Welcome to Ask Resy, in which Team Resy (and friends!) answer your most burning questions on all topics food and dining. For this inaugural edition, we asked you to send us everything you wanted to know about sushi omakase.

Here to answer your questions: a panel of Resy experts, consisting of five acclaimed sushi chefs from across the country, helming everything from Michelin-starred to speakeasy sushi omakase counters.

Read on and stay tuned for a next edition of Ask Resy, coming soon.

What are the biggest misconceptions diners have about sushi omakase?

Sangtae Park of Omakase Yume in Chicago: That it’s all about the fish. The quality and ratio of the rice is just as important as the quality of fish.

Jesse Ito of Royal Sushi Omakase in Philadelphia: That fresh is best. Aging fish can bring out delicious flavor nuances and change the texture of what would have been a chewy bite. Uni can taste terrible, but a good sushi chef will be very particular about the sourcing and taste each shipment before serving it, because the flavor varies box to box. Some mackerels are oilier than others, but when correctly salt cured and washed in vinegar, they are some of the best bites of sushi, period.

Tetsuaki Otomo of Sushi Yasuda in New York: That omakase is a prix-fixe meal where all the diners get the same meal. At Sushi Yasuda, we make omakase based on each diner’s individual tastes and appetite, and our feeling about what would be a special meal based on the many kinds of fish and other ingredients we have.

Niki Vongthong of Hidden Omakase in Houston: That sushi is only raw. It can be made with cooked fish and vegetables. And that sushi is expensive; you can find it at reasonable prices.

J. Trent Harris of Mujō in Atlanta: That gari (pickled ginger) is a condiment. Please don’t top your nigiri with the gari!

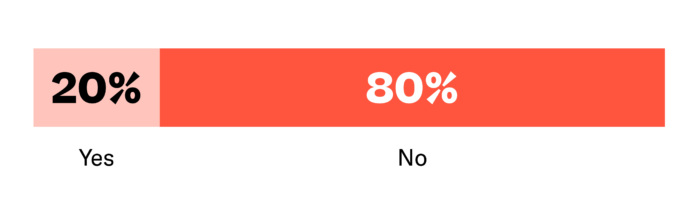

Could you accommodate a vegetarian diner with enough advance notice?

Pro tip: “If you’re looking for a vegetarian Japanese experience, seek out a shojin ryori restaurant!” says Harris.

Why are omakase prices often so expensive in America?

Jesse Ito: The cost to do an omakase is huge. Wasabi root from Japan is around $200/lb. Fish costs range between $18/lb. to $120/lb. including the head, organs, and bones. Factor in labor costs and intimate limited seating, and it becomes very expensive to do right.

J. Trent Harris: For us, the ingredients are very expensive and there is a lot of labor involved. When you think about the fact that you’re paying for a fisherman in Japan to catch the fish, bring it to the market, have our brokers purchase that fish, and ship it across the globe to us, then have a chef prepare a meal and hand it to you, it really isn’t as expensive as it should be.

Sangtae Park: The fish used in omakase is often of the highest quality, comes from Japan directly, and is highly dependent on the season. In addition, there is a lot of work, care, and labor to produce a piece of sushi, from the various methods of preparing the fish to the garnishing components. Many of the complementary ingredients, such as the seasonings, are from artisanal producers.

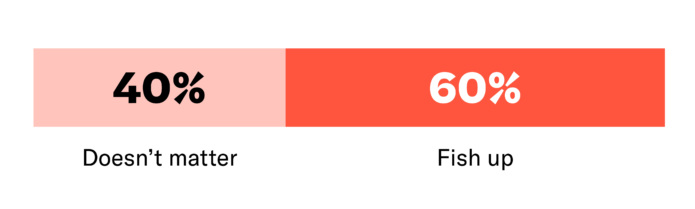

What’s the proper way to eat nigiri: fish up or down?

Pro tip: Always eating the nigiri in one bite is the most important, say Harris, Ito, and Otomo.

How do you judge a quality sushi omakase experience?

J. Trent Harris: The rice, or shari, is the most important thing. If the rice isn’t good, nothing else matters. After that, you can really tell a chef’s skill by the quality of their kohada (gizzard shad) preparation.

Niki Vongthong: I always order the kohada first if I see it on the menu — for me, the way a sushi chef handles kohada tells me if it’s a good sushi restaurant. Gizzard shad is easy to over/under cure or over/under pickle.

Jesse Ito: The sushi rice — temperature, how it’s molded, the taste, the texture. Any chef can buy expensive fish from Japan and make sushi. But it takes skill and technique to make good sushi rice, and experience to mold beautiful nigiri. This cannot be bought.

Sangtae Park: I look for the quality, taste, and technique of the rice. The rice needs to stay intact when picked up, but as soon as you take a bite, it should easily break apart within the mouth. I also look for the fish-to-rice ratio and balance: It’s very important to not have too much or too little rice, as the flavor and texture of each should be complementary. The processing of each piece of fish may not be evident to many, but it takes a lot of skill in terms of salting, aging, cutting, and garnishing each piece of nigiri.

Should you dip your nigiri in more soy sauce?

Pro tip: If you were to dip the nigiri in more soy sauce, it wouldn’t taste as the chef intended it to be, says Park. “Every piece of nigiri made by the chef has the perfect ratio of fish to rice, and amount of soy sauce and wasabi.”

What’s your favorite piece of nigiri to eat?

J. Trent Harris: One of my favorite fish is sanma (pike mackerel or pacific saury) when it’s in season in the fall. When it’s super fresh and prepared as nigiri, it’s one of my favorite bites in the world.

Sangtae Park: My favorite is silver-skinned fish, commonly referred to as hikarimono, which includes saba (mackerel), kohada (gizzard shad), iwashi (sardine), and aji (horse mackerel).

Niki Vongthong: Mostly silver-skinned fish, like mackerel, sardine, kohada, etc. I like the stronger pieces.

Tetsuaki Otomo: [Anything from the] family of mackerel.

Jesse Ito: Favorite to eat is mirugai a.k.a. geoduck, a.k.a. giant clam.

And your favorite piece of nigiri to make?

Niki Vongthong: Kohada, which belongs to the herring family. I like fileting it, sprinkling salt, and pickling it. It’s kind of therapeutic for me.

Jesse Ito: Saba. It’s one of the most technical fish to work with. Many diners avoid mackerels because they think it’s fishy. When done properly, it’s one of the best fish to pair with rice, and I love watching diners fall in love with something they thought they’d hate.

Sangtae Park: Shime saba (cured mackerel).

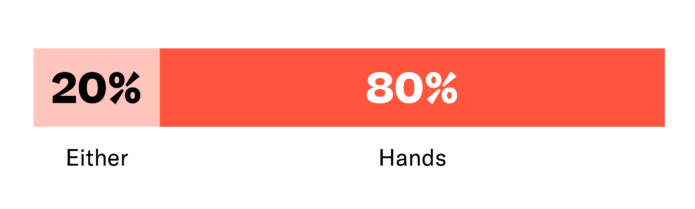

How should you eat sushi: hands or chopsticks?

Pro tip: If you use chopsticks, some sushi chefs may make the rice warmer, so it doesn’t fall apart.

How do you choose a sushi omakase restaurant?

Niki Vongthong: I often choose omakases that have seasonal fish and fish I’ve never heard of or seen before.

Sangtae Park: I look for the variety of fish that they serve, the technique they use to prepare each piece of sushi, and the flavors that each chef can coax out of the ingredients.

Jesse Ito: Reputation. Pictures. I can tell a lot about the place from the way the nigiri is sculpted and the way the rice looks.

J. Trent Harris: Most often it’s based on personal recommendation from another chef or diner I know well. We work a lot, so I don’t get to dine out as often as I’d like!

Is it rude if you don’t finish all of the food?

Pro tips: “If you get full, it’s ok to let the chef know you’re tapping out,” says Harris, “but leaving your sushi on the plate or taking half bites is a little disrespectful to the chef.” Otherwise, Park says to ask the chef for less rice!

How is the order of the nigiri served at your restaurant determined?

Jesse Ito: I think of it like a music playlist or a setlist, but with all bangers. I start out with a statement piece to set the tone with new diners, then go generally light (shellfish and white flesh fish) to heavy flavor (mackerels and tunas), with very dynamic pieces mixed between to keep it interesting.

J. Trent Harris: I prefer to start with lighter, more delicate items in the beginning, then move on to richer, fattier fish, finishing with sweeter neta (sushi toppings) such as ebi (shrimp), hotate (scallops), and uni. We like for the progression to build the way a good wine pairing can.

Sangtae Park: I put a little twist to keep it interesting and give my diners a variety of interesting flavor experiences. I like to start with light white fish, then to richer and fattier fish, back to white fish again that have a richer umami component, and finally back to fish with more flavor.

Tetsuaki Otomo: Depending on the customer’s preferences, I may start with sushi that I know they love. Then I make the order based on how the flavors and textures relate with the many different kinds of fish that we bring in. I might begin with chu-toro (medium fatty tuna), move to milder fish like madai (sea bream), a more oily fish like kanpachi (amberjack), a stronger shiny fish like aji (horse mackerel), a lightly seared nodoguro (black throated sea perch), then to rich toppings like uni, and then a hand roll like negitoro. It depends on many different factors and changes day to day, customer to customer.

Noëmie Carrant is Resy’s senior writer. Follow her on Instagram. Follow Resy on Instagram and Twitter, too.