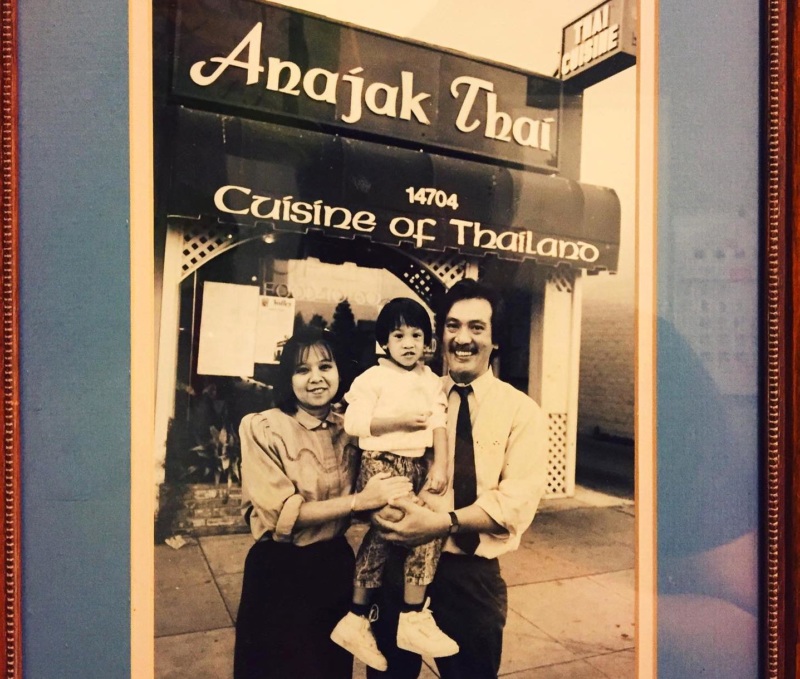

His restoration mission was fueled by a desire to uncover his family legacy, and to honor his father. “Mom thinks I turned my back on Dad and his legacy,” Pichetrungsi wrote on his Instagram. “She makes sure to remind me about it every day.” Bringing the knife back to life would prove that the younger Pichetrungsi cared deeply about continuing what his father started 41 years ago, while acknowledging that he wouldn’t be where he is today (racking up awards left and right) without the foresight, labor, and creativity of his parents.

- At Anajak Thai, a New and Californian Vision of What It Means to Be a Thai Restaurant

- A New Brush With Fame, Yes, But Casa Vega Has Always Been There For Us

- How To Get Into Pijja Palace, Silver Lake’s Indian Sports-Bar Sensation

- The Resy Guide to the 2022 Los Angeles Michelin Guide Winners

- How Spago Changed Everything

The yanagiba was not protected by a conventional saya, the Japanese knife sheath that protects blades from breakage, nicks and rust; instead, it had been hastily wrapped in cardboard. Tiny nicks flecked the knife across its length, and rust permeated its back side. Needless to say, being neglected in a damp broom closet for decades had taken its toll.

Given the extent of the damage, Pichetrungsi wasn’t sure how much could be done. So, he took it to someone who would: Jon Broida, owner of Japanese Knife Imports, a knife sharpening store in Beverly Hills. “We’ve bought many knives there and brought our cooks in to shop from Jon,” Pichetrungsi says. “He’s an amazing guy, and a total nerd with knives.” The two pondered over whether — and to what condition — they could restore it. The rust was extensive, but the signature concave shape on the back side was still intact. “Restored properly, you probably still have some time on this knife,” Broida said.

Limited on time, Broida made a proposal: he would do the major work, if Pichetrungsi would finish sharpening the knife on his own. Pichetrungsi agreed.

Broida knows that many of his restoration projects are undertaken for sentimental reasons. “A knife is a well-made thing with a specific task that can improve upon the quality of work when used effectively, but more than anything else, they represent memories — moments in time and space,” he says. Pichetrungsi’s knife held more emotional than physical value, Broida says, calling the yanagiba “the Toyota Camry of knives at that time — high-quality, but ubiquitous in many kitchens.”

Masamoto knives, forged from high-grade carbon steel, are easier to sharpen when nicely polished. Broida began by removing the handle, straightening the blade, and cleaning the rust and orange-brown spotting from the hira, the upper section of the blade.

“It was a lot of work, because it was bent and twisted and deeply rusted, and there were sharpening and profile issues with it,” Broida says. “But it seemed important to do it and it was a very compelling story — who wouldn’t want to be a part of something like that?”

The knife, Broida felt, represented more than just a physical object: It reflected the tension between Pichetrungsi and his parents over what each generation desires and expects for Anajak. “You can see clearly that Justin refuses to conform to what someone else wants, and yearns for acceptance of what he’s doing and wants to achieve,” he says.

In a matter of hours, Broida had re-sanded and re-worked the knife into a viable kitchen tool that connects Pichetrungsi to his family. Today, the chef uses his new-old knife regularly. “I’m very attached to it now,” he says. “It’s a beautiful visual metaphor, representative of the fact that I want to try as best as I can to pay homage to what my family built in this restaurant. At the same time, you cannot preserve something without changing it.”

After Pichetrungsi told his father, who retired from Anajak in 2019 following a stroke, about the knife restoration, Rick’s response shocked him. “I think I may have another one in that broom closet somewhere,” he said. Pichetrungsi may find it someday, or he may decide to leave it for the next generation to discover and restore.

Dakota Kim is a writer, editor and recovering restaurant owner living in Los Angeles. Her stories have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Food & Wine, Travel + Leisure, Civil Eats, Food52, and many other publications. Follow her on Twitter. Follow Resy, too.