How Crustacean Changed America’s Vietnamese Fusion Landscape

When Helene An arrived in California as a refugee and started melding her native Vietnamese cooking with French and Chinese flavors, she wasn’t intentionally trying to create anything resembling “fusion cuisine.” “Nobody thought about the word ‘fusion’ [back then],” Helene says. “I just did it because I wanted to change the palate of Americans.”

But as the chef and owner of Crustacean achieved more success and began expanding her empire from its humble beginnings in the Bay Area, Helene developed a reputation as “the mother of fusion cuisine,” complete with inductions into the The Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center and California Hall of Fame. In 2002, the Oxford Dictionary added the phrase to its lexicon.

As Helene turns 80 this year, she reflects on the past, present, and future of fusion cuisine as it relates to her enduring culinary legacy, which spans some 50 years, from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Helene’s children and grandchildren have followed in her footsteps, overseeing the family’s restaurant group, House of An. In addition to Crustacean’s Beverly Hills and San Francisco outposts, the family’s portfolio includes Santa Monica’s Tiato Kitchen Bar Garden and An Catering, Costa Mesa’s AnQi Bistro, and the Bay Area restaurant that started it all, Thanh Long.

To understand the Crustacean of today, it’s helpful to look back at where it all began.

As a child in the Imperial City of Hue, Helene lived a life of privilege as the daughter of an aristocrat and advisor of the royal court. She spent time watching her family’s three chefs, each of whom prepared a different type of cuisine: French, Vietnamese, and Chinese. But in 1955, Helene’s pampered lifestyle came to a screeching halt as her family fled North Vietnam after it was overtaken by Communists. It wasn’t until Helene married Danny An, a colonel in the Vietnamese Air Force and the son of a wealthy industrialist, that her life regained some of its earlier trappings.

It was fortuitous that in 1968, a few years before the Communist takeover in Vietnam, Helene’s mother-in-law, Diana An, had traveled to San Francisco. On a whim, Diana bought an Italian deli (the owner at the time convinced her that if she had a business in the U.S., she’d be able to travel freely to and from Vietnam at her leisure). Initially, Diana changed little about the deli, which sold hot dogs and subs. But she did add two new dishes —Vietnamese fried spring rolls and roasted whole Dungeness crab — in 1971, when she changed the name of the restaurant to “Thanh Long.”

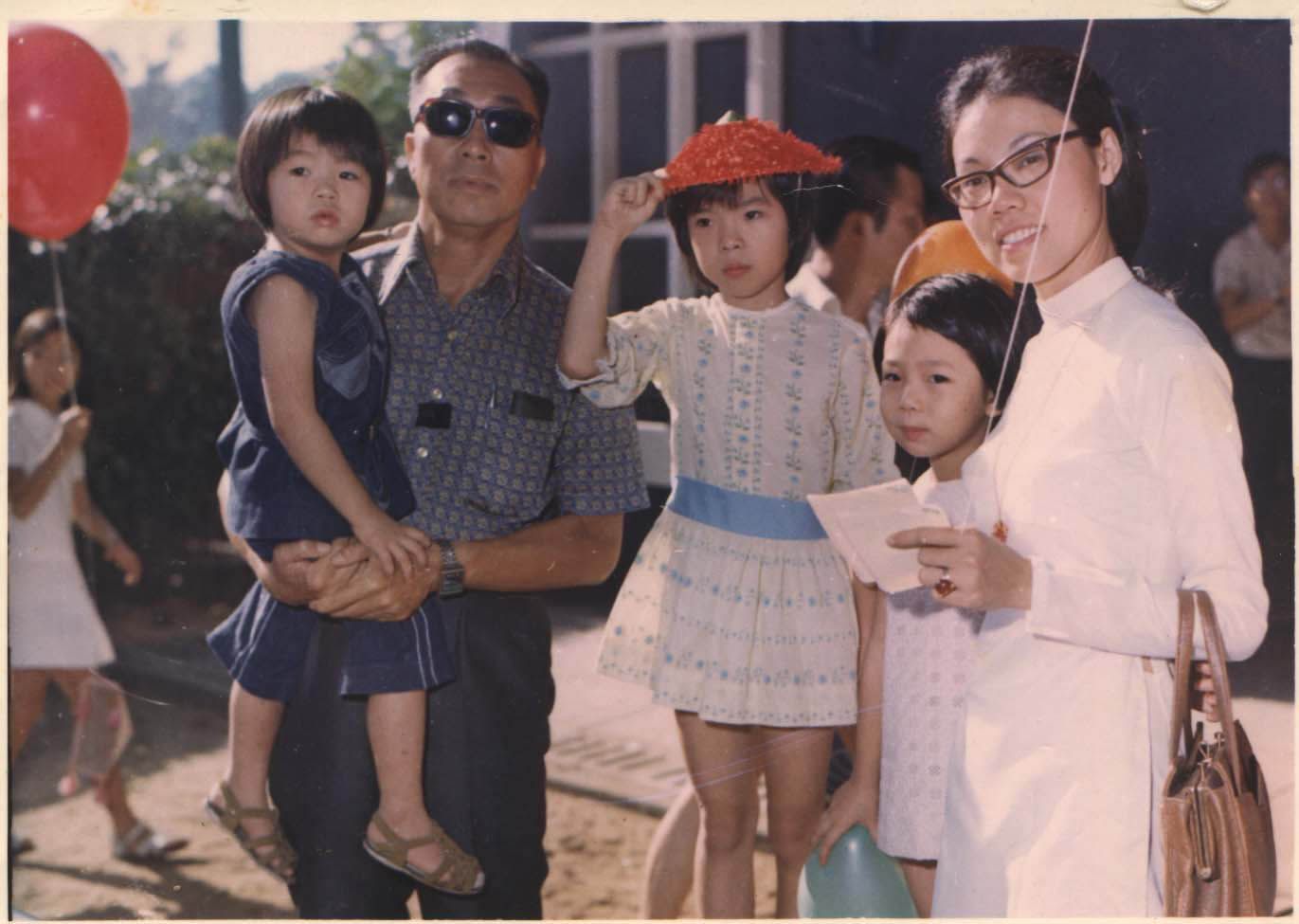

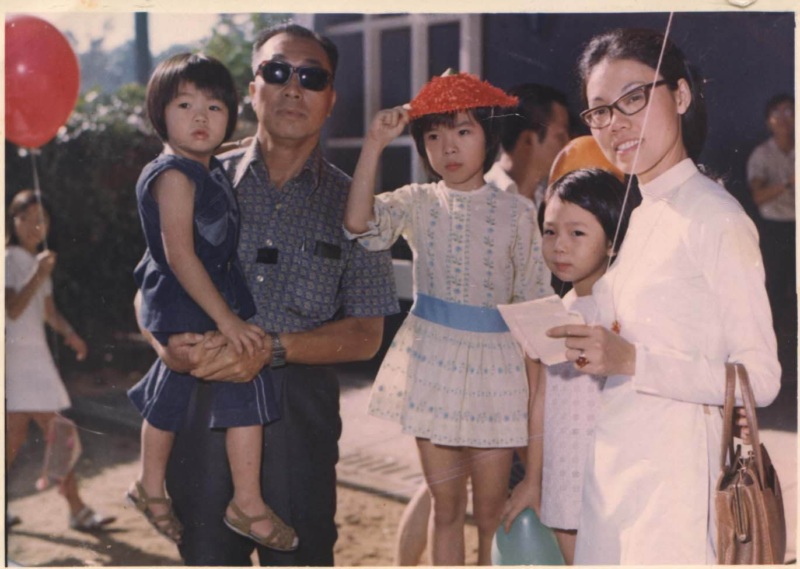

The lifestyle the An family enjoyed in Vietnam ended once and for all during the Fall of Saigon in 1975. Fleeing the city, Helene and her children were separated from Danny, who was on active duty, before they were able to reunite at a refugee camp in the Philippines. The family was sent to Southern California before Diana sponsored them to move to San Francisco, where she already was living with her husband. It was there that multiple generations of Ans all began living together in a cramped one-bedroom apartment. Helene worked long hours at multiple jobs and later focused her efforts into keeping Thanh Long afloat.

“Ever since I’ve known my mom, all I know is she works really hard,” says Helene’s daughter Catherine An (of Tiato and An Catering). “I never saw her because she was constantly working.” Helene slowly began changing Thanh Long’s menu, which was a mix of Italian and Vietnamese dishes, into her own fusion style, incorporating flavors of Vietnamese, French, and Chinese cuisines. Her efforts paid off.

When Thanh Long first opened, there were only 10 seats, but as the An family settled into their new life in San Francisco, the restaurant grew in popularity, and would eventually be declared one of the first Vietnamese restaurants in the city. Seating expanded to 240, and droves of people, including celebrities like Robin Williams and Harrison Ford, lined up for Helene’s cooking — particularly her signature garlic noodles.

Although Helene keeps the recipe for her creamy and umami-laden garlic noodles recipe a closely guarded secret — even going as far as creating a “Secret Kitchen” in her restaurants with only a few trusted folks privy to entering and seeing the magic behind the noodles — there have been countless attempts at copycat versions. Even food writer J. Kenji López-Alt recently created a version in her honor for New York Times Cooking, which included ingredients like butter, 20 cloves of garlic, oyster sauce, fish sauce, and Parmesan cheese.

Catherine didn’t realize the noodles were a fusion dish until she was a tween and one of her friends asked if the noodles were Vietnamese. “My mom told me, ‘No, I created garlic noodles because when we first came to America, Italian food, especially spaghetti, was the most popular [cuisine],’” Catherine says. “Garlic noodles were her version of spaghetti. She was trying to attract more customers.”

As Thanh Long’s business grew, so did Helene’s family, as she gave birth to two more daughters. 20 years after arriving in California, the family opened their second restaurant, Crustacean, in 1991 in San Francisco’s Nob Hill neighborhood. Crustacean was the brainchild of Helene’s daughter Elizabeth, who longed to combine her love for fashion, design, and her mother’s cooking into an upscale Vietnamese dining experience.

Opening Crustacean was a huge financial undertaking and risky venture for the family, and it wasn’t until San Jose Mercury News food critic David L. Beck wrote a glowing five-star review that the investment paid off. He wrote, “By the third forkful of Helene An’s garlic noodles, I had a plan. I would divorce my companion, marry An, get the recipe, divorce her, and remarry companion No. 1. A man must be flexible, though. Shortly after the crabs arrived, I was revising the last part of that plan to include (a) emergency deliveries to the South Bay, or (b) bigamy.”

With Crustacean’s success ensured in the Bay Area, Elizabeth, who was living in L.A., turned her attention south. She opened a second Crustacean location in the heart of Beverly Hills in 1997. The opulent two-story restaurant was outfitted with a bamboo garden and a snaking 80-foot-long aquarium walkway built into the floor and filled with koi fish. It was an instant hit. Opening night brought out a line of 500 people. Esquire named it among the top ten restaurants in the country, and more celebrity clientèle, including Leonardo DiCaprio and Kim Kardashian, came calling.

The An family started to notice some differences between the San Francisco and L.A. markets when it came to fusion cuisine. Elizabeth recommended that her mother create a longer menu for Angelenos because of the city’s diverse population and tastes. The Crustacean menu today includes elegant dishes like Helene’s take on bánh cuốn, a Vietnamese steamed rice flour roll filled with caramelized prawns and wrapped in a ravioli shape, blanketed in a light beurre blanc and topped with a fish sauce foam. Her crispy langoustine rolls, reminiscent of a Vietnamese chả giò, are adorned with dollops of Royal Kaluga caviar in a pool of a citrus sweet chili sauce. “In L.A., [diners] are more diverse and more open,” Helene says.

Catherine believes that openness stems in part from L.A.’s position as an international hub. “You have truly transient people in L.A. who are traveling in and out with Hollywood, whereas in San Francisco, there’s diversity but they’ve all lived there for so long,” she says.

Even as Helene is rightfully heralded as “the mother of fusion cuisine,” she still doesn’t approach her creations with the idea of cross-cultural collaboration in mind. “I really just make something I like to eat,” she says. “I think it’s important to eat healthy and I want to make things that I think people will like. I don’t think about fusion.”

Helene’s children play a role in keeping their mother’s cooking fresh and innovative, giving her suggestions for how to add en vogue ingredients and techniques to her process. The daughters are Helene’s pipeline to a new generation of diners, since she rarely has time to go out to eat at other restaurants.

Today, L.A.’s Vietnamese restaurant scene is vibrant, with many traditional restaurants in nearby Orange County, and the addition of newer upstarts like ĐiĐi in West Hollywood and Little Sister in Downtown. The latter two, in particular, feel like the natural progression of the foundation that Thanh Long and Crustacean laid, in that both are modern Vietnamese restaurants confident in serving traditional dishes tinged with Californian and global influences. At ĐiĐi, which is led by chef and TikToker Tue Nguyen, the menu features some fusion-style dishes, like a play on bánh xèo in the form of coconut crêpe tacos, and a Vietnamese coffee crème brûlée. At Little Sister, chef Tin Vuong combines Southeast Asian flavors with European techniques, like a salmon crudo in a coconut, lime, and chili vinaigrette.

50 years after arriving, Helene is finally able to see Americans become more accepting of the dishes she used to not be able to serve. Recently, a group of diners asked her to create a traditional Vietnamese menu for a special meal at Crustacean. She was elated to make dishes like bún ốc, an escargot noodle soup, and bún bò Huế , a spicy and aromatic beef noodle soup. “Now, people really understand Vietnamese food and are ready for traditional Vietnamese dishes,” Catherine says. “And they’re actually willing to pay for it.”

The An family has big plans on the horizon, too, gearing up to move the original Crustacean restaurant in San Francisco’s Nob Hill to a new and improved space in the Financial District in late summer. They’re also growing the Crustacean brand internationally through licensing deals.

“It was never my mother’s dream to be a famous celebrity chef,” Catherine says. “It was much more, ‘Okay, I have to feed my family and get back on my feet again.’” In the process, she’s built so much more — a delicious legacy and impact we’re still enjoying today.

Jean Trinh’s food and culture stories have appeared in Los Angeles Times, Food & Wine, and The New York Times. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram. Follow Resy, too.