On American Barbecue and the Black Community That Built It

Food historian Adrian Miller doesn’t remember how old he was when he started craving his mother’s barbecued pork spareribs, sausages, burgers, corn, and other goodies.

Food historian Adrian Miller doesn’t remember how old he was when he started craving his mother’s barbecued pork spareribs, sausages, burgers, corn, and other goodies.

But he knows it was love at first bite.

“The taste of grilled meat, the smell of it, the sauce — it’s just different from what you’d normally get,” Miller says.

Three times a year — on Memorial Day, Fourth of July, and Labor Day — up to 15 of Miller’s family members descend upon the Denver suburb where he grew up to sink their teeth into his mother Johnetta’s barbecued cuisine.

Building on this love of his mother’s cooking, Miller wrote a new book, “Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue.” It details the foundational and essential contributions Black barbecuers, pitmasters, and restaurateurs made to barbecue, which has since become a cornerstone of American life.

- The Resy Community Series

- Soul Survivor: The Story of the World’s Oldest Soul Food Restaurant

- A Louisville Community Kitchen Aims to Heal a Divide. Its Best-Known Chef and a Rising Star Are Behind It.

- The Layered Legacy of Roscoe’s House of Chicken & Waffles

- Original Soul Vegetarian: Proof That Divine Culinary Inspiration Can Grow on Trees

- For Black People Eats Founder Jeremy Joyce, Helping Black Restaurants Is Everyone’s Job

Researching the history of American barbecue showed Miller how important barbecue has been in terms of building communities throughout the U.S. He says politicians and preachers were the first community leaders to realize that cooking whole animals drew crowds to do the prep work, cook, serve, eat the food, entertain each other, and socialize. Barbecue fueled the political rallies and church functions that drew hundreds to thousands of people.

And by the turn of the 20th century, Miller says, African American barbecue restaurants were building community in different ways as well. During segregation, they were a welcoming space when Blacks had few options for dining out. Black barbecue restaurant owners also carried on a long legacy of offering affordable menu items for low-income customers and giving out massive amounts of free food to the public on holidays and to social justice activists working in the trenches.

Miller says his book not only celebrates African American barbecue culture, but it also restores Black Americans to their rightful place in an American barbecue narrative that all too often ignores them.

We asked Miller about barbecue’s origins, how African Americans popularized it, and where you can snag some of the best barbecue in the country.

Resy: What prompted you to write a book about the history of Black barbecuing?

Adrian Miller: I was already working on a book about soul food, and it just seemed to me that I needed to write about barbecue because so many soul food joints have a barbecue option on the menu. And it was part of my family tradition as African Americans and so many Black-owned restaurants have soul food side dishes, so I just started looking deeply at barbecuing.

As I learned more, I was just struck at how so many television shows, newspapers, and magazine articles never referenced Black people. By watching television, you wouldn’t even know that Black people barbecued, and I knew that was off.

Once I noticed that, I said it was a problem. Barbecue is hugely popular now and people are making a profit from it, and so I wanted African Americans to share in that barbecue prosperity.

Why do you think traditional media erases African Americans from barbecue coverage?

The people who make decisions about what barbecue stories get told tend to be white and they have non-diverse networks of people, or they don’t value diversity. So, when they’re trying to figure out whom to highlight, they either talk about other white people or they consume media that talks about other white people. And they put no effort in getting African American stories — even though they’re not hard to get.

Did African Americans invent barbecuing?

OK, so this is a matter of contention. My feeling is no, and that was one of the biggest surprises of my research. Looking at the available evidence, it points to a Native American foundation and then it gets fused with European and African meat cooking and seasoning techniques. So, I think it’s Native American in origin. Some think it’s African in origin, but I can’t find strong evidence of that.

How old is barbecuing?

I don’t know how old barbecuing is, but in the 1490s, Christopher Columbus and his crew first observed it. But that kind of cooking has probably been around for a long time. Some people say it was in Hispaniola. One thing I saw points to Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, where Columbus went on his second voyage. The tribe that people talk about usually gets traced to the Dominican Republic — people tell me it was the Taino.

How did barbecuing get to the United States?

The argument is that it was “discovered” in the Caribbean and then Europeans brought their animals and introduced that type of cooking in the American South, but that supposes the indigenous people didn’t already have their own traditions. We don’t get any accounts of cooking large, whole animals over a trench filled with hardwood coals until Europeans and enslaved Africans got involved with this type of cooking.

What can you say about the importance of African Americans’ contributions to barbecuing?

African Americans perfected this new brand of cooking that developed in the American South because African Americans were barbecue’s go-to cooks. Their skills with smoking and seasoning developed what we call barbecue today.

When did we start barbecuing?

During slavery. That’s one of the reasons why barbecuing exists and became popular, because it was labor intensive. The area had to be cleaned, the wood had to be chopped and it had to be burned. Somebody had to maintain the fire, fill the trench with coals, kill animals, and process them. Somebody had to flip them so they wouldn’t burn, and somebody needed the sauce to keep the meat moist and then somebody had to serve all of that food. And then when the white people were done, somebody had to entertain them with cakewalks, singing plantation melodies, singing spirituals, dancing, you name it. So for most white southerners, a barbecue was a Black experience from beginning to end. And because it’s labor intensive, if you want somebody to do the work and you don’t want to pay them, you made Black people do it.

How often did people barbecue during slavery?

Barbecues went on all the time. The biggest ones were after the main planting work was done and then after the harvest. Some were on the Fourth of July. Any time a politician was running for office and wanted to have a rally, there was barbecue. It was done for churches, camp meetings, and multiple-day retreats to convert enslaved people to Christianity. They had huge feasts during the break.

How did African Americans enrich a barbecue culture that has since gone mainstream?

We were the principal cooks, so barbecuing was associated with slavery, and so where slavery spread, barbecues soon followed, because enslaved people made barbecue happen. After Emancipation, Blacks were recruited to communities to do a barbecue and in many situations, they would stay there. Mostly they were short appearances, but some decided to stay. Those who stayed often kickstarted that region’s barbecue scene. Like Columbus B. Hill. He came from west Tennessee to Denver in the 1870s and he was doing barbecues for up to 25,000 people in Colorado.

Was barbecuing a business or a hobby for them?

They were barbecue’s most effective ambassadors. Think of it as a gig economy — getting paid as freelancers. Some made a lot of money and others decided to open more permanent locations.

Today, what are some of your recommendations for Black-owned, standout barbecue spots across the U.S.?

Grady’s Barbecue in Dudley, N.C.

It’s one of the few remaining African American-owned barbecue joints in North Carolina, and here you’ll get sublime barbecue with soulful side dishes. I recommend the chopped, vinegar-spiked pork shoulder with butter beans, coleslaw, and hush puppies.

Burns Original BBQ in Houston

The late Anthony Bourdain hit this spot as he ate his way through H-Town for an episode of his wildly popular television show. I recommend the pork spareribs, chicken, and hot link sausages.

Gates BBQ in Kansas City, Mo.

This longtime barbecue restaurant exemplifies “Kansas City” as a “melting pit” of eclectic barbecued meats. The ribs and brisket are the move here. Get the mutton if it’s available.

Bludso’s BBQ in Los Angeles

I never expected to find next-level, Texas-style barbecue in Los Angeles. The brisket is superlative, and you should wash down your meal with some refreshing agua de Jamaica, a hibiscus drink with roots in West Africa.

Rodney Scott’s Whole Hog BBQ in Charleston, S.C.

There aren’t many places serving whole hog barbecue, and Rodney Scott excels at it. Get the whole hog barbecue sandwich: white bread topped with chopped pork with crispy bits of pork skin mixed in, all topped with a spicy vinegar sauce.

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Lenore T. Adkins is a freelance food writer based in Washington, D.C., who has been eating her way through the District for seven years. Her work has appeared in Food & Wine Magazine, the Washington Post, the James Beard Foundation website, Eater DC and elsewhere. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter. Follow Resy, too.

Resy Presents

The Community Series

-

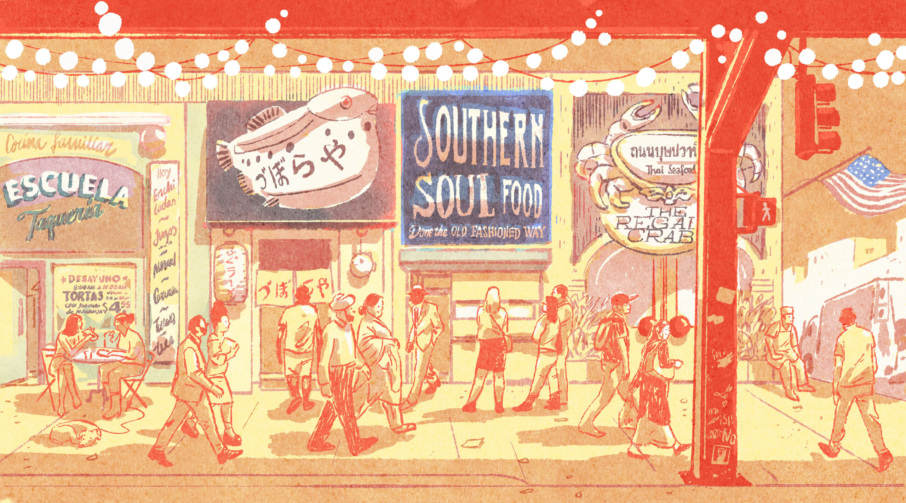

Because This Is What Community Looks Like

Welcome to Resy’s Community Series, a celebration of the people and places that make our communities special, told through their own voices and perspectives. -

‘We Are Still Here’: On Standing Up for San Francisco’s Black Community

Chef and San Francisco native Tiffany Carter on fighting to preserve African American culture, and her guide to eating your way through her hometown. -

Hmong Food Isn’t a Cuisine. It’s a Philosophy.

Hmong American chef Yia Vang on his long journey to open one of the first Hmong restaurants not just in Minnesota, but in the whole country. -

A Chef’s Eating Guide to the Twin Cities’ Hmong Village

Follow Hmong American chef Yia Vang on a tour of his favorite stalls at Hmong Village, a sprawling indoor market and the epicenter of Hmong cultural life in the Twin Cities. -

On the Resilience of Long Beach’s Cambodian American Community

Cambodian American food content creator James Tir on a community that’s struggled through genocide, racism, and poverty, but is also so resilient despite it all. -

New York Has Incredible Mexican Food. Here’s Where to Find It.

Taco Literacy professor Steven Alvarez gives us his personal tour of some of the city’s best Mexican restaurants, and the stories behind the people who run them.