How Chama Mama Celebrates Georgian Cuisine and Culture, in Five Dishes

In 2019, when Tamara Chubinidze opened the first location of Chama Mama, her irresistible Georgian restaurant in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, storytelling and the sharing of heritage were as important to her as the food.

“Chama Mama is my love letter to Georgia,” she declares. “I came to the U.S. aged 15 with my father in 1996, and ever since I’ve been explaining my homeland to others: our language and culture, our cuisine and winemaking traditions.”

The Republic of Georgia is the utterly singular nation of some four million bordered by Russia, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia. Once part of the Soviet Union it’s been independent since 1991. “But many people here had no idea where Georgia is,” Chubinidze says, laughing. “They’d ask if I was from Atlanta!”

“I always had this idea,” she continues, “of taking people to a magical place where they’d experience Georgian hospitality and our tradition called supra, a feast that can last hours with guests drinking and toasting around a table covered over with dishes.” Until recently there were few such places in New York. “So I told myself, ‘Stop dreaming, Tamara, and open one,’” recalls Chubinidze. Which is how Chama Mama was born.

And the name? Chama means ‘”to eat” and “mama” actually means “father” in Georgian. “But I love how ‘mama’ also conjures up motherly flavors and love,” says Chubinidze.

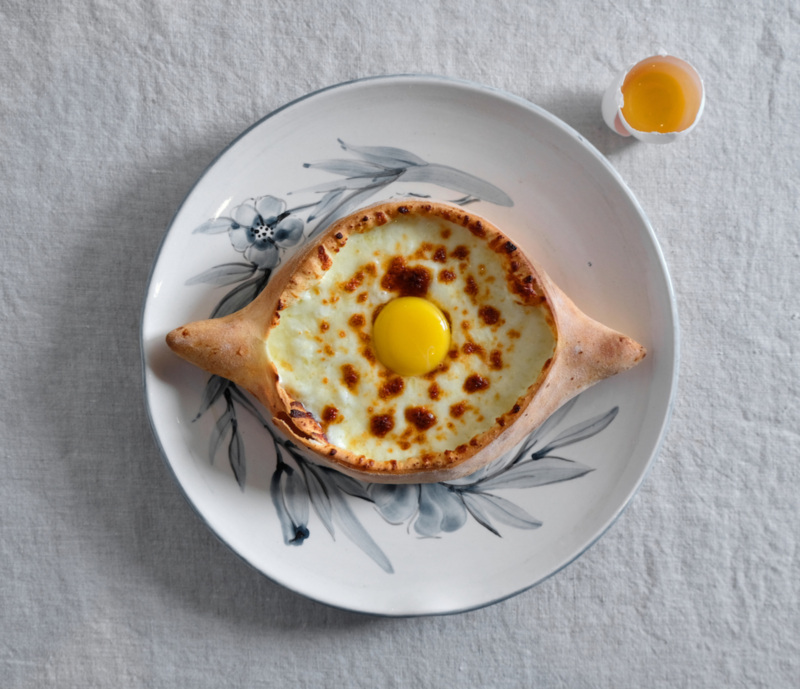

In recent years, Americans began discovering Georgia’s rustic-refined multilayered cuisine: think cheese-oozing breads, sizzling skewers called mtsvadi, complex stews, pleated dumplings the size of a baby’s fist, and intricate walnut-based sauces. In New York, a few Georgian places also started popping up, and the boat-shaped cheese pie called Adjaruli had become an Instagram darling.

Lucky for Chubinidze, she found an inspired collaborator in executive chef Nino Chiokadze who’d arrived in New York in 2015 and whose résumé included cooking for the Presidential Palace in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital.

“When I walked in and saw the custom-build tone (clay oven),” recalls Chiokadze, “ it stirred so many emotions. I could see that Tamara and I shared a vision — a mutual understanding that Georgian cuisine is about love and about sharing traditions through our healthy, natural flavors”.

Making it easier for Chubinidze to conjure up true Georgian flavors was the fact her father ran an import company bringing in things like ekala (edible buds from a wild thorny vine), jonjoli (bladderwort buds) that are usually pickled, and special cornmeal essential for Georgian mchadi breads and a polenta called gomi.

Chama Mama’s convivial vibe, lusty cuisine, and interesting Georgian wines have been such a success, there’s now a second Manhattan location on the Upper West Side, and a stylishly cozy Brooklyn Heights outpost opened last summer. A third Manhattan spot is also in the works.

“And in May we’re expanding our Chelsea location with a catering hub,” says Chubinidze, “where people will find real Georgian food to take out. It’s all been so exciting!”

Here are five dishes not to miss at Chama Mama — and the stories behind them.

Khachapuri

“In Georgian, ‘puri’ means bread and ‘khacho’ is cheese curds, and our khachapuri tradition is really old and so incredibly varied,” explains chef Chiokadze. “We have at least 50 varieties. Not even Georgians know all the types.”

The most ubiquitous version is the Imeruli (from Georgia’s central Imereti region): a flat round bread which Chiokadze makes with a blend of three briny cheeses and dough slowly fermented with a smidgeon of yeast. “Imeruli is what we eat for breakfast, dinner, or lunch,” says Chubinidze. “Every family makes it, and when it gets cold, we fry it in butter until it gets crispy.”

“As for Adjaruli,” she continues, meaning the boat-shaped open-faced khachapuri crowned with an egg, “it’s more of a weekend brunch specialty you eat at a restaurant. It’s a standalone dish, because it’s so filling and rich.” Adjaruli comes from the Black Sea Adjara region where, according to Chiokadze, women made it for fisherman [hence the boat shape] with the sun-like egg signifying luck and good weather. Since many customers don’t know how to eat it, Chama Mama servers twirl and mix the egg into the cheese filling — showing diners how to dunk pieces of yeasty fluffy crust into the molten savory lava. “Of course, our guests [like yours truly] instantly whip out their phones to record it,” grins Chubinidze. “Which is how Adjaruli became such a media star!”

“Khachapuri tell stories of our regions, their cheeses, and their traditions,” Chubinidze sums up. “On our menu we put them under a section called Puri Guliani with other filled breads. Lobiani, for instance, from the highland Racha region, has a filling of lobio (beans), while kubdari is a meat-filled pie from mountainous Svaneti nearby.”

Pkhali

“Pkhali are their own big story” says chef Chiokadze about Georgia’s signature preparations of cooked seasonal veggies blended with pounded walnuts, garlic, and spices, several of which are featured on the restaurant’s Taste of Georgia platter.

“People think of Georgian food as cheesy and meaty,” Chubinidze explains, “but in Imereti, for instance, where the chef and I come from, the cuisine is more frugal. We use wild greens from the field or right by our fence, and make them more nutritious and heftier by adding crushed walnuts. Almost any vegetable or mushroom or green can be prepared that way.”

Chama Mama offers at least 10 different pkhali: roasted pumpkin in fall; chive-like ramson in spring; beets, spinach, red beans, eggplants, and jonjoli. For the sauce, Chiokadze pounds walnuts, garlic, onion, lots of cilantro, dried coriander, wine vinegar, and utskho suneli, blue fenugreek that’s the sine qua non of Georgian seasoning. “In the Imereti region, pkhali is a typical lunch dish” she says, “served at room temp to spread on the cornbread.”

“Pkhali is food of peasants and villagers,” explains Chubinidze. “What I love is that it’s so refreshing and seasonal. Even the walnuts are fresh, and the vinegar is often homemade, because we’re a wine country”.

Khinkali

Khinkali, the large floppy Georgian soup dumplings with pleats resembling intricate turbans are reason enough to book a table at Chama Mama. Chiokadze makes hers with a variety of fillings: herbed lamb; a robust pork-and beef combo called kalakuri; herbed mushrooms; plus a more unusual cheese version called kvari that she tops with a minted yogurt sauce.

About the art of consuming khinkali: Hold a dumpling by its lumpy knot, carefully bite through the pouch, and experience something like ecstasy as the peppery broth dribbles into your mouth. “Eat it with a knife fork, and it’s ruined!” Chiokadze declares, adding that good khnikali are usually measured by the number of pleats in the pouch (they can go up to 12).

“Khinkali is a Georgian ritual of its own,” says Chubinidze. “You go out to eat them and nothing else, usually at a special place in the mountains. It’s a weekend thing, often after a hangover because the rich broth inside is so restorative. People order at least 50 or 100, have their chacha [Georgian grappa], and spend the whole day [eating]. When your dumplings get cold as you’re toasting and drinking, you send them back to the kitchen to be fried. Come April, we’re going to start serving fried khinkali for brunch,” she adds. “To tell the story of how Georgians do it”.

Sauces

Georgian might be one the world’s most saucy cuisines, with dishes named after the sauce they are cooked with or served in, and with bowls of zesty condiments always on the table. Not surprisingly, Chama Mama’s menu of sides includes Georgian classics such as harissa-like adjika, and the tart aromatic plum sauce, tkemali.

“At a supra” says Chubinidze, “you’ll have different sauces on the table depending on the region. A tomato-based sauce, for instance, will taste different from place to place. Then there are seasonal sauces, such as our tkemali, made from tart red or green plums. Each spring and summer, every house in Georgia smells like celebration as big jars of sauce are made for the winter, and to be given to friends. Grandmas and moms go to the bazaar, they make enough for a year. Tkemali tastes good even on bread. At Chama Mama, we serve it with mtsvadi [kebabs], cold beets, and our famous crisped smashed potatoes.”

“I can talk about tkemali forever!” exclaims Chiokadze. “I make a special one with the green sour plums we import from Georgia, flavored with tarragon. I also make a spicy special adjika with my own secret spice mix, chilies, a little tomato, and the delicious roasted sunflower oil we also get from back home. And we started doing an Imeruli adjika, which is totally different: made with crushed walnuts, spices, and roasted onions. It’s usually served at a special supra for wakes. So you don’t get to taste it too often, not even in Georgia.”

As an example of a particularly saucy dish on menu, there’s Megruli kharcho. “Most people know kharcho as a beef soup,” says Chiokadze, “but the word refers to the selection of spices called kharcho suneli — something like curry. Megruli kharcho is a walnut sauce flavored with coriander, blue fenugreek, Imereti saffron [crushed marigold], and dried peppers. They make it in the Samegrelo region with chicken or beef, and eat it with white grits that we serve grilled. But it’s also great with roasted mushrooms or vegetables.”

Pelamushi

Georgians are serious grape people with a viticultural tradition that goes back 8,000 years. “We love winemaking, toasting, and drinking,” says Chubinidze. “Our supra feasts are a kind of therapy: you toast one another with wine, you dance and sing, and quote poetry. A supra usually goes on for hours, and by the end, nobody wants any sweets, just more wine. But pelamushi (grape pudding) is perfect! It’s made with thickened grape juice; we have grapes in such abundance. It’s light, a wonderful palate-cleanser that can be eaten warm or cold depending on the season. It’s really the only traditional dessert we have in our country!”

Chama Mama’s pelamushi is outstanding, thanks to chef Chiokadze’s personal touch of using two kinds of grape juices: red and white. “I cook them apart,” she says, “flavoring the red with a dash of cinnamon and adding a touch of citrus to the white. I thicken them with a little corn and wheat flour to help them set, then mold them separately before combining them together and sprinkling them with nuts.”

And thickened grape juice is also used, explains Chiokadze, for the beloved Georgian candy, churchkhela, which involves nuts dipped in this juice and dried on the string.

“According to legend,” says Chubinidze, “when God was dividing land between different nations, Georgians were too busy feasting to show up to claim theirs. In the end, God was so impressed he gave them the land he reserved for himself.” At Chama Mama, one can see why.

All three locations of Chama Mama are open daily for lunch, dinner, and weekend brunch.

Anya von Bremzen is a James Beard Award-winning book author and journalist based in Jackson Heights, N.Y. Her latest book, “National Dish,” was published last year. Follow her on Instagram. Follow Resy, too.

Discover More

Stephen Satterfield's Corner Table