Packet by Packet, This Duck-Sauce Dynasty Forges On

Individual restaurants come and go, but the soy sauce packet is forever. And if you live and eat lo mein in the tristate area, there’s a good chance that soy sauce packet was made on the factory floor of WY Industries—formerly the Wah Yoan Condiments Products Corporation—in North Bergen, N.J. They’ve been at it since 1977. And little about their hydrolyzed soy-protein-based soy sauce, or its single-serving plastic film container, has changed since then.

That is not the case for WY, the company, whose last appearance in the public eye was in 1994, when the New York Times profiled the business and its success as part of the “still growing national preference for portion-control packaging that has accompanied the explosion of takeout food in recent decades.” Today WY produces over 1 billion sauce packets a year, and hundreds of millions of takeout containers. Those numbers don’t even include the food-service ingredients they produce in bulk: the primordial elements of a million beef-with-broccoli combo meals. If you’ve ever wondered what gives a takeout restaurant’s barbecue pork ribs their crimson hue, it’s products like WY “tomato color.” Your favorite stir fry with brown sauce may begin with a glug of WY’s “thick sauce,” a mix of blackstrap molasses, corn syrup, salt, and food colorings.

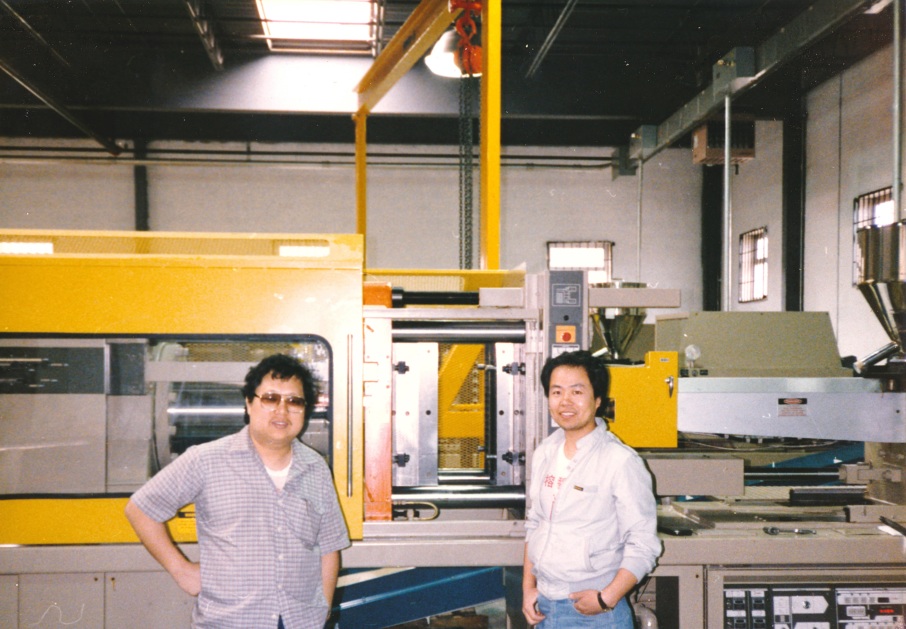

Cofounders (and brothers-in-law) Bill Cheng and Nelson Yeung were not the first to get in on the packet game, but they thought they could do it better. After all, they had a van. “We’d drive around to local restaurants all around us in New York,” Cheng tells me over a video call, joined by longtime staff and members of his family who also work at the company. “Back in the ‘70s, there were already some duck sauces and mustards, but we wanted to make a better product.” As the company’s only employees at the time, Cheng and Yeung brewed and cooked the sauces, packed them, and made sales calls and deliveries all on their own. And just why, I this writer asked Cheng, is a sauce made of pulped apricots, corn syrup, garlic, and onion called “duck sauce” if it’s almost never served with duck? “That question,” Cheng replies with a chuckle, “is before our time.” (Culinary historians theorize it’s a distant descendant of a sauce made with tart plums native to China, but we digress.)

The men tinkered with their soy sauce recipe in small batches—a little salt here, some more sweetener there—until they developed a product that found quick commercial success among the booming Chinese restaurant industry. Said industry has always had to design its menus around the palates of its white clientele, which is as much a science as an art. Even in an era where it’s easy for restaurants to import rare specialty ingredients from China, the customer wants what the customer wants, and there’s no substitute for the taste of American Chinese takeout.

Some bulk products, like that thick sauce, were part of WY’s initial portfolio. Considering how many restaurants it’s used in, across so many dishes with so much cultural resonance, you could easily place Cheng and Yeung alongside Clarence Birdseye and Ben Cohen & Jerry Greenfield as foundational 20th-century architects of American flavor.

After all, there are an estimated 46,000 independent Chinese restaurants in the United States, three times the number of McDonald’s locations. Think about your platonic takeout fried rice; would it really evoke the same comfort and nostalgia without the Pantone specificity of its sunny yellow glow? It’s products like WY’s “egg shade” that make it possible.

However these days, the company is looking to expand beyond the Chinese restaurant market.

“In the ‘70s, you had lots of Chinese immigrants coming to the U.S. and setting up restaurants,” says , says Chen Zhang, Bill’s daughter in law and a manager of sales and marketing in charge of new business. “But their children don’t necessarily want to continue those restaurants, so it’s not the same setup anymore.” Then there’s the issue of consumer demand. “American tastes are changing. More Asian fusion and Asian inspired cuisine. So we have to adapt and make sure we’re getting the right base of customers.”

As for what those adaptations will look like, Zhang prefers to keep those cards close to her chest. One topic she and the team are all too happy to discuss is the company’s sustainability initiatives, which head mechanic Brian Buchalski describes less as a do-gooder marketing stunt than a necessary part of doing business. “In the ‘70s and ‘80s, your green footprint was an afterthought,” says Buchalski, who has been with the company since 1977. “Now it’s your primary thought. You can’t run a factory while using that much hydraulic oil and expect to be profitable.” Sustainability is of course a complicated subject: Just 10% of the plastic used in WY’s soy sauce packets comes from recycled materials, but the company has reengineered its assembly line to reduce emissions and waste, adding energy-efficient lighting, replacing gas-guzzling hydraulic motors with servo technology, redesigning containers to use less plastic. When WY installed rooftop solar panels in 2005, they were the largest solar installation in New Jersey.

Buchalski is far from the only longtime employee who’s stayed at WY through the years; roughly a third of the company’s 100-plus staff have been there more than a decade. Beyond that, six members of the extended family currently work at WY.

As the restaurant industry continues its scrambling pivot to takeout, outdoor dining, and disposable dishware, the future of the soy sauce packet looks bright. That’s something to feel good about. Like the “We Are Happy to Serve You” coffee cup before it, the single-serve soy sauce packet is an enduring artifact of American restaurant culture. And while there’s no such thing as a bulletproof business in food service, the WY team is planning for the long haul — and to keep it all in the family.

“I’m nearly 70,” Bill Cheng says. “I’m still young.”

Max Falkowitz is a food and travel writer from Queens. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Food & Wine, and other outlets. He’s also the co-author of The Dumpling Galaxy Cookbook with Helen You. Follow him on Twitter. Follow Resy, too.

Discover More

Stephen Satterfield's Corner Table