Hmong Food Isn’t a Cuisine. It’s a Philosophy.

Hmong American chef Yia Vang (Union Hmong Kitchen) is opening his latest restaurant, Vinai, in the Twin Cities later this year. His words follow.

“What are you?”

Growing up in a small, mostly white community in Port Edwards, Wis., kids would come up to me and ask that question. Every day, the same question.

“What are you?”

I’m Hmong. I’m American. I’m the son of immigrants and I’m about to open one of the first Hmong restaurants not just in Minnesota, but in the whole country.

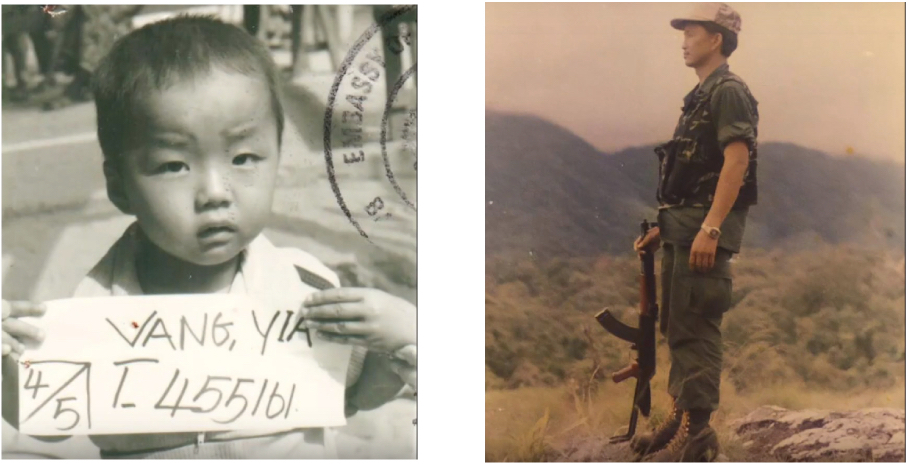

I was born in the Ban Vinai refugee camp in Thailand in 1984.

My family were simple farming people living in Laos when the Vietnam War showed up on their doorstep.

The Hmong have always been stuck in the middle of conflicts across Southeast Asia. The Vietnam War wasn’t any different, except that the CIA recruited Hmong people to fight for them on the ground with the promise of citizenship and America. That didn’t exactly happen. But it’s why my dad and his brothers joined the fight when they were teenagers. It’s why, after the Hmong people were killed in a genocide for helping the U.S. government, they fled to refugee camps. It’s why I was born in one.

Hmong people, we’re like a buoy out in the ocean, and history is the wave that’s pushing us along. The wave comes and goes and the Hmong people either take the hit or they change and adapt to whatever history puts upon them. My family, we adapted.

After living in the Ban Vinai camp for a decade, my parents moved me and my siblings to the Twin Cities in 1988, and eventually, to Wisconsin. I was four years old, and as I started kindergarten, I realized that America was a lot different from the refugee camp I had grown up in.

A lot of us Hmong kids who grew up in smaller white communities, we just kept to ourselves. We didn’t have a place where we could just be who we were. We could only do that when we were around each other, or around family.

Growing up poor, growing up as an immigrant kid, the only way we could literally and tangibly show love to our people was through feeding them. Mom and dad want to show you how much they love you? They don’t buy you horses and ponies; they feed you. That’s what they give.

We would have squash, Hmong mustard greens, string beans, sugar snap peas, all grown from the garden that my parents kept. We would go to farms on a Saturday morning at 6 o’clock, get there, and say, “That’s the pig we want. That’s the cow we want.” All of us kids, we’d gather around, and we would butcher it and break it down together, on the spot. That was my childhood. I thought that was a normal Saturday for most kids. We didn’t do swim lessons, T-ball, or basketball camps.

Still, I felt different.

In elementary school, this kid who I thought was my friend put his hand on my face and said, “I’m going to call you flat face.” For the whole year, that was my nickname. Kids love to point out differences. Nobody ever wants to be the weird-looking kid. I just wanted to be normal.

That’s why I rejected Hmong food growing up. I wanted to eat hamburgers. I wanted to eat freaking grilled cheese sandwiches. Instead, I was the kid who brought the stinky lunch to school.

Even when I started cooking, I wanted to hide from Hmong food. When we first opened our pop-up, we called it Union Kitchen. We added the word “Hmong” later because I didn’t think people would care at first. But they did. We were getting some press and I was feeling pretty good about myself.

That all changed when my dad had a work accident, cracked his skull, and was in the hospital soon after. I remember sitting in the ICU. It was so dark, and there was my dad, my hero, with a bandage over his head. I held his hand and asked him, “Do you remember who I am?” He opened his eyes slowly, looked at me, and he mumbled, “I think you’re my son.”

This was four years ago. I drove home in silence and thought to myself, “If that man dies on that bed, no one is going to know his story.” This sounds so stupid, but I still remember exactly which freeway I was on, the I-94, and in my head, I kept thinking, “From now on, it’s going to change.”

This isn’t about Yia and his food, or Yia winning some James Beard award, or Yia and his restaurant. I realized that all of this press doesn’t mean shit when my dad was on that bed. My father survived a war; he shouldn’t have made it out alive. And just because he slipped on a stupid ladder at work, now he could die?

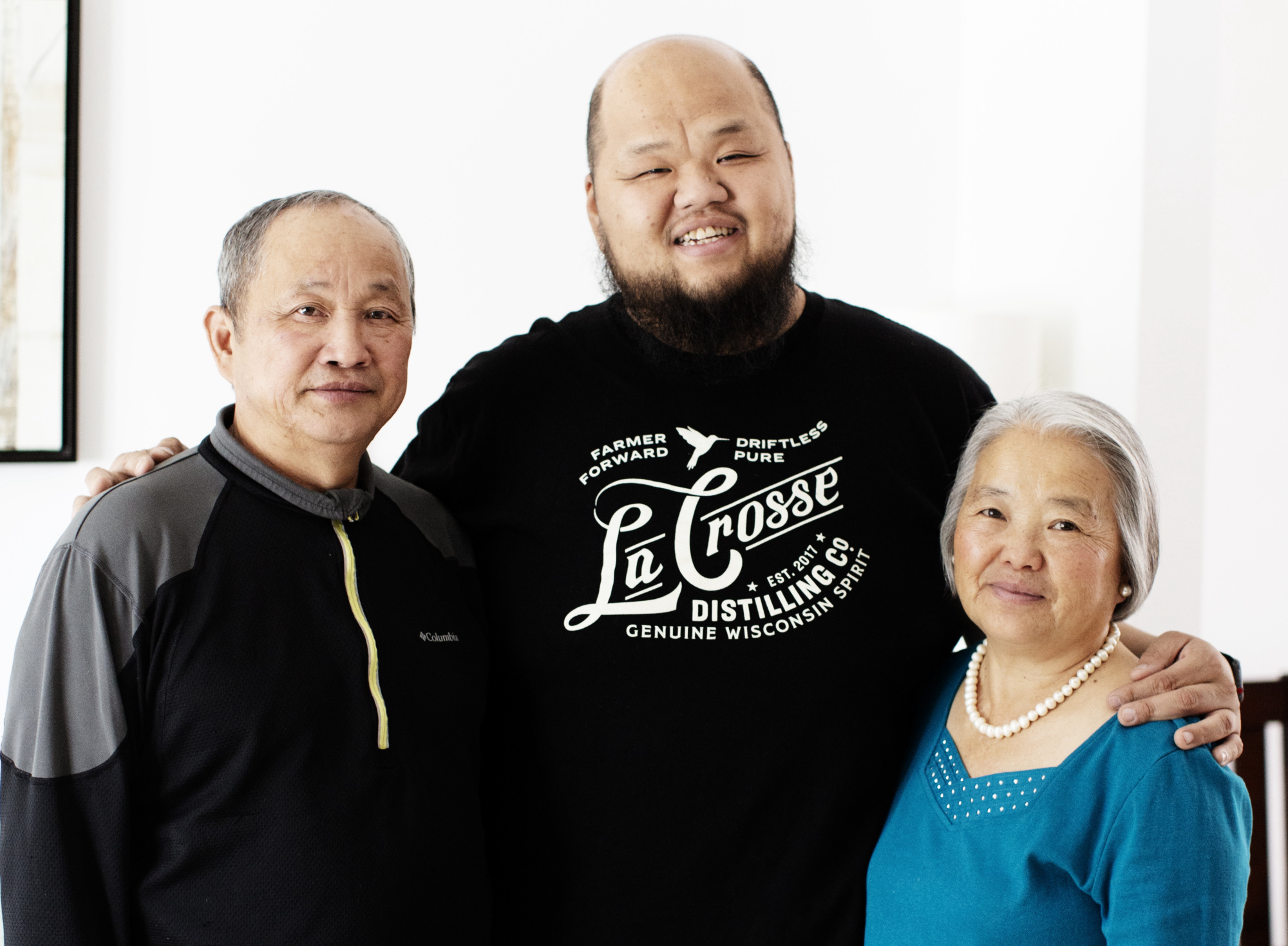

When they came to this country, my parents didn’t have anything.

All they could pass down to us was their legacy. So, I thought, what am I going to do with that? I do it through food. And that’s how Vinai, our upcoming brick-and-mortar, named after the Thai refugee camp I grew up in, came to be.

Every dish at Vinai has a narrative, and through them, people get to hear our story. There’s Mama Vang’s hot sauce, which my mom makes for us. Depending on the season, she’ll make 70 to 100 gallons of it. My dad’s out in the garden right now, growing plants and produce and getting ready for the restaurant. There’s the Hmong sausage he taught me how to make. The way we do sticky rice, I learned that from my mom, standing by her and watching her hands. She taught me how to ferment mustard greens, but I still screw it up, I don’t know how. She often likes to remind me when it’s messed up.

I also can’t deny the fact that as a Hmong American kid, I grew up in America. I’m affected by it. Like the chicken sandwich that my mom would make when she’d bring back damaged, botched chickens from the Tyson factory where she worked. Those sandwiches made me feel like a normal kid, because they were something that my white friends would eat at home. So, when I put a fried chicken sandwich on the menu at Union Hmong Kitchen, I tell people that’s as much part of my food story as anything else.

Still, people will say, “You’re a Hmong kid, you should only be making Hmong food!” And it’s really damning to my soul to hear that. That you’re only a real person if you make Hmong food a certain kind of way.

But Hmong food isn’t a certain type of cuisine. It’s not about a certain type of topping or produce. Hmong food is a philosophy. It’s a way of thinking about food that’s all-encompassing. If you want to know our culture and our people, just look at our food. Because our food is intricately woven into our cultural DNA. It tells the story of who we are.

Us Hmong, don’t have a home of our own. We don’t have a country of our own. History is always determining what our next step is.

And again, just like that buoy in the middle of the ocean getting pushed around, because of the sacrifices of my grandparents and my parents, because my dad fought in the war to get us to America, we get to be in control of our destiny.

To me, being Hmong is about sacrifice. It’s about you laying down everything you have so that the next generation gets to build on that. A whole generation of Hmong men and women died during the Vietnam War and its aftermath so that the next generation could tell their story. My family fought this war believing that one day, we could get to build and be a part of America. I’ll be honest, it’s not perfect, but I believe in that dream.

I ask myself, what am I doing to echo their legacy? Last May was AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) Heritage Month, and I really thought about the word “heritage.” What is heritage? It’s an offshoot of the word inheritance, something to pass down.

I ran so far away from who I was, I literally ran in a circle back to it. Now, I know what I want to do, I know who I am, and I know what my culture is. In everything I do, I ask myself, “Does this bring honor or recognition to mom and dad’s story?”

I want to cook food that I know. Food that I understand, food that makes sense to me, food that rejuvenates me and makes me come alive. We’re hoping that Vinai becomes a beacon and a place where young Hmong kids can come and be themselves. Like Hmong Village — Hmong people come from all over the U.S. to this Saint Paul marketplace because it’s such an institution and one of the pillars of the Hmong community.

And for the future, Vinai gets to set the tone, so the next wave of Hmong chefs can say, “Hey, we want to build on that.” Hopefully, they can tell their own story, and find their own path. Part of being Hmong is finding your own path. And that path somehow always ties back the community as a whole.

At the end of the day, I still feel like that 10-year-old Hmong kid who’s like “Did I do this right? Are you proud of me, Dad?”

A trained chef, Yia Vang worked at many top restaurants in the Twin Cities before starting Union Hmong Kitchen, and has been featured in the New York Times, National Geographic, and Bon Appetit, as well as showcased on PBS, CNN, and more.

His new restaurant concept, Vinai, opening in 2021, is named after the refugee camp in Thailand where he was born. Yia believes that every dish has a narrative, and his mission for Vinai is to create a home for Hmong food that celebrates his parents’ legacy and tells his family’s story through food. Follow him on Instagram.

Find Vang’s personal recommendations on where to eat at Hmong Village, an iconic St. Paul marketplace that’s intrinsic to the Hmong American community, here.

Resy Presents

The Community Series

-

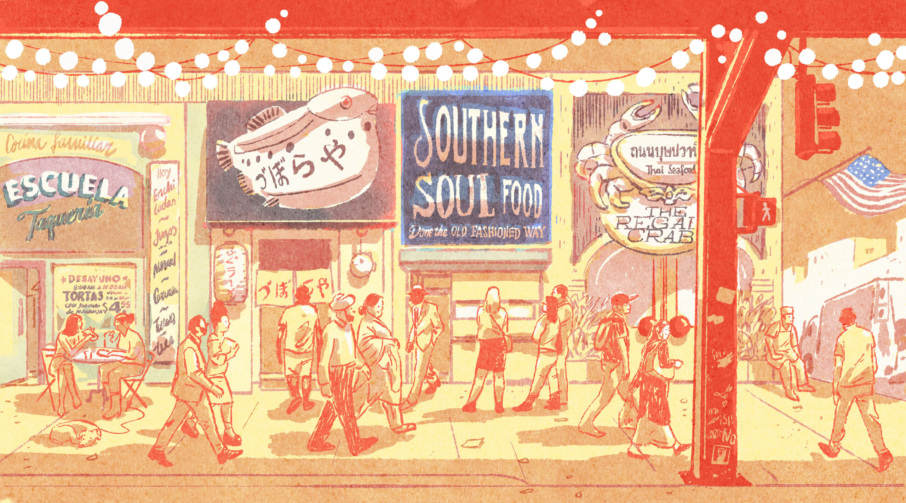

Because This Is What Community Looks Like

Welcome to Resy’s Community Series, a celebration of the people and places that make our communities special, told through their own voices and perspectives. -

‘We Are Still Here’: On Standing Up for San Francisco’s Black Community

Chef and San Francisco native Tiffany Carter on fighting to preserve African American culture, and her guide to eating your way through her hometown. -

On the Resilience of Long Beach’s Cambodian American Community

Cambodian American food content creator James Tir on a community that’s struggled through genocide, racism, and poverty, but is also so resilient despite it all. -

On American Barbecue and the Black Community That Built It

Food historian Adrian Miller doesn’t remember how old he was when he started craving his mother’s barbecued pork spareribs. But he knows it was love at first bite. -

A Chef’s Eating Guide to the Twin Cities’ Hmong Village

Follow Hmong American chef Yia Vang on a tour of his favorite stalls at Hmong Village, a sprawling indoor market and the epicenter of Hmong cultural life in the Twin Cities. -

New York Has Incredible Mexican Food. Here’s Where to Find It.

Taco Literacy professor Steven Alvarez gives us his personal tour of some of the city’s best Mexican restaurants, and the stories behind the people who run them.