On Edna Lewis, and Finding Your Own Path as a Southern Black Woman

Nicole A. Taylor is the author of Watermelon & Red Birds. Her words follow.

You can’t talk about American food, and you can’t be an American cookbook writer — Black or white — without having read or studied Edna Lewis. She’s an icon for her work as a chef and a cookbook writer but, on a very personal level, I feel so tied to her because she did the same thing I did: She left the American South and came to New York to do a thing. Many things.

For her, it was Freetown, Va., and for me, it was Georgia. She worked at a museum. She worked at restaurants like Gage & Tollner. She wrote cookbooks. And just like her, I came here to New York, and I worked for three nonprofits. I worked in retail for a hot minute. I wrote cookbooks.

When I look at Edna Lewis, she tells me that you don’t have to stay in a box. She tells me that you can take the foundation of being a Black woman from the American South and you can thrive in New York, and you can win in New York. This place is for you. You know you can create your own path and find your own tribe here.

For me, she represents more than just her work. She represents the idea that Southern Black women have a bigger story to tell beyond food, and that we’re not one thing. She’s a hero.

***

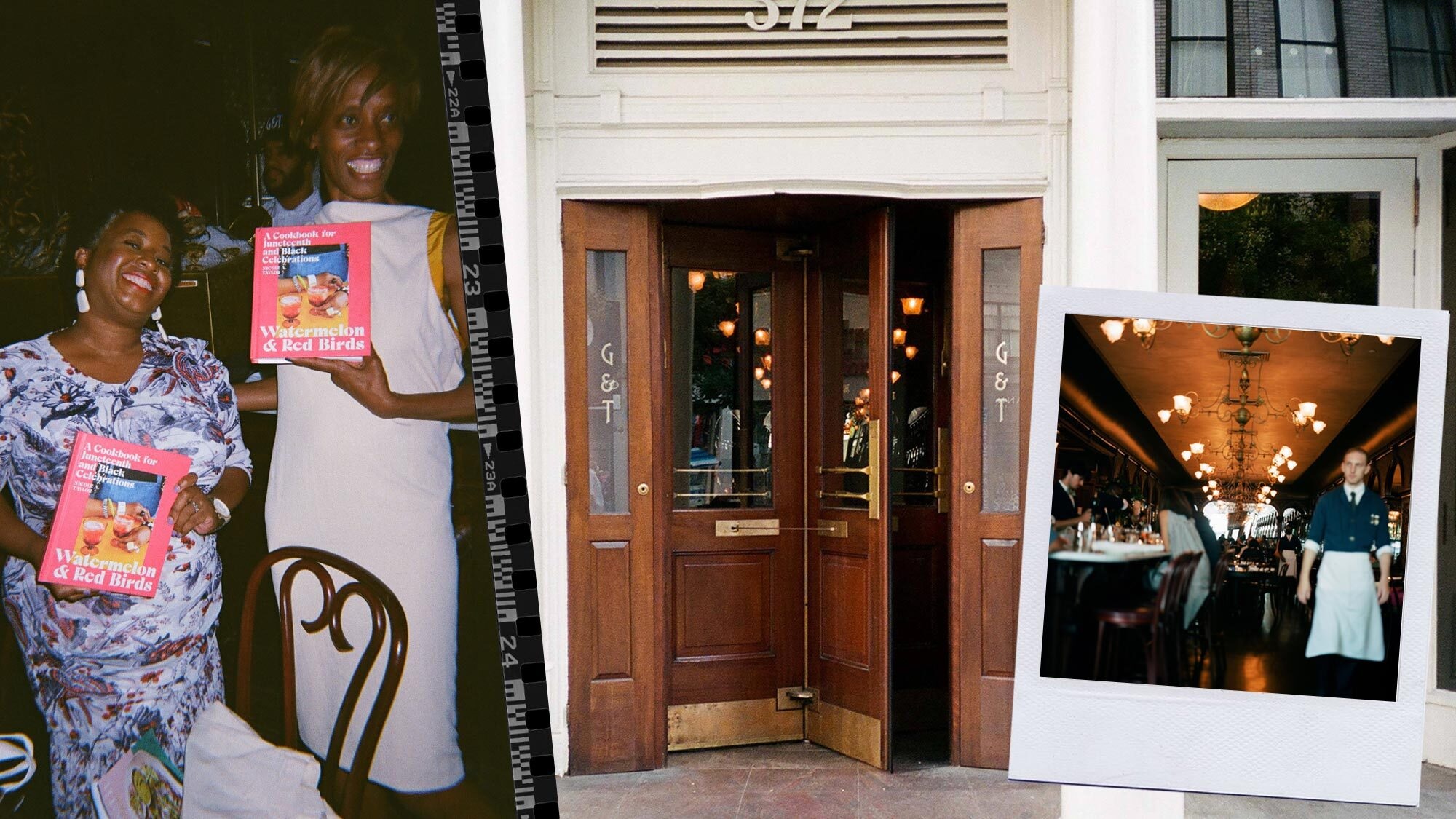

The first thing that hits you when you set foot inside Gage & Tollner is the light. There’s this beautiful light that floods over you — it made me kind of float a little bit. And the moment you enter the door, you see the postcards with Edna Lewis’ portrait at the host stand. There’s a private room upstairs named for her.

When we sat down and started eating, I kept thinking: Does this food taste like Edna Lewis’ cooking? Where is her influence? I saw it in the coconut cake, the fried chicken, and the yeasted rolls. Those dishes reminded me of her, and I wanted to know: Is this an Edna Lewis influence or is this a Gage and Tollner classic because it’s been here forever?

I searched high and low for a place that symbolized the cookbook, and Gage & Tollner was the one place I kept going back to. I first knew it because of Edna Lewis. I have all her first-edition cookbooks and, to go in there for the first time and to kick off my cookbook in a place where she worked and a place where her influence is still very present, it says everything about this moment. It’s the reason why I was in that place.

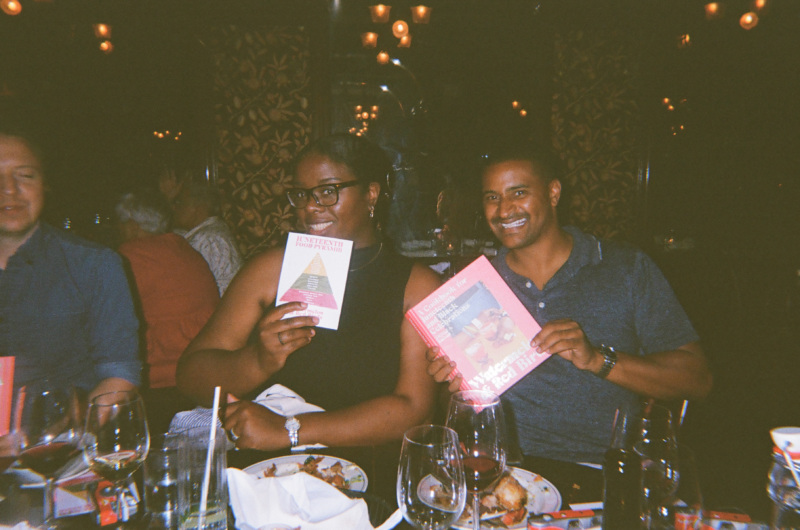

Yes, I’m a home cook, but restaurants feed me in more than just the plate. Going there was a way for me to reconnect with some of my closest friends and supporters, some of whom I was seeing for the first time since the pandemic.

For me, Edna Lewis represents more than just her work. She represents the idea that Southern Black women have a bigger story to tell beyond food, and that we’re not one thing. She’s a hero.

There was chef JJ Johnson — I was the first writer to write about him. There was writer Stephen Satterfield, the host of High on the Hog and the founder and publisher of Whetstone. There was my dear friend and writer Osayi Endolyn. There was Bon Appetit editor-in-chief Dawn Davis. This cookbook was the last book Dawn signed onto Simon & Schuster before she left to join Bon Appetit; she believed in the book before Juneteenth even became a national holiday. There was budding public historian Porscha Fuller, who explores Black foodways. There was Daniel Thoennessen, one of my favorite people ever, who interviewed me for his fried chicken documentary and we’ve become friends since. There was Aki Baker, whom I consider my spiritual adviser. And there was one of my best friends, Lesley Ware, one of my longest friends in New York, who happens to be a young adult writer herself.

I wanted to bring them all here to Gage & Tollner because I knew this was a place where I could celebrate; the menu speaks to what success means. Growing up, success meant T-bone steaks that mom bought whenever she got any extra money. The T-bone steak we all shared reminded me that you have to work really hard, and play harder.

More than that, too, it’s this whole idea of Americana. You can’t be a chophouse without a tower of oysters and shrimp cocktail or a wedge salad on the menu, but Gage & Tollner also shows you how this country and how restaurant culture have evolved. It’s having a kimchi salad served alongside the fried chicken, and serving tempura-style fried oyster mushrooms as another side. Those definitely reminded me of the fancy mushrooms recipe in the book and, in fact, so many dishes we shared mirrored recipes from the book, like the ribeye steak, the wedge salad, the fried chicken schnitzel. That amaretto coffee sundae and that baked Alaska — that baked Alaska reminded me of an icebox cake.

I saw Edna Lewis’ influence echoed even in the uniforms that the staff wore. I’ve seen many pictures of Edna Lewis, and I know how much pride she put into her very regal look. When I saw the impeccably dressed Black man behind the bar, I started to think about Edna Lewis and so many other Black staffers over the years: What does it mean for them to be working in a place that was the sh*t 40 years ago, and is back as one of the buzziest restaurants right now?

It made me think about evolution and, in a way, I think that applies to Black cookbooks, too. Black cookbook authors don’t have to define Black food anymore. That’s been done. I’ve been very privileged to help define what Black food is today and so now, when young Black chefs, or food writers, or home cooks want to enter into the space, they don’t have to start from that same point anymore as Edna Lewis did, or Bryant Terry did, or I did. They don’t have to define Black food because there are so many references at this point. They can dive right into creativity. We’re not in that box anymore.

I want people to know that Watermelon & Red Birds is a narrative cookbook with 75 recipes. There are recipes that I use to celebrate Juneteenth and celebrate other big events, and I use the African American table as a foundation. And not only did I use the African American food traditions as a foundation, but I also look to other cultures that have made America what it is and who stand with me, and who celebrate and commemorate June 19, 1865. You see a lot of influences from Mexican Americans and Latin Americans, from Indigenous Americans, and from Asian Americans. These are the foods that are at my table.

The whole time we were all at Gage & Tollner, I kept thinking: This is the good life. The good life means having 12 people around a table and everyone enjoying themselves. Nobody is worrying about what’s happening on the news, and nobody’s really picking up their phones. Everyone was engaging with each other.

And at that moment, I realized that this is why I wrote the book. I wrote the book to recreate that feeling, to give people a guide to make the same thing happen at their table. And a great restaurant, in my opinion, makes you feel like you’re at home. They feed you in more than just the plate.

Nicole A. Taylor is a James Beard Award-nominated food writer, master home cook, and producer based in New York and Athens, Ga., who has written for the New York Times, Bon Appetit, and Food & Wine. She’s written multiple cookbooks, including The Up South Cookbook and The Last O.G. Cookbook. Find out more about her latest, Watermelon & Redbirds, here. Follow Nicole A. Taylor on Instagram and Twitter. Follow Resy, too.

Nicole Taylor on Celebrating Juneteenth

Juneteenth is a Black holiday, but you can still celebrate Juneteenth if you’re not Black, too.

First, you need to acknowledge what June 19, 1865 is: It is the day that more than 200,000 enslaved Black Texans found out they were free, more than two years after Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. It’s a symbol of how we all want equality and freedom. We all want the ability for our families to live in America without being terrorized. We want them to have a better life.

It is important for all Americans to understand that very basic history about the holiday, no matter who you are.

And for non-Black Americans who are interested in Juneteenth and want to celebrate it and be a part of it, there are a few ways to do it. If there is a Black-owned restaurant in your neighborhood, and they’re open on Juneteenth, support them. Or gather people around your table and raise a glass to acknowledge Black American contributions to building this country.