On the Resilience of Long Beach’s Cambodian American Community

James Tir is a Cambodian American food content creator and Long Beach, Calif. native who grew up in Long Beach’s Cambodia Town. His words follow.

James Tir is a Cambodian American food content creator and Long Beach, Calif. native who grew up in Long Beach’s Cambodia Town. His words follow.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that meeting new people — breaking bread with others — is one of the most enriching things you can do. People open up to you when you’re eating with them — it’s when they’re the most raw.

I should know: For the past five years, I’ve documented every restaurant meal I’ve had in my hometown of Long Beach, Calif. on Instagram, and what keeps me going isn’t the food. It’s the people I’ve met along the way — the people who make up the incredible communities that we have in Long Beach. I’ve learned so much from all those meals, and what it means to be part of a community that’s always found expression through food.

The Cambodian American community I grew up in is at a point where we are just now really opening up, showing people how proud we are, and how much we feel at home here in Long Beach’s Cambodia Town. It’s a community that, for so long, has been invisible. A community that has struggled through genocide, racism, and poverty, but is also so incredibly resilient despite it all.

This is my story of growing up in Cambodia Town, which stretches about a mile from Atlantic to Junipero Avenues along Anaheim Street in East Long Beach. Lining the sidewalks are palm trees and jacarandas, shading the Khmer-owned businesses, some of which look almost like any other store or restaurant you might find in Southern California, some with Spanish Mission-style tiling, some in ubiquitous strip mall-style structures. Some businesses resemble something vaguely Asian, although it’s clear they don’t look anything like the temples you’d find in Angkor Wat.

I hope that by telling my story, I can give you a tiny glimpse into what our community is like — what we treasure and what we’ve overcome. How food and restaurants became a way for us to make Long Beach our new home. And who knows? Maybe it’ll convince you to come and break bread with us, too.

One thing that’s really kept the Cambodian American community together here is food, and restaurants. Food has always played a central part in the history of the Cambodian American diaspora.

A lot of the earliest Cambodia Town restaurants catered to the community by serving authentic Cambodian dishes. Sometimes, they might also serve Chinese and Thai dishes to make themselves more palatable to the general public. But mostly, they were for the community itself.

One of those restaurants is my aunt’s restaurant, Hak Heang, and it’s still here today. It’s kind of like a nexus for the Cambodian community because it’s massive; it seats hundreds of people. There’s always live music going on. Any major celebration, from weddings to graduations, is celebrated there. My aunt no longer runs it, but our extended family members still do.

Thanks to Hak Heang, my aunt was able to sponsor my mom, and so many of my other family members. Both of my parents worked at the restaurant at one point; so did I, as a busboy in middle school and high school. It was grueling work, but it made me really appreciate all the people who work there. I’m grateful I had that experience.

The food served at Hak Heang tastes like home to me. As a kid, I loved slurping down bowls of rice porridge, similar to Chinese congee, but made with chicken broth and topped with surplus shredded chicken and green onions and garlic. I devoured bowls of Phnom Penh noodles, sipping broth in between each bite. I remember feasting on yao hon, Cambodian hot pot. Every family has its own recipe for it; in my family, we like to use butter to make it super savory. I also loved eating slab moan boak, stuffed chicken legs where the bone is removed from the thigh and stuffed with lemongrass and ground meat.

My own story, though, really begins with my parents.

Both of them are Cambodian refugees who fled the Khmer Rouge and came to Long Beach as teenagers in the 1980s, like so many others who settled in Long Beach from the 1970s to 1990s. They met at Woodrow Wilson High, fell in love, briefly moved to San Jose, Calif. where I was born, but then they came back to Cambodia Town where they raised me.

It’s estimated that nearly 160,000 Cambodian refugees made their way to America in those years, and many of them settled here in Long Beach, where we now have the largest concentration of Cambodians outside of Cambodia.

It wasn’t easy for my parents when they first moved here. There was a lot of anti-Asian sentiment due to the Vietnam War, so they faced a lot of racism. Especially my dad. When he went to Wilson, he’d get Super Glued to his seat, or thrown off the bus if he didn’t know how to speak English properly.

I also remember doughnuts. So many doughnuts. When my parents moved back to Cambodia Town, they ran a doughnut shop called the Daily Donut, in Westminster. Daily Donut doesn’t exist anymore, and my parents only ran it for a few years, but I remember walking behind the counter and poking my fingers into the doughnuts as a toddler, and getting yelled at for doing that.

There’s a long history of Cambodians running and owning independent donut shops throughout California, especially in Southern California, mostly because of the “Donut King,” Ted Ngoy. I have no idea if he was somehow connected to Daily Donut, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he was.

The other thing I remember most about Daily Donut is how it was such a meeting place for everyone. The regulars were all different races and backgrounds and they felt like they belonged there. That was so special; it really echoed that idea of breaking bread with others, and how food really brings us all together.

Find James Tir’s personal recommendations on where to eat Cambodian food in Long Beach here.

The doughnut shops and the Cambodia Town restaurants were ways for our community to make Long Beach our home, but Cambodia Town itself was sometimes like a double-edged sword.

For me, and for my parents, it was always comforting to be surrounded by a community of people who understood us — who knew where we were coming from. But it could also be stifling.

I think that’s why my parents left briefly to try to make things work out in San Jose, Calif., where I was born, but then they eventually came back and opened the doughnut shop. It’s hard to leave.

Growing up in Cambodia Town was hard for me, too. It wasn’t necessarily a very safe neighborhood. There were warring gangs and, with the influx in refugees at the time, there was discrimination. We weren’t particularly fondly looked at. It was a bad environment, and somehow, I made it out of there. Nowadays, my family and I live in North Long Beach, but I still feel connected to Cambodia Town.

I think that, for a long time, our community was a bit insular, or we just weren’t really known. It was kind of like we were invisible. Even these days, I think most people don’t even know who Cambodians are as an ethnic group.

The majority of our community still lives in poverty. I got really lucky because I had the support of my parents; my mom stayed home to take care of me. But a lot of kids in our community drop out of high school and they get into gangs. Gambling addiction is a huge problem in our community. It’s cyclical.

I know some people are probably surprised by this. This is the complete opposite of the model minority myth that everyone thinks applies to Asian Americans as a whole. It’s complicated.

But if there’s one thing I do want people to know about our community it’s that we are very resilient. There’s this shared trauma among us because of what happened with the Khmer Rouge, with the mass genocide. A lot of people lost family members and friends; my dad lost his dad in that whole thing. But we’re all growing from it, growing from that trauma.

For me, and for my parents, it was always comforting to be surrounded by a community of people who understood us — who knew where we were coming from.

That’s probably one of the main reasons why we haven’t been able to really expand as much outside of our community, but there are members who are pushing us as a community to get out and do more things. When you go through something extremely horrible and you’ve come out of it, it really gives you some resolve, and there’s a lot of it here.

There are many of us who say, “I’m going to do something with this. I’m going to take what I’ve learned and hopefully make the next generation better.”

You see that in how Cambodia Town got established as a business improvement district back in the ’90s, to be classified as its own neighborhood. Every year, we hold a huge Cambodian New Year’s fair at El Dorado Park, where the entire community comes together and everyone is invited. We have a parade. And now we have a lot of second-generation Cambodian Americans trying to make a difference, too.

We’re opening up ourselves more now, and especially through our food over the past six or seven years.

Now there are all these new spots from Cambodian Americans from my generation, like Thyda and Chet Sieng, who are putting a Khmer spin on Nashville hot chicken with Firebird Hot Chicken, or Vannak and Manika Tan over at A&J Seafood Shack. Or chef Tarak Ouk, also known as Chef T; it was a big deal that he became the executive chef of Gladstone’s, this established seafood restaurant on the pier; it was a position of clout.

There’s this huge sense of pride that I have seeing our food community in Long Beach grow and become more diverse. As a city, we’re growing, but as a community, we’re growing because we’re more a part of the city now, too.

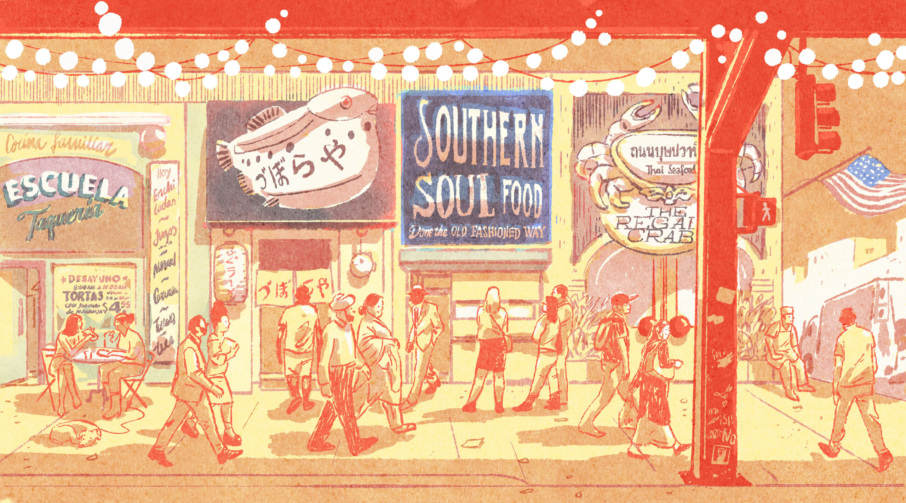

Long Beach is this really special place where you have all these different people with different economic situations, religions, and backgrounds, and we all go to the same restaurants — we all sit at the same table.

Outside of Long Beach, you’d be hard pressed to find authentic Cambodian food like we have here — it’s hard to experience anywhere else. And for our community to survive through everything — the racism, the riots, the pandemic, the genocide — to open up businesses and raise our families and make it through all of these challenges, it’s impressive.

My community has taught me to be proud of who you are, to barrel forward and follow through with what you want to do.

For me, what I want to do is continue seeking out human connections. Breaking bread with people, whether it’s over a slice of pizza or a bowl of Phnom Penh noodles makes life more diverse and interesting, and it’ll eventually bring you to what you want to do. I think it’ll help all of us find our way.

James Tir is a Cambodian American food content creator and Long Beach, Calif. native who’s been documenting the incredible restaurant scene in his hometown for the last five years. You can follow him on Instagram.

Find Tir’s personal recommendations on where to eat Cambodian food in Long Beach here.

Resy Presents

The Community Series

-

Because This Is What Community Looks Like

Welcome to Resy’s Community Series, a celebration of the people and places that make our communities special, told through their own voices and perspectives. -

A Local’s Guide to Eating Your Way Through Long Beach’s Incredible Cambodian Restaurants

Follow Cambodian American food content creator James Tir on a tour of his hometown favorites. -

‘We Are Still Here’: On Standing Up for San Francisco’s Black Community

Chef and San Francisco native Tiffany Carter on fighting to preserve African American culture, and her guide to eating your way through her hometown. -

Hmong Food Isn’t a Cuisine. It’s a Philosophy.

Hmong American chef Yia Vang on his long journey to open one of the first Hmong restaurants not just in Minnesota, but in the whole country. -

On American Barbecue and the Black Community That Built It

Food historian Adrian Miller doesn’t remember how old he was when he started craving his mother’s barbecued pork spareribs. But he knows it was love at first bite. -

New York Has Incredible Mexican Food. Here’s Where to Find It.

Taco Literacy professor Steven Alvarez gives us his personal tour of some of the city’s best Mexican restaurants, and the stories behind the people who run them.