How Spago Changed Everything

Spago opened on a chilly evening in January 1982.

The first night, 21 Rolls-Royces jammed into the restaurant’s tiny parking lot off the Sunset Strip. The dining room — painted pale pink and beige with a wood beam ceiling and bursts of flowers throughout — held 40 tables, and all were packed. At one point the crush of diners became so intense cooks began handing out wood-fired pizzas to the crowds gathered around the open kitchen, who had grown ravenous after rounds of free Champagne.

Almost immediately, tables were booked out weeks ahead, then months. Three reservation lines (plus one unlisted VIP number) rang nonstop. Spago. Can you hold? The restaurant turned a $20,000 profit in its first month of operation.

“There was never anything like it then, and there’s never been anything like it since,” says Jannis Swerman, a restaurant publicist who was assistant maitre d’ during Spago’s first nine years.

The unprecedented success of Spago caught everyone off guard — perhaps most of all its then-32-year-old chef and owner, Wolfgang Puck.

“We refuse about 300 reservations a day,” an exhausted Puck told the Los Angeles Times in October of 1982. “I thought it would be maybe two or three months of this and then it would normal out. But it just gets more and more.”

The reign of Spago turned out to not be a matter of months, or even years, but decades. The storied celebrity haunt, which relocated from its perch in West Hollywood to Beverly Hills in 1997, celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, an accomplishment made more impressive by the notoriously fickle nature of both Hollywood and the dining public in general.

It can be easy, in hindsight, to overemphasize the role of a single event in defining broader cultural shifts. History is rarely so cause-and-effect. But that’s not the case with Spago. Tease out the fabric of L.A.’s dining culture, and arguably modern American dining as it exists today, and it’s hard not to find each thread — the wood-burning oven, the open kitchen, the exaltation of local ingredients and vivid flavors, the informal-yet-focused service — traces back in some way to the Little Bistro That Could. Whether we realize it or not, four decades later, we‘re all still eating in the shadow of Spago.

▪️

It’s practically impossible to consider the arc of the original Spago without linking it to the meteoric rise of Puck, the first and arguably most famous celebrity chef of the mass media era, a chef whose pearly grin has, over the years, graced everything from soup cans and frozen pizzas to Home Shopping Network specials.

But before the global empire — there are now 104 Puck-affiliated properties across the world, including Spago locations in Istanbul, Singapore, Maui, Budapest, and Vegas — the flagship on Horn Avenue was a distinctly Los Angeles phenomenon, an often-imitated, never-duplicated concept that would permanently alter the city’s dining landscape.

Though not quite comparable to the effects of a global pandemic, a slogging recession (see: the Volcker Shock) hung over the restaurant industry in the early 1980s. Many of Hollywood’s established celebrity spots had grown sclerotic. The famous dish at Chasen’s — a favorite of the Reagans — was a bowl of chili; a signature at Sinatra-beloved Scandia was the “Viking Sword”: a smoked pork chop, whole chateaubriand, and turkey breast impaled and smothered in béarnaise. Le Dome, a clubbish music industry hangout better known for elbow-rubbing opportunities than its straightforward Continental fare, was about as lively as things got.

Puck, then chef and partner at Melrose hot spot Ma Maison, was a bolt of energy. A few short years after relocating to L.A., he had gained a following among stars like Burt Reynolds and Elizabeth Taylor for his progressive take on nouvelle cuisine. But the Austrian-born, French-trained wunderkind wanted to open his own concept: something more casual, with pizza and pasta. After a falling out with Ma Maison owner Patrick Terrail, Puck struck out on his own.

The menu has changed, the chefs have changed, but the vision has always been the same.— Wolfgang Puck

The restaurant was originally to be called Mt. Vesuvio, but famed disco producer Giorgio Moroder suggested the name Spago instead, an Italian word meaning string that was slang for pasta.

Despite Puck’s popularity among the Hollywood set, most of the 20 or so investors in Spago were well-to-do professionals: dentists, doctors, and stockbrokers from the Westside or the Valley who had witnessed Puck’s finesse at Ma Maison. The seed money they pooled was enough to lease a worn two-story building along the Sunset Strip that was previously a Russian-Armenian restaurant; the total cost of opening Spago was around $700,000 ($2 million in today’s dollars), according to the Los Angeles Times.

Barbara Lazaroff, then a 29-year-old theatrical designer and interior decorator, served as Puck’s business partner and muse. The couple, who later married and eventually divorced, had met at a local disco a few years earlier. Lazaroff was fiery and flamboyant, a fast-talking counterpoint to Puck’s easygoing, boyish charm. She famously wore a satin jacket embroidered with “I’m not Wolfgang Puck’s girlfriend; he’s my boyfriend.”

It was Lazaroff who largely dictated the look of Spago, from its iconic wire-basket patio chairs to the bleached wood counters. She also convinced a skeptical Puck that an open kitchen — unheard of at the time — was worth ripping down a load-bearing wall, all so guests could spy the chef plating arugula salad or flipping squabs on the grill.

“It was revolutionary because it created a completely different experience,” says Puck, now 72. “Suddenly I’m on a stage, you know, and when people walked in it grabbed their attention. They would come up and ask me what was good to eat that day.”

With the full dining room on display, the design ensured that the kitchen crew remained at their most presentable: no messy aprons, no cursing over burnt sauces. (As Valentino chef Piero Salvaggio once asked Puck incredulously: Where does the chef go to explode?) Yet what seemed like an avant-garde affect early on quickly became the standard for new restaurants around town. The exhibition-style kitchen would become so renowned that high-end real estate listings in L.A. would often advertise a “Spago kitchen” among a home’s amenities.

Puck’s first culinary hire at Spago was Mark Peel, a lanky 27-year-old Chez Panisse alum who had trained at Ma Maison and was now turning heads at Santa Monica trendsetter Michael’s. Peel in turn recruited Nancy Silverton, Michael’s pastry chef, who had garnered early acclaim for her sophisticated desserts. With a staff in place, first on the checklist for Puck’s custom kitchen was a wide wood-burning brick oven, much like the ones he’d cooked with in Europe.

While at Chez Panisse, Peel had jotted down the phone number of the German bricklayer who had constructed the Berkeley restaurant’s oven, so Puck rang him up and ordered one built to his own specs — large enough to fit a whole baby lamb. Once installed, at considerable cost, it was Lazaroff who finally persuaded a stubborn fire marshall to get it approved — another first for L.A.

A short menu, hand-illustrated by Puck, promised “California Cuisine.” Although Spago wasn’t the first restaurant to cook in that style — Michael’s had built its reputation on bright, rustic seasonal fare a full two years prior — it codified and defined a movement that was still in its infancy: “local ingredients, emphasis on the grill, vinaigrettes instead of sauces, uncluttered plates,” wrote the critic Ruth Reichl, the Virgil of this new California cuisine, in a 1992 retrospective for the Los Angeles Times.

As much as anything, Spago galvanized the sense of California cuisine as a cuisine — a perspective that was distinct from what had come before, and recognizable beyond the coast, thanks in part to Puck’s growing star power.

Compared to his contemporaries, however, Puck was more open to incorporating a wide range of culinary influences, which would separate Spago from the purist, ingredients-are-all-that-matters sensibility in the Bay. There were no French words on the menu, a noticeable departure from Ma Maison (and most fine-dining spots at the time). An appetizer of avocado and daikon sprouts with marinated raw tuna — Puck sourced the fish himself from a Japanese fishmonger downtown — utilized the knife skills of garde-manger (and future Chinois chef) Kazuto Matsusaka, while a pizza with smoked lamb and eggplant was prepared by Ed LaDou, a dough prodigy who went on to develop the menu for California Pizza Kitchen. Silverton’s desserts spanned from a delicate mille-feuille with raspberries, to apple pie with caramel ice cream. It was food that emphasized quality and simplicity, but wasn’t dogmatic. Instead, it was freewheeling and fun.

“When the Chez Panisse crowd started out, the influence [from Europe] had to be learned, but for someone like Wolfgang it had to be unlearned,” says Patric Kuh, the former restaurant critic for Los Angeles magazine and author of “The Last Days of Haute Cuisine.” “The food at Spago was like loosening a tie.”

Even if angel hair pasta with goat cheese and broccoli no longer has the pizzazz it did then, a surprising number of early Spago dishes wouldn’t be out of place on a menu in 2022: grilled sweetbreads with vinegar butter and lamb’s lettuce; dill smoked salmon with caviar cream; duck breast “Chinese-style” with shiitake mushrooms and scallions. And Puck’s vision of “upscale casual” dining meant that no pizza or pasta would cost more than $10 (equivalent to $28 today), a bargain compared to fine-dining restaurants that sold entrees for nearly twice as much.

Not that the restaurant’s clientele were watching prices that closely. Although Puck had wanted a place that was more egalitarian than his last restaurant, the Hollywood elite who had frequented Ma Maison promptly followed the chef to West Hollywood. (A notable exception was Orson Welles, whose legendary girth led him to swear off climbing Spago’s steep stairs).

Serving a few hundred guests a night, seven nights a week, Spago emerged as the laid-back SoCal equivalent of New York’s Studio 54: a clubhouse for the chic and sexy, indulgent but without pretense. That reputation was cemented further when super-agent Irving “Swifty” Lazar chose the restaurant as the site of his revered annual Oscar-night dinner party. Limos, paparazzi, and a glamorous clientele were constant. Elton John and Rod Stewart played concerts in the parking lot. As Puck liked to quip, “everyone from Billy Idol to Billy Wilder” ate at Spago.

How did Spago cultivate such a rare strain of loyalty in Hollywood? Namely because both Puck and Lazaroff had a knack for making celebrities feel taken care of without fawning over them, a quality exemplified by one of the restaurant’s most famous creations, the so-called “Jewish pizza.” The story goes that Puck invented the dish — a crackling pizza crust spread with dill crème fraîche, smoked salmon, and a pop of caviar — for legendary actress Joan Collins as an à la minute swap when the kitchen ran out of brioche.

The smoked salmon pizza morphed into a kind of shorthand for the restaurant’s generous hospitality, which often entailed complimentary dishes sent to tables whose cocktails came out a few minutes late, or who were celebrating a special occasion.

“Fred de Cordova, the producer for The Tonight Show, used to come up to me and say ‘Wolf, all I want is chicken soup,’” recalls Puck. “We didn’t have chicken soup on the menu, so I said, bring me two chicken legs and some stock. We’ll make chicken soup.”

There were more eccentric examples, too, like how the waitstaff knew to stock pints of Häagen-Dazs for Prince Omar, a mysterious Saudi royal known to arrive in an electric blue leather suit and hand out $20 bills to any staff he passed. Or that actress Suzanne Pleshette would bring in her own spaghetti sauce for the kitchen to reheat, and that real estate developer and philanthropist Mark Taper preferred his broccoli puréed to the consistency of baby food. “All you have to do to be successful,” Puck once told Reichl, “is give people what they want to eat.”

Modifications, in other words, were never politely declined. It was that “say yes” approach to hospitality that Danny Meyer later credited as an influence when he opened New York’s Union Square Café in 1985.

Despite the air of nonchalance, Puck and Lazaroff worked purposefully to cultivate a certain scene: waitstaff wore striped pink shirts and bistro aprons rather than jackets and ties, and were encouraged to be gregarious with guests.

“I didn’t care if they knew how to filet a fish or slice a duck, because I could teach that. The most important thing was that they knew how to smile and be friendly,” says Puck. “Some were French, some American, but they all wanted to work and have a good time.”

Naturally, the frenetic atmosphere was also conducive to certain bouts of ‘80s excess, whether it was the bathrooms that seemed to be constantly occupied or the intoxicated starlet who threw a full-blown tantrum when she wasn’t offered her preferred seat near the window.

“It was a time when people would wrap a gram of cocaine in a $20 and try to tip the hostesses for a table,” says Carl Gottlieb, an actor and screenwriter (he co-wrote Jaws) who found himself on Spago’s A-list after colleagues Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson waved to him at dinner and a sharp-eyed hostess jotted a note in the phonebook-thick reservation ledger. “I never had to wait long for a table after that,” says Gottlieb, now 84.

A small scandal ensued when the restaurant’s opening maitre d’ — fine-dining veteran Henri Labadie, whom Jannis Swerman described as “the guy that the old school maitre d’ character in movies was based on” — was fired by Puck for accepting bribes in exchange for tables, or at least doing so in a way that was too obvious. He was promptly replaced by Belgian-born Bernard Erpicum, a sommelier who became the face at the reservation stand for more than a decade.

“He made a lot of money selling tables, too,” laughs Puck. “I remember a few years later I bought a house for $150,000 and he bought one for $300,000.”

With help from Erpicum, Swerman, and newly hired general manager Tom Kaplan (now senior managing partner of the Wolfgang Puck Fine Dining Group), Spago’s chaotic first year — a 1983 New York Times story quipped that even those who loved the restaurant “generally agreed [it had] the worst service in town” — gradually transitioned to a more steady pace of operation. By the time the 1984 Summer Olympics rolled into town, the restaurant was running like a Swiss watch.

Meanwhile, Puck’s influence had begun to catalyze: A year prior, he had opened his groundbreaking Asian fusion restaurant Chinois in Santa Monica, and was becoming known nationally as a television star and tastemaker. Peel and Silverton, then married and with two children, left to pursue their own restaurant. There were more projects for Puck in the coming years, including a short-lived downtown brewery, an Italian concept in San Francisco, and a wildly successful expansion to Vegas. But the original Spago remained the crown jewel.

Then, after 19 years, the unthinkable: Spago had to move. The lease on the Horn Avenue address was expiring, and rather than pay to fix the rusty pipes and sagging foundation, Puck and Lazaroff decided to open a much larger Spago in Beverly Hills. The West Hollywood location would finally close in 2001.

The new Spago was only three miles away, but its success was hardly guaranteed. Crowded window seats overlooking Tower Records had been replaced by wide tables in an airy dining room and a patio shaded by olive trees. It was pleasant and contemporary, sure, but what could replace the electricity of the Sunset Strip? As it turns out, the clientele on Canon Drive didn’t need to be so shocked.

Puck, never one for sentimentality, had read the room shrewdly once again, adapting to a crowd that had matured alongside the restaurant. It was still Spago, still L.A. — just a little more refined. Or as Kuh once put it, “casual with lots of zeros.”

Still, there remains some ambiguity around the matter of whether Spago is still relevant. That question was posed by Los Angeles Times restaurant co-critics Bill Addison and Patricia Escárcega in a pair of 2019 reviews, which chronicled the highs and lows of three lavish meals but mostly avoided firm pronouncements. “Spago will always have its audience,” Addison noted, while admitting his own preference for other “splurges around town.” Escárcega smartly interrogated the significance of Spago among diners who hadn’t witnessed its ecstatic heyday, concluding it had evolved into a “one-size-fits-all special-occasion restaurant” that “lands squarely in the golden mean of upscale dining: modern but not exactly modernist; elegant but not stuffy; stimulating but rarely thrilling.”

In some ways, it can be difficult to assess a restaurant whose essential DNA can be found at nearly every casual fine-dining spot in the city — and is still going strong in its own right. A generation of chefs that came up in Spago kitchens — Michael Cimarusti, Sherry Yard, Govind Armstrong, Evan Funke, Nancy Silverton not least of all — now manage culinary fiefdoms of their own. These days the restaurant is as much a brand, an aesthetic, as it is a physical place. The reality of blazing a trail is that someday it might grow into a six-lane freeway.

But even if Spago of 2022 isn’t the disruptive force it once was, it has spent the last decade doing something equally commendable (and rare): settling into a confident middle-aged groove. Service is polished without feeling hollow, and the waitstaff will crack a cheeky smile if, for example, they mistakenly pour a bottle of vintage riesling far more expensive than what you’d ordered but charge the cheaper price. Reservations, though occasionally difficult, no longer require a bribe.

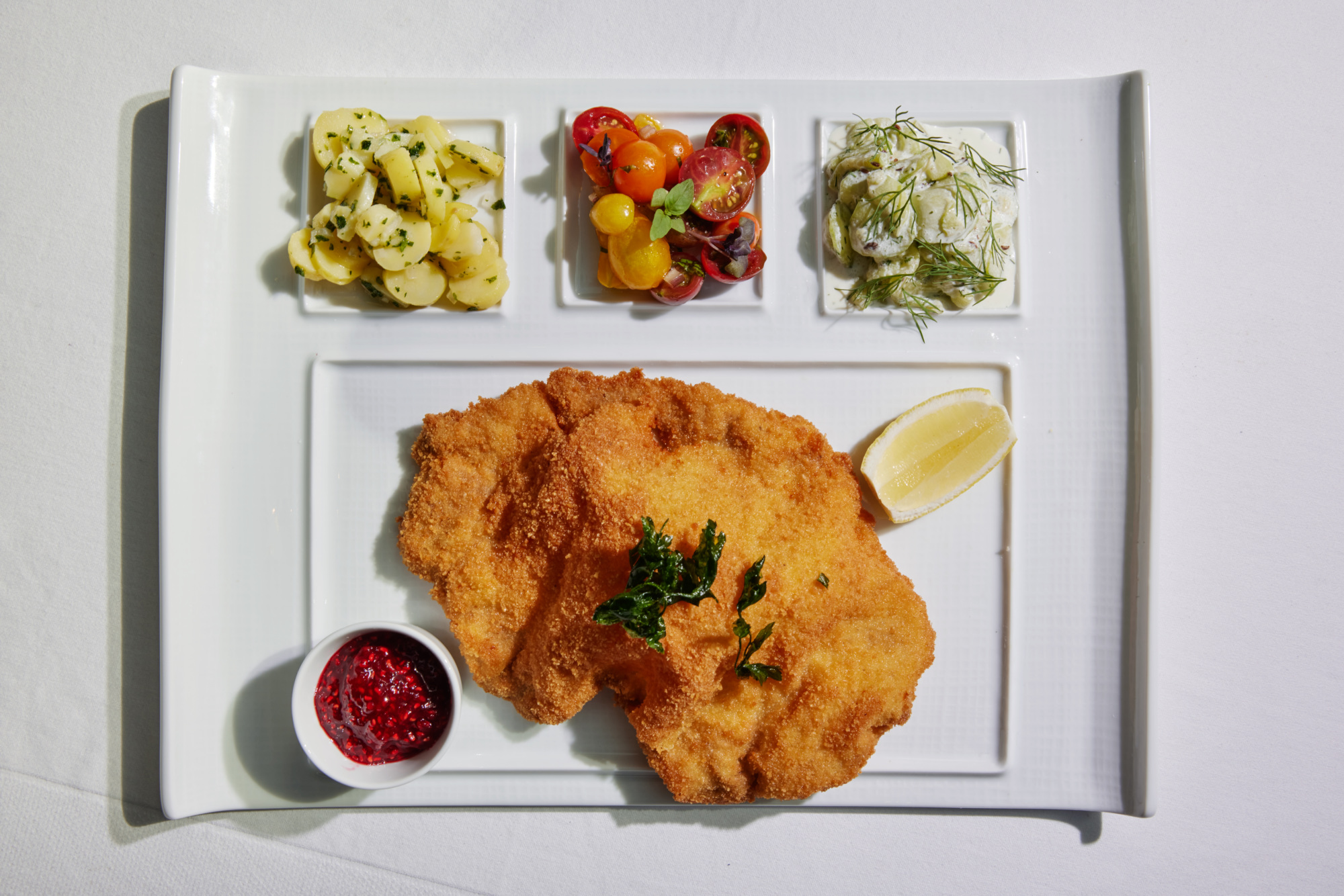

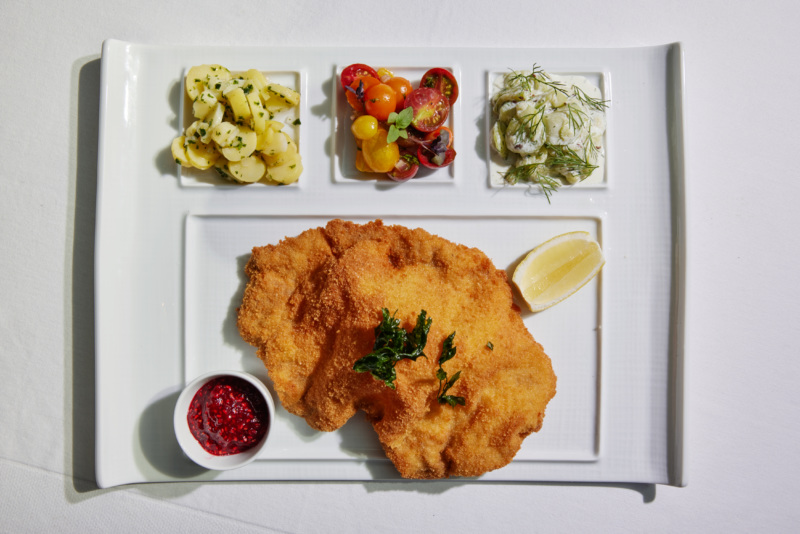

The menu, now overseen by executive chef Ari Rosenson (whose first job was at Spago West Hollywood in his teens), has evolved, too, without losing its refined California sheen. Guests are as likely to be charmed by a bright winter salad of Cara Cara oranges, endive, and niçoise olives as they are the rye tart crowned with Kaluga caviar. And while classics such as the crispy wienerschnitzel and the tuna tartare cones remain on the menu — nostalgically preserved as regulars might insist — the most rewarding parts of a meal are usually when the kitchen finds fresh ways of channeling the sensibility Puck perfected years prior, whether in seared duck breast with quince and roasted turnips, or plump agnolotti filed with celery root and mascarpone.

“We have a good mixture of innovation and tradition, I think. That is what kept us going for so many years without missing a beat,” says Puck. “The menu has changed, the chefs have changed, but the vision has always been the same.”

Perhaps that’s why Spago has outlasted so many of its contemporaries — it understands (and wholeheartedly embraces) its philosophy without getting stuck in time. At Horses, a buzzy Cal-French bistro that chefs Liz Johnson and Will Aghajanian opened last year on Sunset Boulevard, a crackery sheet of lavash topped with smoked salmon not-so-subtly nods to the pizza that defined Puck’s career. It’s a signal of ambition but also admiration. Even the hottest new spot in Hollywood knows to pay homage to its forebear, the restaurant that changed everything.

Garrett Snyder is an L.A.-based writer and editor who was previously a staff reporter at the Los Angeles Times. He is also the co-author of three cookbooks, including a New York Times bestseller. Follow him on Instagram. While you’re at it, follow Resy, too.