The Making of a Sushi Master

Updated:

New York is in the grips of an omakase explosion. Every month, it seems like dozens of new sushi omakase restaurants emerge, places where diners willingly surrender to a sushi master’s 10-, 12-, and 15-course feasts. The competition is particularly fierce at the very high-end of the spectrum where there are often just a few stools at a counter, and they serve impeccable fish express air-lifted from Japan. The sushi at these hushed temples is a far cry from the pre-made California rolls that have become a deli-case staple, and a far cry from the sushi Eiji Ichimura encountered 43 years ago when he first arrived in New York.

In 1980, “there were just two serious sushi restaurants in the entire city,” the now venerated sushi master says. Ichimura worked at one of them after moving to New York as a 25-year-old, following 10 years in Tokyo as a sushi apprentice. To bring more depth of flavor to the middling fish he encountered, he began experimenting with aging techniques. And when he wasn’t catering to an expat Japanese clientèle, he would tailor his sushi to an American palate. “I would add sugar to the rice,” he says. “I don’t have to do that anymore.”

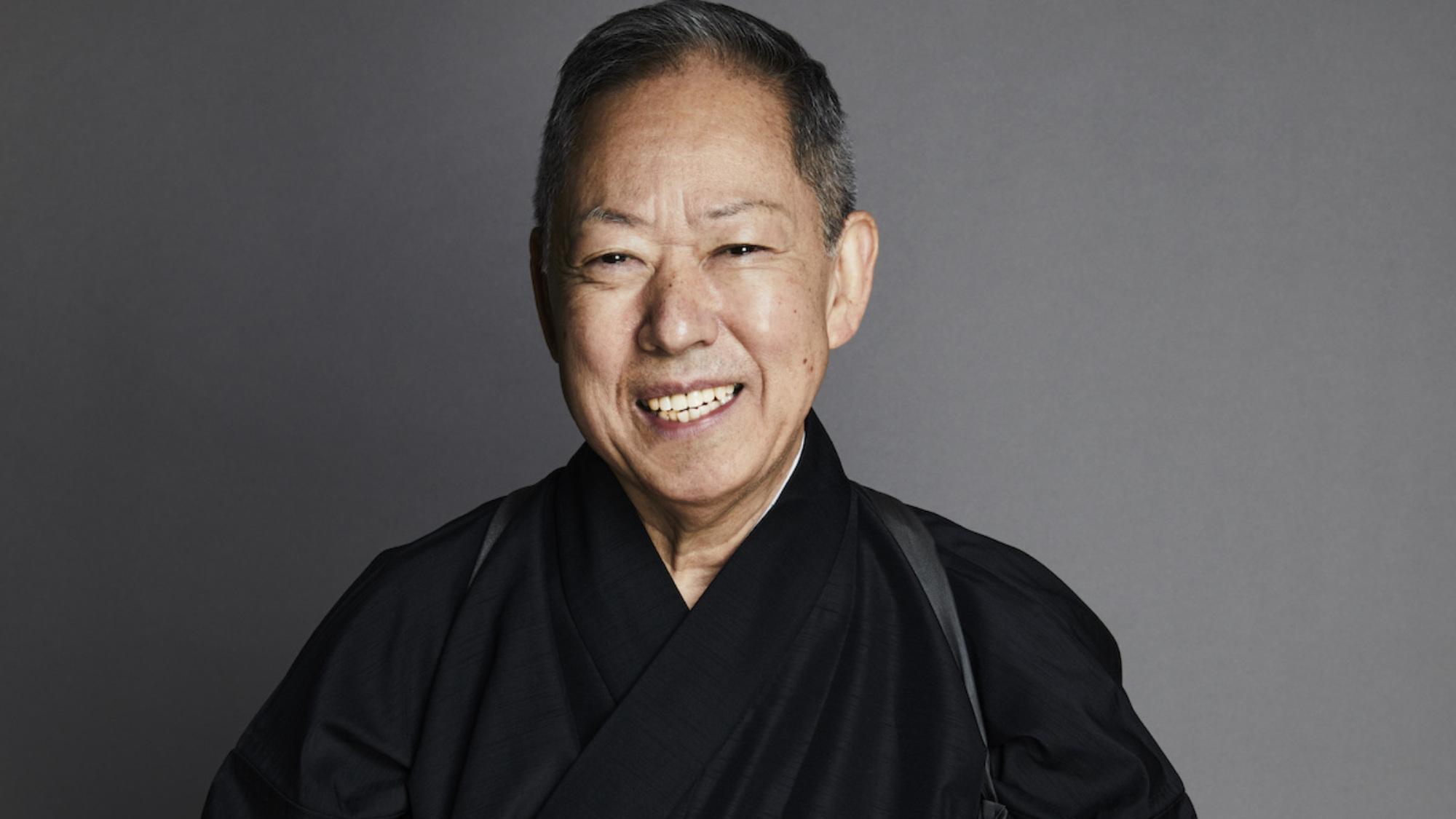

Today, Ichimura, who turns 70 this year, is one of the city’s original masters of high-end sushi omakase, known for his distinctive focus on aged and cured fish, and possessing a cult following among sushi snobs.

In 2003, he struck out on his own for the first time, launching his eponymous sushi restaurant on East 48th Street. Since then, he’s been a hard man to pin down. Working with fans who became business partners, he’s had a string of short runs across lower Manhattan, moving from Midtown to the curtained-off bar area at Brushstroke in Tribeca, to other diminutive nooks downtown at 69 Leonard Street and later Uchū on the Lower East Side.

After a post-pandemic hiatus, Ichimura is planning his return to the sushi scene next month with a 10-seat counter, opening as an annex to the French Japanese restaurant l’abeille in Tribeca. This time, he promises to stick around for a while. “We wanted to build him his legacy restaurant,” says Rahul Saito, a partner in l’abeille and in the new sushi bar.

The Early Years

Ichimura grew up in working class Tokyo, with a father in construction and a schoolteacher mom. He developed an interest in food early on which, in 1970, when he was 16, led to an apprenticeship at a neighborhood sushi bar. “Back then if you wanted to get into the food business you needed to start early,” he says. The entry-level position began at the sink, washing dishes. He would spend three years there, observing — practicing his sushi skills at home in his off hours — before he was officially allowed to touch fish. To instill the muscle memory needed to quickly mold rice for nigiri, he would squeeze a damp towel in his palm, over and over, hundreds of times a day.

When he was 21, he moved to a more celebrated sushi bar, Sushigen, a popular hangout for off-duty chefs near the original Tsukiji fish market in Ginza. He spent five years there working with some of the best fish in Japan, traveling to the market daily at 5 a.m. After assisting from the sidelines for four years, he was finally allowed to serve customers directly. A year later he moved to New York.

America Calling

After a decade rising through the ranks as an apprentice, Ichimura was ready for his next challenge. A colleague from Tokyo had been hired to work in New York at Take Sushi, one of the few authentic sushi bars in the city. He invited Ichimura to join him there. The young sushi chef had heard amazing things about North Atlantic bluefin tuna — the most prized monster fish weren’t yet shipped back to Japan. “I came for the job,” says Ichimura, “but mostly I came to learn about American fish. I had to see those giant maguro for myself.”

Ichimura touched down in New York as a new decade was dawning, catching a Pan-Am flight from Tokyo in the summer of 1980. It was his first time overseas, and his first time on a plane. The first meal he remembers was a king-sized burger. “I couldn’t believe how huge it was,” he says. He lived two blocks from work, at 46th Street and Lexington Avenue. He worked long hours. After a few years, he began to develop his own sushi style. When he considered moving back to Japan, as he often did, he thought about the untapped market here in New York. “There was virtually no competition,” he says. “There was an opportunity to do something better.”

For 20 years, Ichimura bided his time, honing his skills, finding his own voice as a chef. Through the 1990s he worked his way through many of the new, high-caliber sushi bars that began to proliferate following the success of Nobu in Tribeca. “Before Nobu, Americans only wanted sushi rolls; nobody wanted nigiri,” he says. “Nobu changed everything.”

Finally, in 2003, Ichimura opened his own place, with the backing of a young physician who’d become a big fan of his food. At the midtown sushi bar, simply called Ichimura, he focused on omakase, serving carefully calibrated, hyper-seasonal multi-course meals, featuring fish that was sometimes aged for weeks. He soon developed a cult following. Writer Susan Sontag, who lived nearby, became a loyal regular. If she could travel to space, she once told an interviewer, she’d invite Ichimura, her “sushi astronaut,” along.

A Style All His Own

Ichimura spent countless hours developing his own approach to the Edomae style of sushi, which dates back 200 years to the Edo period, a pre-refrigeration age when salt and vinegar were essential to keep fish from spoiling. Honing his technique was a painstaking process of trial and error, working to extract maximum umami while ensuring the fish didn’t begin to ferment.

Sometimes he would press fish flesh with kelp, extracting moisture while simultaneously adding umami. “There was no book I could consult; I taught myself,” he says. “There were a lot of failures, a lot of fish in the trash. I experimented in the fridge, in the freezer, using as little salt as possible.”

Each species, he learned, needed to be handled differently — the larger the fish, the more age it can take. Tuna might reach its peak after aging for as long as two weeks. Smaller, more perishable specimens, like silver-skinned kohada, might need just a few days. “Aging depends on how much fat content the fish has,” he says. “Depending on the season, it can vary even with the same fish.”

There was no book I could consult; I taught myself. There were a lot of failures, a lot of fish in the trash. I experimented in the fridge, in the freezer, using as little salt as possible.— Eiji Ichimura

Three Stars

David Bouley, the French American chef who, starting in the 1980s, helped put Tribeca on the map as a fine-dining destination, was a Japanophile who traveled often to Japan. In 2011 he opened his own Japanese restaurant, Brushstroke, on Hudson Street, in partnership with the Tsuji Culinary Institute in Osaka.

A few months after opening, he invited Ichimura to take over the bar area. There, Ichimura began serving an elaborate $150 per person omakase experience, separated from the dining room by a simple curtain. “At Brushstroke, I really started to show off my style of sushi,” he says, “an omakase meal at an omakase price.”

The tiny restaurant within a restaurant operated way below the radar for a few months, before New York Times critic Pete Wells strolled in for a meal one night. His three-star review, published in September 2012, called out “some of the most remarkable sashimi and sushi” he had “ever tasted.” Overnight, Ichimura at Brushstroke became New York’s new sushi sensation. “It got very busy,” says Ichimura. “And then the celebrities showed up.” Jay-Z and Beyoncé were regulars, along with Lou Reed and Japanese baseball star Hideki Matsui. Two Michelin stars soon followed. “And then it was a madhouse,” says Ichimura.

In the press, Bouley promised to build a standalone temple for his new star attraction, to add tanks for live seafood, and to enlist American fishermen to supply the restaurant directly. “David had a lot of ideas,” says Ichimura. “He gets inspired, without thinking too much, and dives right in.” None of those big ideas ever came to fruition. Instead, after internal squabbles between Bouley and his partners, Brushstroke closed in 2018.

Life After Brushstroke

Seeing the writing on the wall, Ichimura began looking for new opportunities months before Brushstroke’s demise. A regular at the restaurant, financier Idan Elkon, offered to build him a new spot nearby. Despite raves from his fanatical fanbase, the partnership lasted just a few months, ending with back-and-forth lawsuits. “I realize now I really didn’t know my partner well,” says Ichimura. A residency followed at Uchū, a 10-seat omakase counter on the Lower East Side. By the time the pandemic hit, Ichimura’s sushi was looking for a new home again.

The Last Dance

In the spring of 2022, Rahul Saito, a finance executive with a passion for fine dining, opened a new home for another chef without a kitchen, launching l’abeille as a showcase for the Franco Japanese cuisine of Mitsunobu Nagae, a protégé of the late Joël Robuchon. A few weeks after opening, Ichimura walked by. Saito had been following his work since Brushstroke. Accompanied by investors, Ichimura said he was walking around the neighborhood, looking at potential locations for a new sushi bar. “I texted him right away,” recalls Saito. “I said, ‘We should talk.’”

The new Sushi Ichimura will open barely a year after that fateful encounter, replacing a fast-casual poke spot. The jewel box will feature a 400-year-old golden screen painting, Amazonian-wood covered walls, and seating for 10 at its cedar counter. Along with a large sake selection, there’ll be fine wines available from the vast cellar at l’abeille next door. Ichimura will personally serve every single guest.

“As a chef, this is his last dance,” says Saito. “We want him to do exactly what he wants — and we’re here to support him.”

What to Expect at Sushi Ichimura

The Layout: There are just 10 seats at the sushi counter, with two seatings nightly (5:30 and 8:30 p.m.) from Tuesday through Saturday.

The Vibe: Expect exceptional food and an approachable, elegant dining room, says owner Rahul Saito. “It’s a warm mix of Japanese tradition, where you have the hinoki counters combined with Western décor, like the wood panels made from sustainably sourced wood from the Amazon in Brazil.” In other words, it’s meant to be cozy, welcoming, intimate, and comfortable. There will be jazz music playing softly in the background (it’s Ichimura’s favorite), and do take note of the design, especially the 400-year-old gilded screen depicting The Tale of Genji. During your omakase experience, expect to engage with Ichimura and his executive chef who prepare a majority of courses in front of guests.

The Drinks: Beverage director David Bérubé has compiled a list that highlights sake, including some rare varieties, beer, Japanese whiskies, and a wine list that’s heavy on white wines from Burgundy. Diners also have access to the full wine list from l’abeille, Sushi Ichimura’s sister restaurant.

The Meal: Sushi Ichimura serves a 20-course sushi omakase menu ($425 per person, not including tax and gratuity) that consists of seasonal appetizers, 12 courses of sushi and temaki, and ends with seasonal desserts that include ice cream and wagashi. Do look out for Ichimura’s signature uni caviar in a rice cracker, served as an appetizer, and a sea bass sashimi that gets ice washed in front of diners. The o-toro (pictured above) is also a highlight; it’s sliced into three thin layers to maximize the depth of taste you can get from the aged tuna. And do know that all of the fish served is flown in from all over Japan, from Kyushu and Hokkaido to Tokyo.

It’s All in the Details: Every dish is served on rare, antique Japanese lacquerware or ceramics. And what makes dining with Ichimura so unique is the special care Ichimura applies to dry aging each different type of fish. While longtime fans of Ichimura will recognize and appreciate many of his signature dishes, they’ll also be surprised with some of his newer dishes, too, like steamed scallops. “He’s evolving and making new dishes, but also keeping his traditions,” says Saito.

— Deanna Ting

Resy Presents

Omakase in America

- At Its Best, Omakase Becomes Special Because of Human Connection

- A Chef’s Ode to Sushi Omakase — and Shion 69 Leonard Street

- Top Chefs Explain Everything You’ve Wanted to Know About Sushi Omakase

- The Resy Guide to Omakase in New York

- In An Era of Luxe Sushi, Is the Greatest Tradition to Be Local?

- All About Jōji, a New Omakase Speakeasy from Three Masa Vets

- How Much Omakase Can New York Eat? The Shion 69 Leonard Team Has Thoughts

- The History of Omakase in Los Angeles, As Told Through 10 Restaurants

- Everything You Need to Know About New York’s Latest Omakase Restaurant, Kono

- J-Spec Wagyu Dining Is New York’s Newest Omakase Sleeper Hit