Call Dan Richer’s Pizza Exceptional. Just Don’t Call It New York Pizza

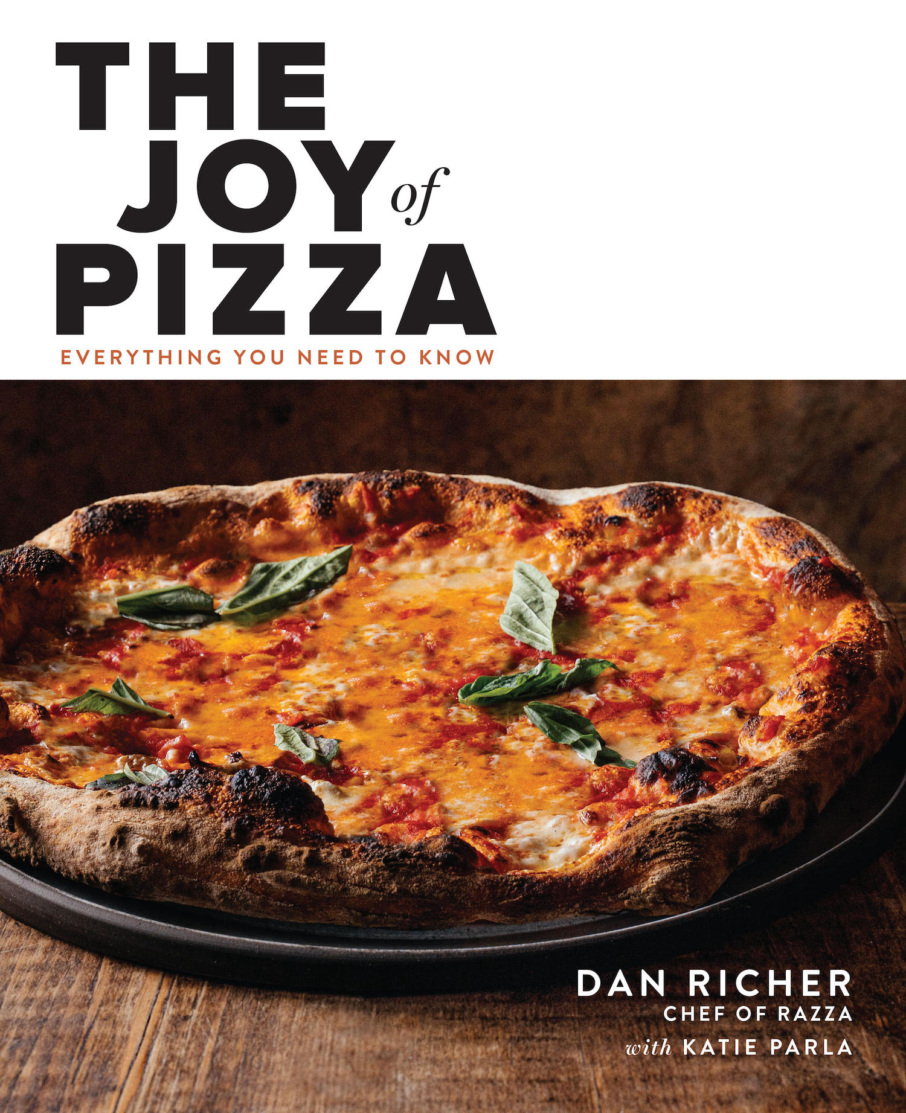

Dan Richer and coauthor Katie Parla are bringing their bestselling cookbook “The Joy of Pizza” to California on the first leg of their national book tour. Members of Global Dining Access by Resy have exclusive pre-sale access to tickets for three of their events. Join them as they appear in Los Angeles at Mozza on October 24 and Pizzeria Bianco on October 25; and in San Francisco, at Del Popolo on October 27.

On the table, in front of Dan Richer: hearty slices of sourdough bread; a plate of proscuitto; some sublimely ripe New Jersey tomatoes; three kinds of butter. This might seem odd, considering that Richer’s Jersey City restaurant, Razza Pizza Artiginale, is clearly known for the one thing that’s missing from the spread. Except it’s lunchtime. The oven won’t be fired for several hours yet.

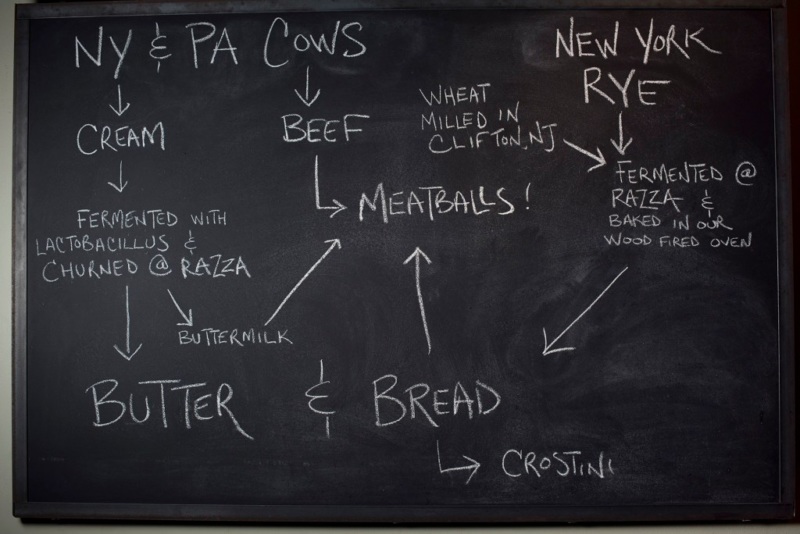

Also, we’re not discussing pizza. We’re considering the butters before us. One is the cultured version Richer has served for years at Razza, enough that his bread-and-butter service has as almost as much of a following as his pizza. The other two have been inoculated with cheesemaking bacteria (namely for Camembert and Roquefort), and aged for nearly three months. “You know how in France, there’s the cheesemaker, and then the affineur?” he asks, referencing the distinct trade of cheese aging. “Well here, we’re trying to be both.”

- What Makes Pizza in New York So Special?

- New York's Favorite Pizza Slices

- New York’s Favorite Sit-Down Pizzerias

- New York’s Most Beloved Neighborhood Pizza Spots

- Melissa Rodriguez Is Ready to Reboot Fine Dining In New York. But First, Pizza.

- Wylie Dufresne Finds His Ultimate Challenge (Spoiler: It’s Pizza)

If this sounds off topic for a guy whose pizza was crowned in a 2017 New York Times review as the best pizza in New York, then you don’t know Richer. The story of his pizzas has always been a bit complicated, not even counting the fact that his achievement meant the best pizza in the city was, inconveniently, a river and a PATH ride away. But the pizzas at Razza — really, everything at Razza — are never just about pizza. They’re the result of Richer’s nearly two decades of considering everything that goes into pizza. That starts first and foremost with fermentation, which explains the experimental butters. (The Camembutter lives up to its name, in an almost disorienting way.)

This path began in his years just after graduating from Rutgers, when in quick succession he had one of those transformative trips to Italy, then found himself moving back home in the final days before his mother Robin died. The resulting grief would turn into pizza obsession, one that would culminate not only with Razza, but more recently a cookbook, “The Joy Of Pizza,” published last year, that includes a Pizza Evaluation Rubric — 56 questions that prod at the very soul of what great pizza can be.

Richer’s work is also benefitting from the long-awaited Great Pizza Awakening. It’s not just that great pizza can be found in nearly every American city. It’s also a recognition that pizza making is baking, and today we accept a degree of obsession around baking. Thus it’s hardly a surprise when Richer references “Tartine Bread,” which, with its 35-page core recipe, gave Americans license to fixate. (“Joy” doesn’t shy from this approach, expending nearly 110 pages on pizza dough.) At the same time, he is keenly aware just how recent this quest for great American pizza is. At one point, our conversation drifts to the baker Peter Reinhart, whose pizza writings two decades ago were considered almost unreasonably finicky.

This has clearly instilled in Richer a sense of humility. He refers to pizza as “a flatbread with condiments baked onto it.” And despite the fact that he has been anointed the keeper of the New York pizza flame, he is unequivocal: His pizza is actually not New York pizza, so please don’t call it that.

Actually, he will point out, most pizza in New York isn’t New York pizza. Needless to say, we had questions.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Resy: Let’s let’s talk about New York-style pizza. What in your mind is New York pizza?

Dan Richer: It’s pretty specific. It’s a specific size, right? Eighteen to 22-ish inches, typically produced in a gas oven. At least historically produced in a gas oven, because that’s the oven that was available from the 1940s until today. They were inexpensive to produce, and to procure as a pizzeria owner. So the style kind of developed around the oven. Obviously, pizza started way earlier in New York in coal-fired ovens that happened to be here because they were bakeries …

Like Lombardi’s, that was putatively the departure point.

Exactly. So, typically produced in a gas oven. Gas ovens have a maximum temperature, because otherwise it could turn into a bomb, right? So there’s a max temperature, the pizza has a certain length of time it has to bake to be fully cooked. With that comes structural integrity, because it’s baked for a long time. It’s crispier. We can pick it up with our hands.

And it’s consistent throughout. No Neapolitan. No puddles.

Definitely, yeah. And most of that comes from this style of oven, right? Neapolitan pizzas are produced in a Neapolitan style wood-fired oven with a pretty low dome. Really hot temperatures, and the pizza cooks for a much shorter time. So it’s a little bit less crispy …

That’s a super diplomatic way to put it.

It is without a doubt the absolute truth. I was driving around in a car right outside the Naples area with one of the best pizza makers in the world. His name is Franco Pepe. And he told me we are making pizza the wrong way. And at that moment I realized that we’re just fundamentally looking for different things in our pizza. Neapolitan pizza is supposed to be what it is, it’s supposed to be softer, much more pliable.

And they don’t slice it. It’s an individual thing. One thing I always appreciate about pizza in the United States? It is the most shareable food on the planet. It’s one dish in the middle of the table; everybody gets an equal slice of the pie. Neapolitan pizza is not that at all. It’s an individual thing. Everybody orders their own. It’s a fork-and-knife thing. You’re not using your hands.

But what’s also exciting is that we’re finally seeing this great pizza diversity across the country. We’re getting past the weird phase where everything was about Neapolitan, and the VPN, and having this direct link back to Naples.

I didn’t grow up in Naples; I don’t have this strong connection to it. I’m not looking for authenticity at all, because it’s just not where I grew up. It’s not what’s in my DNA. I grew up on a New York-style slice here in New Jersey that was shareable. I’ve traveled around Naples extensively, and I love that style for what it is. But it’s kind of like comparing a braised short rib to a steak. Right? They’re both part of the cow. They’re both beef, but they couldn’t be more different.

Also, what even is authenticity?

Exactly. Naples did a great sales job on us, and the rest of the world. Pizza makers think they need to import double-zero flour or San Marzano tomatoes and buffalo milk mozzarella from Southern Italy. They just sold us really well.

Because I don’t come from this long lineage of pizza makers, I question everything, and I do the research to backup the ideas. I wanted to know, like, why do I need to import this double-zero flour? So I started researching wheat and flour and fermentation, and I started visiting flour mills. And after doing the research? No, you don’t need double-zero flour. Same thing with tomatoes. I started visiting tomato canneries and farms. OK, the tomato is from San Marzano. Does that mean it’s good? Absolutely not. There’s great products and bad products everywhere you go.

It doesn’t just apply to wheat or tomatoes. It applies to pizza in general. Like if somebody says, pizza in Chicago is terrible. That statement is just …

What does that even mean?

It’s not fair, because there’s great pizza everywhere you go.

All right. Back to New York pizza. You’ve got the gas ovens, and the size and texture. So, Di Fara? Clearly New York pizza.

Yes.

New York-ish. Mark [Iacono] is one of those guys who’s not going to follow the tradition of, you have to use this product. It has to bake for this long. He’s making pizza in a woodfired oven that he built from hand. And he’s putting pizza together in a way that he loves. So you can’t really say it’s one style or another. New York-ish. He’s in New York, right? He grew up in New York eating that pizza. So it’s in his DNA. But he’s taking a lot of liberties that would not be called New York-style pizza by by purists.

Totonno’s. Do they get grandfathered in, because they they had ovens before there were gas ovens?

Yeah.

Everyone has their Platonic pizza, the pizza that for them, it’s their departure point. You grew up in in Jersey, and went to Rutgers. What was your departure point?

It’s always that childhood pizzeria that you that you grew up going to. Mine was Pizza Village in Aberdeen, N.J., which funnily enough is now a location of Denino’s. I still go there every now and then.

I just remember walking into this place and right inside the front door, there’s the counter where the pizza maker is making pizza in front of you, and I loved watching as a kid. And as soon as you open the front door, you’re not only seeing the oven and the guy tossing dough, and doing the spirals of syrup of sauce with his ladle, plus that gigantic bin of mozzarella cheese that you just wanted to dive into. But also, the aroma when you open that front door is unmistakably pizza. That’s the first thing that hits you. Pizza is this full sensory experience. You smell it in the air. You’re listening to the sound of the slicer pass through this crispy, freshly baked pizza. It’s amazing.

As soon as I started making pizza, I began visiting all the pizzerias that I could possibly visit, to develop my palate, to figure out what type of pizza I wanted to produce. Because I knew I didn’t want to make New York-style pizza. I knew I didn’t want to make Neapolitan-style pizza, I wanted to create something from me, that took into account all of my experiences, my childhood, my college career, my love of Italy.

How did you interpret the diversity of styles throughout New Jersey? Because there’s a lot. I think most people don’t know. But you go far south and you get mustard pie …

It’s a little weird.

I literally will not go through South Jersey without getting mustard pie.

I love that you love it. I can’t do it.

But speaking of authenticity, styles have flourished here.

In an area where every town has 10 pizzerias, you have to stand out in order to stay alive. So people do things that are crazy and different, like putting french fries on your pizza, which is not my thing, clearly. But you do it and sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.

Are there specific Jersey iterations you’re drawn to?

I like people that keep tradition in mind, and comfort in mind. Right? I’m not trying to stylistically change so much that it’s unrecognizable to my five-year-old son. I want to know that I can get a margherita or a plain slice and that it’s not going to be too weird.

There’s a place in Point Pleasant, N.J., that I go to all the time called Rosie’s. They are completely focused on all of those things. Remaining classic and traditional, but utilizing higher-level breadmaking techniques for their dough, understanding a little bit about tomatoes so that they can buy the best products for their sauce. They’re just deeply entrenched with making a better pizza than what came before them.

But the place I go to most often is the most convenient. It’s in between my house and my restaurant. And I go there on my way to work, after I go to the bank or the post office, doing my daily errands, and get a slice. I always talk to the owner because he’s always there making every pie. We talk shop for five minutes and then I’m on my way.

What’s the pizzeria?

It’s called Ray’s.

[Laughs] No one will ever find it!

It’s in Hazlet, N.J. The guy’s a character, the pizza’s great, and it’s super convenient. This is my comfort, right? I’m eating two slices on my way to work.

Because you’re not gonna get pizza at work?

Oh, I’ll eat pizza here every day.

Let’s talk about the expanding pizza revolution around the country. You’ll be traveling soon for your book tour. What about some places you’re gonna go? Like San Francisco, with Del Popolo and Jon Darsky?

I am very excited to make pizza with him. He’s more of the neo-Neapolitan thing, where he’s not following all of the rules of authentic Neapolitan; he’s breaking a lot of the rules because a lot of those rules need to be broken. It’s gonna be very interesting making pizza there. He has a Neapolitan-style oven. So our pizza is probably going to bake a little bit faster. So we might have to tweak the dough formula. Pizza making is super simple, you know? Dough, sauce, cheese …

Until it’s not?

You realize it’s extraordinarily difficult and complicated. I bought the right oven for the style of pizza that I want to make. We know how our air conditioner cools off the room, or doesn’t. We know how our refrigerator cools things. All of these little minute details matter so much. That’s why me taking pizza on the road is such a challenge. And I love it. I never learn more than when I make pizza outside of my comfort zone.

Anyways, there’s so many different styles in the Bay Area, you know, with its rich tradition of bread baking, Two of my favorites are actually in Berkeley. One is Cheese Board Collective. I cannot go to the Bay Area without stopping at Cheese Board. They do one or two styles of pizza, one salad a day. It’s employee owned. Got a little jazz band in the corner. And of course, because it’s the Bay Area, it’s a beautiful day every day. You just sit outside. The second is Emilia’s.

They’re both focused on … Look, pizza is a flatbread with condiments baked onto it, right? So they really tried to understand the breadmaking aspect.

What to Eat and Drink in New York Right Now

Your biweekly dose of recommendations on what to eat, drink, and see.

In L.A., you’ll be at the new location of Pizzeria Bianco, which originated in Phoenix. But what about L.A. pizza more broadly? This is the year it feels like L.A. has emerged as a pizza town.

I think L.A. is one of the best places on earth. I didn’t always love L.A., but probably five or six years ago, I flew out there just to just to eat, and fell completely in love. And every year I’m trying to go, like four times a year. Because it’s a city, but it’s got the beach. You’ve got mountains pretty close by and you have a ton of farmland, and a 12-month growing season. Visiting the Santa Monica Farmers Market is just mindblowing to a chef, where there’s 20 different varieties of citrus. Eight different types of avocados. I didn’t know there were eight types of avocados in the world.

Anywhere on the West Coast, going to a farmers market, you’re exposed to these amazing ingredients. As a chef, I want to make pizza there.

Now, I wouldn’t take anything away from my trajectory and being in New Jersey. We’re the Garden State, right? We have really good soil and farmland, although it’s kind of disappearing, because the real estate is so expensive …

I mean, the tomato season is short. But the tomato season is worth it.

Exactly. I’ve never tasted a better heirloom tomato than one grown in New Jersey. There are two farmers in particular; their tomatoes are above and beyond anything I’ve ever tasted. We’re able to get them when they’re still warm from the sun, which makes a huge difference. The texture, the flavor is unmatched. Even when you buy a tomato in a supermarket in tomato season that says it’s from New Jersey, it’s still a few days old.

And we have this sense of a deep culture surrounding pizza on the East Coast that I think is is not as rich on the West Coast. There’s benefits and detriments to both. Here, it’s hard to stand out as a pizzeria. So it really pushes you to learn more. Great pizza is easier to find on the East Coast, because there’s physically so much of it.

On the West Coast, it’s fewer and far between. But because they don’t have that rich history, they can take liberties, and experiment. And you look at places like Portland, Ore., with Sarah Minnick from Lovely’s Fifty Fifty, Scott Rivera from Scottie’s Pizza Parlor, Brian Spangler at Apizza Scholls. There are so many phenomenal pizzerias out there. And they’re all completely different. There is no one specific style. They’ve all developed they’re the styles of their own, putting the raw materials together in a way that makes them happy.

What about in between? Like Chicago.

I was just in Chicago at the end of July for a pizza festival. And the variety of different styles and what people are doing there is amazing. You know, people think of Chicago as deep dish, right? Unless you’re from Chicago. And then you know there’s the tavern style. Because Chicago is a giant city, right? And there’s all different styles, just like New York. Like, a majority of the pizza in New York is not New York style pizza. So to categorize an entire city based on one style of pizza, it’s just not fair to the rest of the pizza makers out there who are taking crazy liberties with style and technique.

What other cities have blown you away for pizza?

I love Indianapolis. Highly underrated as a food city. Not just for pizza, but for all types of food. I have very good friends in Indianapolis, and I’ve never had a bad meal there. Again, they are surrounded by farmland and where the ingredients are good, chefs want to be.

And elsewhere on the East Coast?

Miami’s actually pretty good these days. For pizza and and for everything culinary, Miami’s really blowing up. D.C. has got great pizza. There’s one or two places in pretty much every major city where you will get an amazing pizza.

We check every pizza, we check the bottom, the top, the sides, we’re evaluating it, whether it’s worthy of being served to a guest. And if not, we throw it in the garbage.

This sounds like a good time to bring up your Pizza Evaluation Rubric.

This is what my cookbook is based on, the product specifications I developed over 18 years. It started out as a way to guide the creation of my ideal pizza, with six or seven characteristics. Like, I knew I wanted the it to be structurally sound enough for me to pick it up with my hands. And I wanted to feel the crispness when my teeth bite through. I wanted the cheese to be fully melted, not just little half-melted pieces of mozzarella. I wanted the tomato sauce to have a balance of sweetness and acidity.

Then over time, I built on them, and got more specific, and now it’s almost 60 characteristics long. And it’s my training document for our cooks. Nobody starts to make pizza without me sitting down with them and talking through the rubric. These are the blueprints for our pizza. And it’s impossible to build a house without a set of blueprints, right? So we use these every day. We check every pizza, we check the bottom, the top, the sides, we’re evaluating it, whether it’s worthy of being served to a guest. And if not, we throw it in the garbage.

How often do you throw pizza in the garbage?

Pretty frequently. Our standards are tight. But also, our team is very good at making pizza. So we don’t throw that many pizzas away, comparatively. But there’s nothing wrong with throwing something out that is not going to be delicious.

I mean, pizza is a puzzle, right? And at first, it looks like a 10-piece puzzle. You know, dough, sauce, cheese, bake in the oven. And then the more you understand it, the more you realize it’s a 10,000-piece puzzle. I’m sure five years from now, I’ll say that it’s a 100,000-piece puzzle. Because it just keeps getting more interesting.

Because the rabbit hole has no bottom.

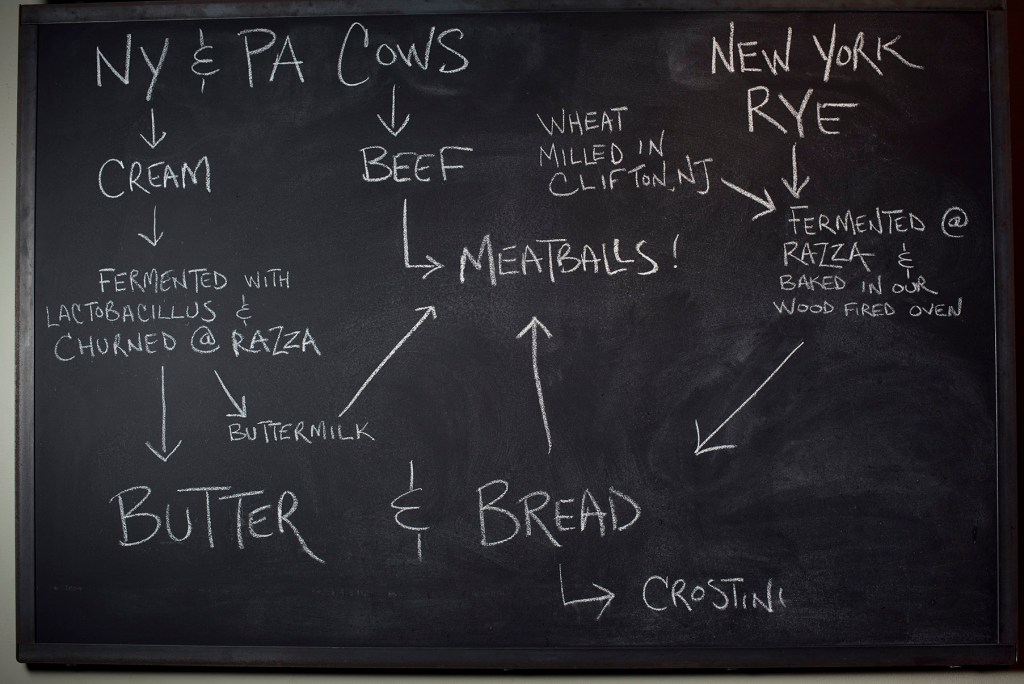

And for pizza specifically, a lot of it has to do with fermentation. That’s what is constantly changing. And once you start fermenting grain for bread, you want to ferment everything. So I love making pickles. I love making my own yogurt. We have a huge cultured butter program at the restaurant; we have five different butters that we make here.

And not compound butters. We’re actually fermenting cream. Sometimes we inoculate them with other cultures. Like Penicillium camemberti, which is the mold that makes Camembert and Brie. It’s butter, but it has it’s been aged for between two and three months. It’s got this powdery white coating on the outside, just like Camembert. It has the flavors of Camembert, but fundamentally and texturally, it’s butter. It’s crazy.

How did this evolve into the butter tasting you’re doing now at Razza?

I’m always after the elemental, and simplicity. So, there’s no simpler bread-condiment combination than bread and butter. Butter is one of those products where most of it is industrial. And it’s so rewarding to taste a product that you made that is better than any butter that I’ve ever tasted.

So we get to create a product again from agriculture. We see major variations in the flavor and color of our butter based on what the cows are eating. In the spring when they’re on fresh grass, it’s this bright neon yellow. In the summertime, the color dies back down, and then right around Labor Day, inevitably when my landscaper starts cutting my grass again, I know that the next week our butter is going to turn bright yellow again.

It led me down that path of thinking like a cheese maker, because there’s probably 1,000 different varieties of cheese in the world. But they’re all made with the same one ingredient, which is milk. So being naturally curious, I want to know how and why. And it comes down to these minute details that a cheese maker will apply every step of their process. Now, I have so many new ideas. We’re just limited by space. Like, we don’t have a cheese cave.

Yet.

Yeah, exactly. But I just think it’s so interesting that it’s all connected to agriculture. When you look at some of the big pizza chains like Papa John’s and Domino’s, you wouldn’t think that pizza is so connected to agriculture. But it is 100% agriculture, all of it, from the olive oil to the tomatoes, to the cheese to the salt to the wheat. It’s all nature. And the closer we can bring our product to that, inevitably, the more rewarding it is to make it. Also, the more delicious it tends to be.

Jon Bonné is Resy’s managing editor. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter. Follow Resy, too.