Really, Is Everyone a Critic?

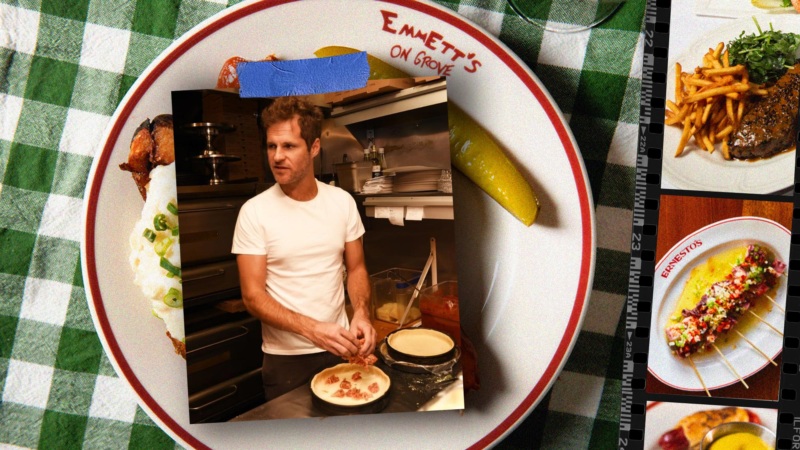

We’re proud to debut Resy’s first columnist, Mahira Rivers, and her column, Taste Matters. Rivers is a writer, critic, and former anonymous Michelin Guide inspector. In this and coming columns, she will tackle the questions that help define restaurants, and taste, today: Who sets the standards for deliciousness in a quickly changing world? How has the universe of great dining expanded? And what do diners expect in an era of ever-diversified taste?

▪️

Leila. Amara. Soraya. These are just a few of the names* I used to make reservations when I was a restaurant critic for The Michelin Guide. But the thing is, none of those are my real name. During my time at Michelin, the cardinal rules for all inspectors were that we remain anonymous and pay for our own meals — with a corporate card, of course. And the best way to fool even the canniest of reservationists is to blend in, to fly under the radar, to never use the same name twice at the same restaurant.

So, it’s not an exaggeration to say that coming up with a new alias every few months was a vital part of my job. Assigning myself a new identity required some effort, but anonymity was a breeze. I often dined alone, but so did a lot of other people. I took pictures of my food just like everyone else at the time (this was around 2014 and the movie “Foodies” had just come out, for context). Blending in while dining out amidst a food-obsessed public in the age of social media one-upmanship was a piece of cake.

But there was slightly more to it than that. On one of my first trips to Chicago as an inspector, I was eating at a fine dining restaurant, alone, and when my bill arrived, the server told me that a nearby table of four older, white diners had paid for my meal. I was completely caught off guard. What does one do when an unsolicited group of people you’ve never met surreptitiously foots your $150 dinner bill? But more important, I had technically broken one of Michelin’s cardinal rules. I didn’t pay for my meal. I was going to lose my job!

I didn’t get fired. I did have to deal with a few raised eyebrows, though. My boss was worried about the other cardinal rule — that somebody at this restaurant had discovered that I was a critic.

My take was slightly different. The restaurant critics I knew of at the time, the ones with bylines in the national press, were overwhelmingly white and more often than not, they were men. I didn’t exactly fit the template. It was a boon for my cover, but it presented an interesting thought exercise: What should a critic “look” like? And who gets to be one? If critics have the authority to distinguish between good and bad, an inherent value ranking, then who do we trust with this power? I can’t say for sure, but I suspect that four-top in Chicago didn’t think that it would be me.

An expanded role

By definition, a critic’s job is to cast judgement. The word comes from kritikós in Greek, which means discerning. But, in addition to deciding if the food is good or not, the best restaurant critics also contextualize a restaurant. Whether it’s making sense of an ingredient, a dish, a chef or even a city, they offer insights to diners looking for inspiration, elucidation and maybe a little bit of entertainment. In their earlier days, and especially in the United States, critics limited their observations to the food on the plate. Today, the scope of what’s relevant to a review, at least one published for public consumption, has grown as the importance of restaurants in culture has grown.

A good assessment nowadays reads more like broader cultural criticism, taking into account history, politics, economics and, especially, the biases that are inherent to some but invisible to others. The form is changing, at least in part, because the subject — meaning, the cuisines that are now part of the American canon — has expanded dramatically to become more inclusive in recent years. And diners are changing too, demanding more than a simple recitation of what’s good to eat.

Just as there may be a tendency to instinctively picture a restaurant critic as a white male, in spite of the prominent critics of color who are working or who have worked at major publications, there is also a Euro-centric bias in what foods have historically been associated with the aesthetics of good taste. The idea that some foods can taste good and still not be “in good taste” is another thing I spent a disproportionate amount of time thinking about as a critic. That unspoken hierarchy of haute cuisine was always in the back of my mind, and as an inspector for Michelin, the gatekeeper of a specific kind of taste, at least in fine dining, it was hard to ignore the dissonance.

▪️

The bigger issue, for me

at least, is that when

the profile of a critic is

so narrow, and the biases

so uniform, how relevant,

really, is the criticism?

▪️

My personal opinion is, whether fine dining is your cup of tea or not, it exists everywhere, in almost every culture. It might be framed as a French influence, but surely the idea of exquisite gastronomy both predates and exists outside of French haute cuisine. Whatever its earlier European influences, the modern tasting menu, one of the defining trends in fine dining today, is now rooted as much in the refined Japanese art of kaiseki.

The bigger issue, for me at least, is that when the profile of a critic is so narrow, and the biases so uniform, how relevant, really, is the criticism?

The restaurant critic is trusted as an expert because she is a lifelong student of food or, more specifically, of eating. Put in the time, eat all the food, and you, too, can develop an expert’s “delicacy of taste,” as the 18thcentury philosopher David Hume described it. This was a nice way to think about the constant slog of my life on the road as an inspector, eating lunch and dinner every weekday, accruing more airline miles, hotel points, and calories than I cared to count.

But the specifics of the experience have to be as important as the experience itself, because what good is 10,000 hours of eating escargots and blanquette de veau when you’re sitting in front of a bowl of the finest chocolate-brown mole poblano?

When I started at Michelin, I believed that my background would be an asset: I am Pakistani but I grew up in Hong Kong. And while I understand the cultural influences of the U.S. and Europe, it’s Asia that sits at the center of everything I know and love, which is the perspective I bring to each meal. Surely my global experiences could be beneficial to the task of eating across one of the most culinarily diverse countries in the world.

At one memorable meal at a now-closed New York restaurant, I ordered a dish that came with a ball of deep-fried milk — a technique I had first seen at a Buddhist Cantonese restaurant in Hong Kong. Though it resembles tofu, it isn’t, and the process of frying a ball of milk is completely different than frying a ball of tofu. I immediately understood the skill in the kitchen and the flex of the chef. Without the relevant knowledge, the artistry is easier to miss.

The ‘thorough generalist’?

I chased that knowledge voraciously, but truthfully, the idea of an expert in a subject as broad and unknowable as food is a chimera. Even today, after thousands of hours, it feels sometimes like I’ve barely scratched the surface. Can a critic, even one with a trained palate, measure up to every niche expert out there? Does a generalist’s opinion, even a very thorough generalist, matter in the face of the all-knowing hive of the Internet? And what is the weight of one expert over any of our memories and emotional connections to a dish or a cuisine? If every bite we eat is colored by the fullness of our individual experiences, maybe the only taste we can truly be confident in is our own.

And I still contend with these questions, even as restaurant critics have grown more diverse and the prestige of Euro-centric fine dining has started to wane here in the United States. I think about the overall utility of a concept like “good taste,” which implicitly requires that something else is bad. Ultimately, the point and the goal of these reflections is to show that the traditional hierarchies in food culture, and who gets to set them, should always be up for discussion. And now, more than ever, that discussion is being pushed to the fore.

One of my last meals as an employee of Michelin was at one of the finest dining rooms in Paris. It was a sentimental ending; a fitting place to sit and reflect on the thousands of meals I had eaten as a critic all over the world. From the ultra-luxurious chef’s counters to the soul-satisfying indie restaurants, which I would happily return to again and again, it had been quite a time. I wondered about the next thousand meals, too, and how they would compare.

Regardless, after almost five years of aliases and anonymity, I looked forward to the day that I could book a reservation under my own name. In Arabic, and this is true, it means expert.

* The names in the essay have been changed in compliance with the nondisclosure agreement I signed when I left Michelin. But the point remains — a fake name is a fake name.

Discover More