Lessons in Closure, Or, Never Take Chinese Restaurants For Granted

Those of us who eat out for the sheer joy of it will always have a short list of Chinese places we return to year after year — and sometimes even week after week.

But time, compounded by the economy and then multiplied many times over by the pandemic, changed all that. Boarded-up Chinatown and suburban restaurant windows are now covered with graffiti, their entrances filled with whirling bits of trash. And yet we walk past them still, muttering our condolences over their ever-worsening appearances and hoping against hope that they’ll one day return.

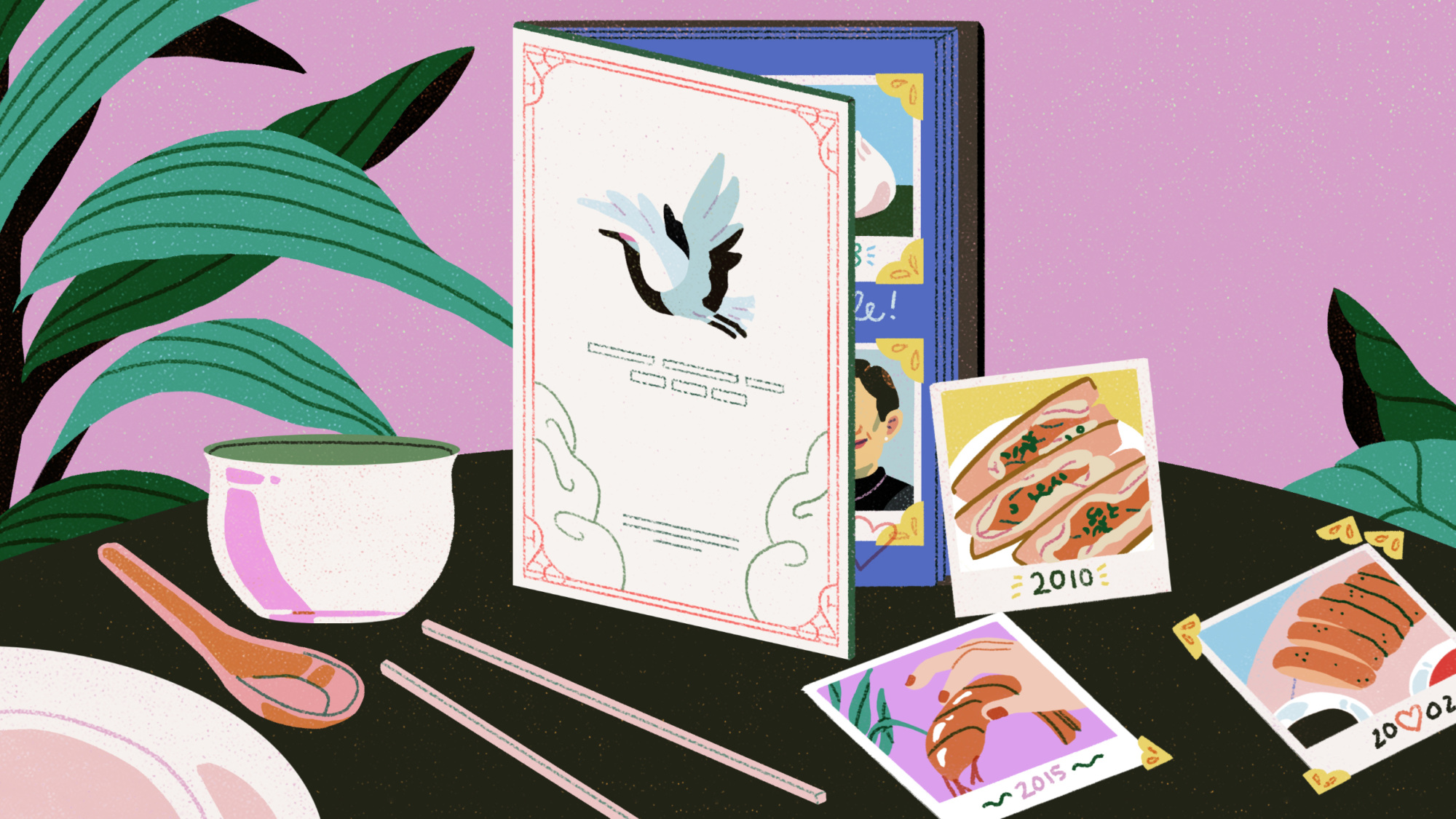

The shuttering of a beloved restaurant is, as far as I am concerned, the death of a good friend. And so I continue to grieve in my own weird ways. I stuff my dogeared, spattered menus into a scrapbook folder, but first I longingly scrape at their spatters, as anxious as a junkie for that one last hit. I Google pictures of my Bay Area go-to restaurants and their foods. I search Instagram accounts for the backlit, adoring food-porn shots I would have ignored in other, happier times. I find myself thinking back on all the great dishes, familiar faces, and delightful smells I took for granted not so long ago.

We used to visit places like Little Sichuan in San Mateo so often that we knew the waitresses by name, the menu by heart. Its affable owner Jimmy would personally deliver samples of whatever new dishes he was trying out to our table, proudly auditioning them before adding them to the menu. And then we stopped going because we moved too far away. And then they closed. And then I try to tell myself that it was not my fault, for who knew any place so good could disappear in a flash?

Like the sound of my mother’s laugh, so many of the places we often dined at lost their foothold in this world and now are relegated to the slipstream of my past. And yet, my nose still can recall the scent of a braised duck on its short trip from the kitchen to the table at San Francisco’s Jiangnan Cuisine and how it mingled with the oohs and ahhs of customers as it floated past the other tables. Or the sparkle in my husband’s eyes when we sat down to meals at Ton Kiang on Geary Street and ate all the dishes there that reminded him of his late Hakka father’s cooking. Ton Kiang had been around for 42 years, long enough to qualify as a San Francisco institution, and I was pretty sure it would be serving its uniquely savory dim sum forever. Now we’ll never taste them again.

It wasn’t only COVID that changed our culinary landscape. Oftentimes, all it took was the felling of one person. My husband reminisces to whoever will listen about how chef Yu-Lin Liu always welcomed us to our table at Cupertino’s Ho Ho Restaurant with a delighted chuckle. He referred to himself as our “imperial chef” because he would cook up whatever we wanted, even if it was off menu, after sending his tiny prep cook — a feisty drunk who looked and talked like a Cantonese pirate —to hit up the Chinese supermarket next door for whatever was required. My favorite was the chef’s stir-fried wharf noodles (chao ma mian), a comforting, sweat-inducing basin of brick-hued soup, a hybrid Shandong-Korean creation that no one else has ever equaled in my book. It haunts my dreams even now with its perfect balance of chile-inflected stock, slithery noodles, sweet shrimp, and buttery calamari.

At our last dinner there, chef Liu complained of a sore knee, and the next day was struck down in front of his stove by a massive heart attack. With a start, I wonder what ever happened to his wife who kept the books, to the slow son who clung to his mother at twenty as if he were still five, to the older children who dreamed of careers far away from the drudgery of their family’s restaurant.

My husband and I had once tethered our lives to all these places that we went to on a regular basis — a tether that the years and this pandemic incessantly gnawed at until we are left with only fading recollections. I mourn as I try to remember the details of the hand-painted wallpaper that decorated another restaurant’s wall for decades, the one smeared with oil and fingerprints over the bottom six inches. Or that place with the whiteboard covered in scrawled Chinese and advertising Today’s Specials, even though it never changed in all the years we went. Or the one that with that damned flickering fluorescent light, an irritant that I would happily give a lot to dine under one last time.

▪️

We should have drawn

the owners aside to express

our appreciation for all of

the hard work and experience

and sacrifice that went into

each dish.

▪️

My experiences in Taipei should have taught me better. Back in the late 1970s and early ’80s, Taiwan’s greatest chefs served up tastes of regional cuisines that by that time existed nowhere else on Earth. Most of those who cooked for the high and mighty on the mainland fled to Taiwan in 1949. This eventually allowed perennially hungry folks like me to dine on unimaginably delicious things when those chefs finally emerged from their private kitchens and opened up places of their own in downtown Taipei. Like chef Liu, they poured their homesickness and primal hunger into sandpots and woks just so we could walk away from yet another perfect meal feeling as if we had visited their hometowns for a few short hours. It was time travel disguised as dinner.

Some days we were treated to the specialties of a particular region’s haute cuisine, like Beijing’s refined imperial dishes, or Jiangsu’s sublime culinary inventions from the Huai Yang area or the Tan Family’s exquisite interpretations on Cantonese gastronomy, while on others we shivered with delight over some simple yet inspired meal. Concepts and ingredients with no equivalents elsewhere on this planet spoke to me of centuries upon centuries of people mulling over what should be served that evening. Food opened the door for me to China’s many cultures, to places I had not yet visited, and so I once imagined Changsha as being forever wreathed with the aroma of smoky charcuterie, Fuzhou as steeped to its collective eyeballs in scarlet rice wine, and Shunde as tasting of a strange but delicious combination of deep-fried milk and steamed grass carp.

Also Read: How to Have a Lunar New Year Feast, Wherever You May Be

We returned to Taiwan many times over the ensuing decades. And yet, one by one, our favorite restaurants closed and their acclaimed chefs passed on. A handful of places still managed to hang in there for a few miserable years under younger head chefs, but the food they served became unrecognizable. Gone was that flash of genius, that respect for the ancient ways, that love for perfect ingredients. Instead, bland dishes were set before us, decorated with caviar, foam, orchids. Tiny holes-in-the-wall that had once created temple-style Buddhist dishes now offered the same cheap pizza and dumbed-down Sichuan hotpot as every other place in the alley.

We would sit down with our Taipei friends over instantly forgettable meals and ask them: Do you remember that Chaozhou feast, the one that featured steamed razor clams spangled with fermented black beans and chiles? Or the enormous braised prawns at the Tianjin restaurant on the east side of town, where we ordered plate after plate of flaky grilled breads just so we could mop up the sauce? Or that time we ate Peking duck the old-fashioned way on Zhonghua Road, at a feast that lasted for hours, starting with a steamed duck-egg custard and ending with a savory soup made from the bones? Or that shop with fifty flavors of homemade ice cream, including mustard and pork floss and plum wine, and how we would attempt to create silly meals out of them? We laughed and we laughed, and we shored up our memories. And then we grew silent and sad. With each passing year, we found fewer reasons to return, to eat, to revisit the past.

So, we should have known better. We should have taken every opportunity to tell those cherished restaurants we frequented here in the United States how they were more than mere places to eat. We should have drawn the owners aside to express our appreciation for all of the hard work and experience and sacrifice that went into each dish, into everything that they cradled between their hands on the short walk from the kitchen to our table. How they had become part of our lives. How they had fed our bodies and our happiness. How they had made us feel welcome and safe and warm.

But, fickle lovers that we are, we didn’t know what we had until it was all too late.

Carolyn Phillips is an artist and food scholar, and the author of “At the Chinese Table: A Memoir with Recipes,” “All Under Heaven,” and “The Dim Sum Field Guide.” Follow her on Twitter and Instagram. Follow Resy, too.