Uyghurs in America Want to Share Food and Culture. For Them, It’s a Matter of Survival.

In May 2017, as Bugra Arkin neared the completion of his graduate studies in international policy and trade, he and his University of Southern California classmates visited Beijing to participate in a project with World Bank. Though Arkin was visiting his home country for school, as he tells it, Chinese government officials treated him as an enemy of the state. Armed police showed up at the hotel at 1 a.m. to scan his phone for prohibited apps and pepper him with questions, shocking his American professor.

When Arkin later visited his family in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang Province, he was ordered to come to the police station and held overnight — twice. “They asked very stupid questions: Why have you gone to America? What’s your goal?” he remembers. To secure his own release, Arkin promised them that he would come back to Urumqi after he completed his master’s degree at USC.

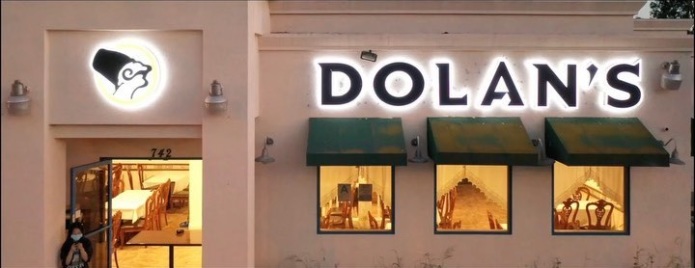

After graduation, it was clear that Arkin should not—could not—go back. He would make a living in Los Angeles. “I came up with this idea to promote our country,” Arkin now says. “I was going through a very hard, tough time. I thought, if I opened up a restaurant, it could somehow support my family. Americans barely know about us.” he recounts. In January 2019, he opened Dolan’s Uyghur Cuisine in Alhambra, Calif.

The idea that cooking the food of one’s homeland preserves and advances its narrative is hardly new. But when it comes to Uyghur cuisine, there is a particular urgency. The Uyghur people, indigenous to the Xinjiang region in China, have since at least 2017 been the victims of a campaign of ethnic cleansing by the Chinese government, one that both the outgoing and incoming U.S. secretaries of state recently called “genocide.”

And so well beyond the usual explorations of a lesser-known regional Chinese cuisine, Uyghur restaurants, and the food they serve, have become something more: platforms from which brave, exiled restaurateurs are advocating for their people. In these public spaces, they are not only able to be who they are, they are able to share their culture and religion with all who are willing to taste — and listen. As a cuisine, it is compelling: joining elements from central Asia and east Asia, all along the Silk Road that traversed Xinjiang, with rice dishes reminiscent of pilaf and pulled noodles that evoke Chinese lamian. Thus diners become entrusted with the aromas, flavors and beauty of a cuisine that belongs to a people that is fighting destruction in their homeland. And for these restaurant owners, such interactions are a way to defend their culture, and Islam, against eradication.

Xinjiang Province, in the far northwest of the country, is often described as an “autonomous region,” but sinicization efforts by the Chinese Communist Party have meant concentration camps, prisons, forced labor, forced sterilization and pervasive high-tech surveillance over everyday life — and COVID has only served as an excuse to further intensify these actions. Under the guise of battling extremism and separatism, Uyghurs are “re-educated” to renounce their culture and Islam. Hijabs are disallowed on women. Han Chinese clothing, reflecting China’s ethnic majority, is mandated, among many concerns . Many Uyghurs are forced to eat pork. Absolute control of the region is part of Xi Jinping’s larger plan for the Belt & Road Initiative, a huge infrastructure project that stretches from East Asia to Europe.

For the Uyghur people, there is no refuge from the horrors of a government actively working to demolish their culture and religion. Though life in the United States might be the embodiment of the American dream for those who can get here, many Uyghurs in the United States have described missing family and friends in Xinjiang. Arkin, for one, found out in December that his father had been tried in closed court for an undisclosed crime, without representation. His whereabouts, and the verdict of his trial, remain unknown. Arkin’s father, a publisher who went missing in October 2018, is one of over 1 million Uyghurs thought to be in camps and jails in Xinjiang, a number asserted by the United Nations, among others.

Abduhemit Abdukeyum, owner of the identically named Dolan Uyghur in Washington, owned an import-export business in Guangzhou before the Chinese government froze his accounts, forcing him into exile. “I cannot call my mother, my brother, my sister,” he says. It has been common for Uyghurs in China to delete and even block their foreign contacts from their WeChat profiles, so as to not give the government reasons to detain them.

Making any contact with loved ones back home can put those relatives in jeopardy. After moving here to attend school, Adila Sadir, owner of Silk Road Uyghur Cuisine in Cambridge, Mass., traveled to Turkey in 2015 to spend time with her father, who traveled from Urumqi to meet her. When he re-entered Xinjiang, the Chinese government confiscated his passport; eventually, he was detained in a concentration camp. “In 2019, my family got notice from the officials saying that my father got sentenced to prison for fasting,” Sadir says. “It’s a standard Islamic custom.” More than 30 of her relatives, including her 90-year-old grandfather have been detained.

▪️

Arkin’s Dolan, in the Chinese American haven of Alhambra, has become a dining destination for a diverse audience. It’s a testament to how skilfully he has perfected his recipes with Uyghur chefs and family friends Arkin Tuniyaz and Aziz Hajim. “Some people ask me, ‘How dare you open a Uyghur restaurant when you only have a thousand Uyghurs [in Los Angeles]?’” says Arkin. “And I respond, ‘I’m not open for the Uyghur people; I’m open for Americans. Everyone can eat Uyghur food.” Despite the pandemic, he says, business is good. Customers often drive from all parts of Los Angeles to eat there; after COVID hit, Dolan has more often thrived thanks to takeout and its use of multiple delivery apps.

For the uninitiated, Uyghur food can be an enigma. Arkin describes his food as “fusion,” which is apt; the Uyghurs are a Turkic-speaking, Muslim people. The historic Silk Road ran through Xinjiang, connecting east and west, and you can taste this passage from one continent to the other in the food. Cumin, Sichuan peppercorns, star anise, black pepper and cardamom season these halal dishes. And there’s often less sauce in Uyghur food compared to other Chinese regional cuisines.

When new diners try these dishes, Arkin says, “some people ask me, ‘How did you invent this food? It has some Chinese influences, like noodles, but you have samsas [triangular stuffed buns], kebab skewers and other pastries.’ They thought I invented the food here. But I tell them, ‘No, this is how Uyghur food is. We’ve been around for 2,000 years.’”

At Dolan, wheat noodles known as laghman are folded, pounded, rolled and stretched by hand many times, before the long, round threads are stir-fried with green peppers, onions and beef. Sometimes the noodles are diced into half-inch snippets, ensuring a spring to that elusive quality known as QQ. Chunks of juicy braised lamb adorn polo, Dolan’s primary rice dish; and the restaurant’s manta, or dumplings, are the size of a baby’s fist and filled with ground beef and onion. Interestingly, you can also listen for the continental crossover in the roots of each dish’s etymology—comparing samsas with sambusas and samosas; laghman with lamian and ramen; polo with, well, more polo and pilaf; manta with mandu.

▪️

Uyghurs who have managed to find asylum in America still feel a threat. Often they’re torn between speaking out to shed light on injustices back home, and the possibility that their protest will make their families targets of intimidation, or incarceration. But these business owners also know that their restaurants can serve as an effective platform.

“I think I have to talk about the killing,” Abdukeyum says, “And many people who love Uyghur food ask about the culture. I am very happy to talk; I have enough money, and money is not a very important goal—all my accounts in China were frozen, anyway. Talking about Uyghur genocide is very important.”

For Sadir, the desire to speak out had to be mulled against the risks of endangering her father: “When my father disappeared, I struggled for three or four months deciding whether I was going to speak out on social media or not. But I thought, if I don’t speak up for my father, he might be dying in some concentration camp, you know? So I choose to stand up for him.”

As mass detainments have increased, and surveillance has reached record levels, governments have increasingly concluded that international pressure is the only way to curtail China’s human rights abuses. But it’s not simply China’s role as a political superpower; it’s also its mighty business interests that remain a major obstacle.

Arkin is hoping that increased awareness here will put more pressure on China. And dining is a tactile way to make a connection in the real world. “Food is a very good bridge to link people with Uyghur culture,” he says. “People come because someone they know liked it. When they come here, they eat our food, drink our tea and watch videos — they ask me questions and I explain to them everything [that’s going on] with our people … We always have TV screens [looping videos] of our culture, our music. So they start learning about Uyghur culture and start to understand it.”

In Urumqi, meantime, the situation keeps getting worse. Arkin had received a phone call from his mother in Urumqi, who had been intimidated by authorities after the Los Angeles Times ran an article on his father’s detainment. “They visited my family every week,” he says. “They threatened my mom, and tried to convince me to show my loyalty to the Communist party of China. I have a videotape of that Facetime with China, and it’s unbelievable. It’s crazy. And I’m here. I’m in the U.S. but I’m still feeling the threat from them. Even here, I don’t have as much freedom as you do.”

A selection of Uyghur restaurants around the country:

Dolan’s Uyghur Cuisine: 742 W. Valley Blvd., Alhambra, Calif., 626-782-7555, ladolans.com.

Silk Road Uyghur Cuisine: 645 Cambridge St., Cambridge, Mass., 617-945-1909, ordersilkroad.com.

Dolan Uyghur: 518 Connecticut Ave. NW, Washington, D.C., 202-968-2010, dolanuyghur.com.

Nurlan Uyghur Restaurant: 43-39 Main St, Queens, N.Y., 347-542-3324, nurlan-ny.com.

Caravan Uyghur Cuisine: 200 Water Street, New York, N.Y., 917-261-7445, caravanuyghur.com.

Kusan Uyghur Cuisine: 1516 N. 4th St, San Jose, Calif. 408-899-4365, kusancuisine.com.

Esther Tseng is a food, drinks and culture writer. She has contributed to The Los Angeles Times, Eater, Food & Wine, Civil Eats and more. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram. Follow Resy, too.