Community Series Washington D.C.

On Being Queer, Arab American, and Speaking Truth Through Food

Silver Spring, Md. native Marcelle G Afram is the chef and owner of Shababi in Washington, D.C. They previously worked at restaurants that include Maydan, Compass Rose, and Bluejacket. Their words follow.

In the last few years, I’ve realized that what I want to do for the rest of my life is to cook the food of my people. Before, I felt like I wasn’t talking about the Palestinian narrative of who I am as a person enough, and that’s when I had the idea of doing Palestinian-style chicken.

In the last few years, I’ve realized that what I want to do for the rest of my life is to cook the food of my people. Before, I felt like I wasn’t talking about the Palestinian narrative of who I am as a person enough, and that’s when I had the idea of doing Palestinian-style chicken.

I opened Shababi as a pop-up this January at a friend’s deli in Alexandria, Va., and now, my wife handles the front-of-house operations, and my son is my sous chef. We make Palestinian rotisserie chicken that we brine for a whole day, and then coat with a musakhan-inspired mix of spices that includes allspice, sumac, cumin, fenugreek, and cardamom. I see us on the path to being a brick-and-mortar by early next year.

- New York Has Incredible Mexican Food. Here’s Where to Find It.

- ‘We Are Still Here’: On Standing Up for San Francisco’s Black Community

- Hmong Food Isn’t a Cuisine. It’s a Philosophy.

- On the Resilience of Long Beach’s Cambodian American Community

- On American Barbecue and the Black Community That Built It

Shababi has just been this wonderful platform for me to tap into a part of who I am, of being Palestinian, that that has often been discouraged throughout my life. It lets me pay homage to my grandparents, and to all of us from this marginalized group of people who don’t have nearly enough representation for who we are as a people.

I’m able to draw from all these taste and food memories that I have from my own family — like my maternal grandmother’s stuffed sausages, or my grandfather’s fire-roasted fish, rubbed with sumac and cumin and stuffed with orange slices, spicy chile paste, and tahini. I frequently go to my mom as a reference, to ask her about some of the food ways that we grew up with. And I’m taking those memories and recipes and reinterpreting them.

While cooking the food of my people is also personally enriching for me, I also see it as helping build a community, too, both for Arab Americans and especially for Queer Arab Americans like me.

▪️

Coming out as transgender last year is the greatest thing that’s ever happened in my life, and there’s been a lot of really great things.

For most of my life, I thought I was a lesbian, and a woman, and accepted that to be my truth, because I didn’t realize there was an expansive way to understand my gender, and that it was different than sexuality. But once I realized that there was a space for transmasculine and non-binary people within the transgender community, it felt like a rebirth. I was finally able to understand who I was, in a capacity that I never knew existed.

Before, I was in a lot of pain. I felt so isolated. I never really felt seen, both as an Arab American, and as a Queer person.

And while visibility isn’t everything, I’ve realized that visibility for marginalized peoples in spaces that we haven’t occupied in the public eye is so important as a foundational building block, and that lack of visibility in my life has definitely shaped who I am as a person.

Before, I didn’t know how to connect myself to an Arab community; I was scared because I didn’t know if I’d be accepted. And within the Queer community, I didn’t feel like I was fully accepted for who I was because I couldn’t really relate to others who identified as lesbians. I was misconstruing my gender identity for sexuality, and I just felt really alone.

But I’m not alone. There’s a whole community of people who, like me, identify as Queer and Arab American, and who have felt like we didn’t fit in, or that we were outsiders. That we didn’t have safe spaces where we could feel supported.

▪️

“For Arab Americans, there’s always this pressure to be this model immigrant community, but post 9/11, there was a major shift — there was this added element of fear, and this consensus that we just don’t talk about who we are.”

▪️

But that’s changing now. And a big part of that change is being driven by us, by us being able to navigate our own spaces with our own voices. Here’s mine.

▪️

I loved growing up where I did, in suburban Maryland. My family owned small mom-and-pop businesses, like sub shops that also had some Middle Eastern food on the menu, throughout the D.C. area.

I actually started working for my parents when I was 10 years old. I was always getting into trouble at school and so my parents said, “Well, you’re going to start working now.” Looking back, I wonder if it really was because I was always in trouble or whether I was free labor, but regardless, it was probably one of the best things that had ever happened to me. It allowed me to immerse myself in something that I started to love, which was food, and it made me feel connected to my family, and to my Arab culture.

When I try to explain my family history, it can get a bit complicated, because so much of it is shaped by diaspora from forced displacement. A few of my great grandparents, who are Syriac Assyrians, came to Palestine in the late 1800s and early 1900s because they were fleeing persecution and genocide in northern Syria and southern Turkey. That’s where they integrated with the Arab and Palestinian side of my family. And my grandparents on both sides later fled Palestine in 1948 during the Nakba, when they were forcibly removed from their homes. My mother’s family went to Lebanon, where she was born in Beirut, and my father’s family went to Syria, where he was born in Damascus. My mother’s family immigrated to New Jersey in the early 70s, and my father’s family came to Maryland at that time.

I’m the oldest of four. Growing up, we were very involved in the Syriac Orthodox Church. We spoke Aramaic, and we prayed in Aramaic at church. My grandparents spoke Aramaic, but we spoke Arabic and English at home. Arabic was my first language. Sometimes, I felt like we led this dual life and there was this dichotomy that my parents struggled with: Like they taught us to be really proud of our heritage, culture, and religion, but they also told us not to tell anybody. “When people ask you what you are, you say you’re ‘American.’”

They started sending me to this expensive private Catholic school in the third grade that they saved up all their money for, and when I was there, I’d always get asked, “Where are you from?” When I told them I’m American, they still didn’t understand, because I looked different from them. I ate differently. I spoke languages they’ve probably never heard of.

At the time, I felt like I was lying, but now I understand. It was about survival.

Our family has been persecuted for centuries, and at some point, that kind of thinking just gets ingrained into who we are. So even as diverse as suburban Maryland was, I don’t think that I really ever found a way to express who we are ethnically, in a way that fit into what was around us.

I left home when I was 17. My parents had hoped I might marry into the Syriac community, but I knew that path wasn’t for me. My mother was on her way back from visiting my grandmother in New Jersey, so I wrote a letter to her and left it under a pillow. All it said was, “I don’t think this is right for me right now.” My father found the note, and he said that if I wanted to be this way, I could be this way on the street. He didn’t say, “get out of the house,” but I took it like that at the time, so I left. And I didn’t speak to my family for 11 years after that.

Those 11 years were tough, but I also learned a lot. I basically went into survival mode, and I spent much of those years homeless, finding shelter with friends, or in shelters, and sometimes parks. But I knew that I needed work to support myself, and the only thing I really had experience in was restaurant work.

I wound up at the Irish Inn in Glen Echo, Md., and it was my first real experience with a full-service restaurant, and it just blew my mind. I started there as a food runner, and worked my way up to expo, and there was one night when the fry cook just walked out in the middle of service, so I stepped in. It was the worst service in my life; I had no idea what I was doing. But I kind of loved it, and knew I wanted to do this.

At some point, I found myself cooking in Spain, and eventually I wound up on the island of Mallorca where I worked on a fishing boat that fished for octopus. After saving up some money, I decided it was time to come back to the States and started cooking at restaurants in the D.C. area, while also working at a farming co-op in Wisconsin, and even a hotel restaurant in Puerto Rico. In 2006, I decided to finally settle down in D.C. and, three years later, while working at Zola Wine & Kitchen, I met my wife, who was a general manager.

My wife, Joyce, was actually the one who helped me rekindle a relationship with my family. She reached out to my mother and now, we’re in a really good place. My family has been super loving and accepting of my wife and our son, Caleb, whom they’ve now known since he was 9.

Last year, when I realized I’m transgender and was about to start my hormone therapy, I came out to my sisters first and then, reluctantly, my parents. But honestly, I don’t think I could have expected the response I received from them: They said that they loved me, and I know what’s right for me, and as long as I’m safe and not hurting myself, they were there for me. They would always be there to support me. It was huge. I’ve always been really scared of disappointing them and that’s partly why I didn’t attempt to connect with them all those years.

Over time, I’ve realized what my parents are most scared of is other people hurting me. Through all of their protections and their strictness, it just comes down to that. When you’re talking about a community of people who have been fleeing this decimation of their existence over and over, and over again, that’s just a really natural response to things.

They still don’t always get my pronouns right, but they’re working on it. But we’re in a really good place, honestly, and I am so happy.

Some of My Favorite Spaces in the D.C. Area

Putting this list together has made me realize the obvious need that D.C. has for Queer Arab spaces and I hope that I can, in the near future, impact that. D.C. is known for being this inclusive, progressive, and diverse city, but there is still a lot of work to be done to create specifically inclusive spaces for marginalized peoples. I would love to see the city empowering and creating opportunities for Queer BIPOC to have accessibility to more general ownership in these spaces, and specifically restaurants.

These are a few places that really stand out to me as a member of the Queer Arab community.

Busboys & Poets

Busboys & Poets is an iconic local establishment with multiple locations owned by philanthropist and social rights advocate Andy Shallal. The programming at his establishments that focus on marginalized communities and social rights is so extensive. One that stands out most recently is a poetry reading by local Palestinians in the diaspora that helped raise funds for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency.

I found out that I have both a gluten and dairy sensitivity in 2020, so I try to limit my intake of both. Busboys & Poets has an awesome selection of gluten- and dairy-free options on their vast, diner-like menu. The sweet potato flatbread pizza is my favorite of the options; the dough is crispy, salty and sweet, and topped with seasonal vegetables. Multiple locations, including 2021 14th St NW, Washington, D.C.

DC9

DC9 has been a long-standing inclusive space. I used to find a lot of solace going there in my 20s, when I was trying to find my footing in my existence, and it was the perfect place to find some great live music or local DJ playing, and has always had some really solid bar food, too. The burger menu at DC9 is out of this world! There’s no bad choice. I’m a sucker for deviled eggs, and the ones here can’t be missed. 1940 9th St NW, Washington, D.C.

The Green Zone

The Green Zone is an amazing bar and restaurant in Adams Morgan that really focuses on being a classic, comfortable, and inclusive place, especially for those of us from the community. I know for a lot of us it gives us that sliver of community and home that is hard to find in a restaurant setting. I love their classic dishes, showcased from the Arab-speaking world, especially the kubbat halab, which is ground lamb and beef in a crispy rice shell, and the mana’iish, a sourdough flatbread topped with za’atar that’s always a go-to. Although they’re a bar, and I don’t drink alcohol, they have many great non-alcoholic beverages; my favorite is the mint lemonade. a frozen slushy of pureed fresh mint and fresh squeezed lemon juice. 2226 18th St NW, Washington, D.C.

Z&Z

Z&Z are known for their excellent za’atar that comes directly from Palestinian farmers, but they also crush the manoushe game. They can be found at different farmers markets through the region making their beautiful manoushe on a traditional saj. They just announced that they are opening their first brick-and-mortar restaurant in Rockville, Md., in the near future, and I couldn’t be more excited. 1111 Nelson St, Rockville, Md.

Some other places I love, run by people who are impacting the Washington, D.C. area in a positive way are:

Compliments Only Subs

The best subs in the city. Simple, classic, full. They just started offering gluten-free bread which is a nice touch. Pro tip: Grab some of their tuna salad in an 8-ounce serving and a bag of Utz, and you’ve got yourself a great on-the-go snack. 1630 14th St NW, Washington D.C.

Money Muscle BBQ

My favorite barbecue: no frills, just delicious, and perfectly executed. The smoked wings with the dry rub are my absolute favorite. 8630 Fenton St, Silver Spring, Md.

Oyster Oyster

Chef Rob Rubba has taken sustainability to a level that we can all aspire to. One of the best dining experiences in D.C., and a vibrant approach to vegetable cookery that is mind blowing. 1440 8th St NW, Washington, D.C.

Rasa

I love this local quick-service restaurant. Go for the bowls, but don’t miss out on the soft-serve options; the last one I had was a soft-serve mango lassi that was incredible. 1247 First St SE, Washington, D.C.

Thip Khao

I ate at Thip Khao a couple times a month when COVID-19 first shut everything down in 2020. The Laotian food by chef Seng and chef Boby had always been delicious, but there was something especially heartwarming and satisfying about being able to order it during that time. The khao poon, a red coconut curry with rice vermicelli, is the most soul-soothing dish. 3462 14th St NW, Washington, D.C.

Silver Spring, Md. native Marcelle G Afram is the chef and owner of Shababi. Follow them on Instagram.

Resy Presents

The Community Series

-

New York Has Incredible Mexican Food. Here’s Where to Find It.

Taco Literacy professor Steven Alvarez gives us his personal tour of some of the city’s best Mexican restaurants, and the stories behind the people who run them. -

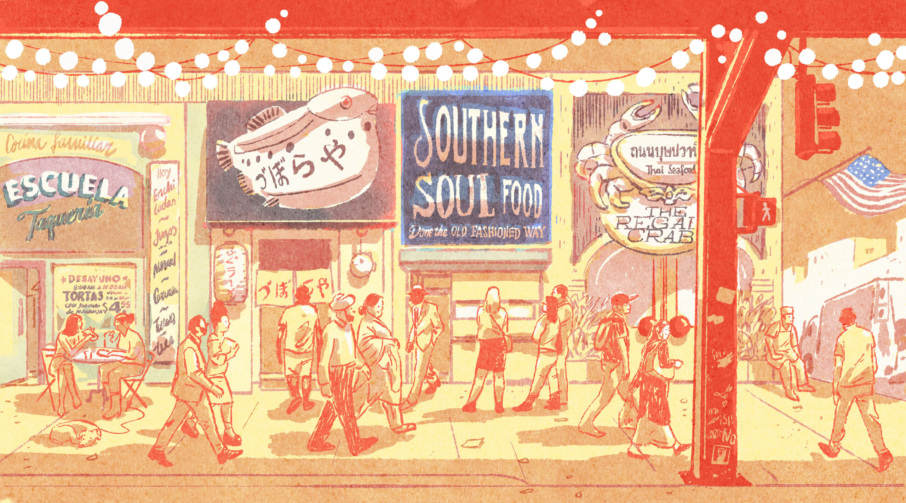

Because This Is What Community Looks Like

Welcome to Resy’s Community Series, a celebration of the people and places that make our communities special, told through their own voices and perspectives. -

‘We Are Still Here’: On Standing Up for San Francisco’s Black Community

Chef and San Francisco native Tiffany Carter on fighting to preserve African American culture, and her guide to eating your way through her hometown. -

A Chef’s Eating Guide to the Twin Cities’ Hmong Village

Follow Hmong American chef Yia Vang on a tour of his favorite stalls at Hmong Village, a sprawling indoor market and the epicenter of Hmong cultural life in the Twin Cities. -

A Local’s Guide to Eating Your Way Through Long Beach’s Incredible Cambodian Restaurants

Follow Cambodian American food content creator James Tir on a tour of his hometown favorites. -

On American Barbecue and the Black Community That Built It

Food historian Adrian Miller doesn’t remember how old he was when he started craving his mother’s barbecued pork spareribs. But he knows it was love at first bite.