At Alta Adams, a Community’s Story Is Told on the Walls

In the open kitchen at Alta Adams, the various threads of California cooking, Southern flavors, and chef Keith Corbin’s West African heritage meld together to produce a distinctive cuisine that has earned critical acclaim and devoted diners. The food, though, is just one part of the story. Since opening in 2018, Alta’s approach to hospitality has been to reflect its local community — and the evidence is right there on the walls.

Corbin and chef Daniel Patterson first met while working at the now-closed LocoL in Watts, the historic south L.A. neighborhood where Corbin grew up. In 2018, the duo partnered to open Alta, where they serve their own versions of comfort soul food, like black-eyed pea fritters with spicy herb sauce and blackened salmon in curry broth, in a vibrant space that moonlights as a gallery for primarily local artists.

- How Michael’s Brought the Food and Art Worlds Together, One Painting at a Time

- At the Heart of L.A., Harold & Belle’s Preserves a Legacy and Looks Ahead

- The Resy Guide to the Best Outdoor Dining in Los Angeles

- Wes Avila Wants You to See His Mexican Cooking At Ka’teen As Pure L.A.

- Pizza in Los Angeles Today Is The Best Ever. It’s Also … Complicated.

Terrell Tilford, the founder and chief creative officer of the neighboring art gallery Band of Vices, is responsible for curating most of Alta’s collection. Corbin and Patterson first met Tilford during the restaurant’s build-out and quickly bonded over his work. When it came time to decorate the walls, Tilford’s devotion to showcasing emerging artists of diverse backgrounds made him an obvious fit for the task.

We spent an afternoon at Alta chatting with Tilford, Corbin, Patterson, and Alta’s general manager Asia Stewart-Howell about how the art at Alta mirrors the community and culture of West Adams. From colorful diptychs by the Oakland-based photographer Brittini Sensabaugh to hand-painted murals from neighboring artists, here’s what they had to say about each piece.

Terrell Tilford: I’ve been working on behalf of visual artists since 1999. It started out in New York, and then I brought it back to L.A., where I’m from originally. What’s always been important for me is to be in communities where Black and brown people can have exposure to [the art], because I didn’t grow up with an art gallery in my neighborhood. I like being off the beaten path, although now we’re no longer off the beaten path.

Keith Corbin: We’re on the beaten path.

TT: We built the path. But what was important for Alta is that we’re both of the community and that the artwork reflects the people and the artists of the community at the same time. I was fortunate that both Daniel and Keith had [that notion] on their radar to begin with. I went to the developer first and asked if he knew the cats who were building the restaurant out, and gave him my card. True to form, they called me up, and a couple of days later, we were over here, talking about where pieces could land in the space. Then I laid out about 30 works in the gallery across the street and when Keith and Daniel came over Keith was immediately like, “Boom, that one right there.”

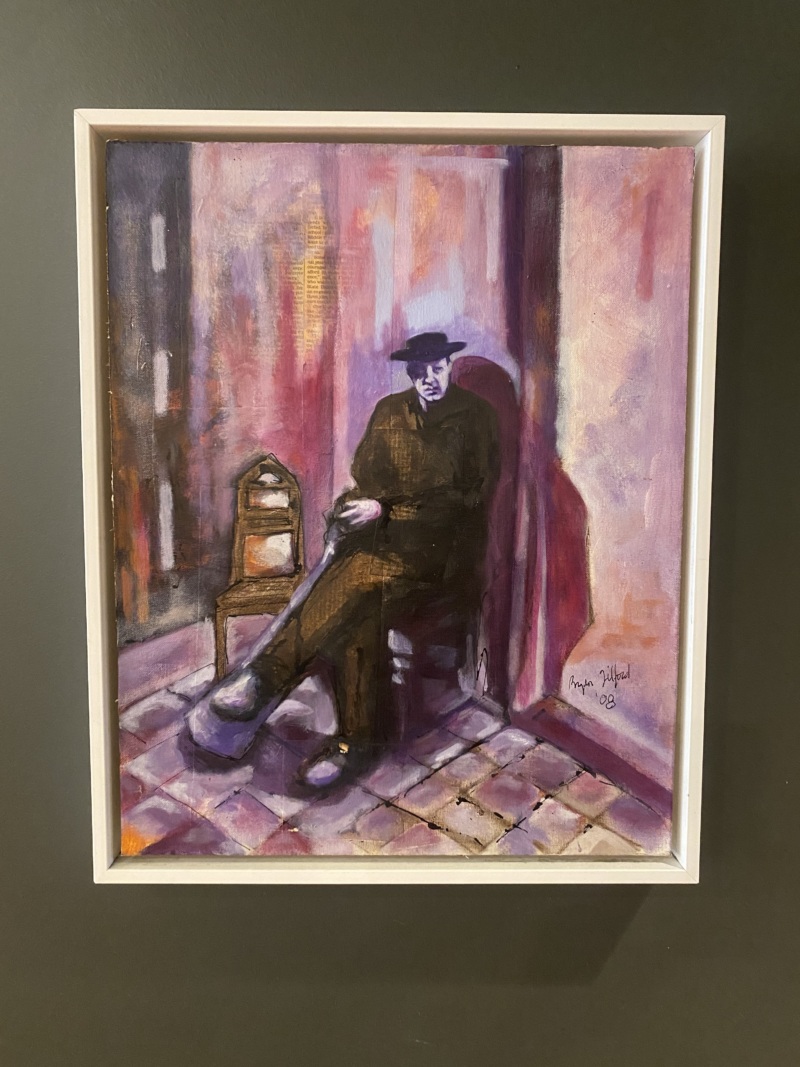

TT: This piece is actually done by my brother, he lived through the Watts riots. And obviously, that’s also a reflection of the Rodney King riots.

KC: Also, that’s where I come from.

TT: Yeah, that was the very first piece that he gravitated toward. I thought it was sort of a bold move for a restaurant to put a piece like that over the bar. But the cool thing about it as well, and I use the saying that my spiritual father uses, which is, “You draw to yourself of yourself so that you may see yourself.” So it’s important that whether it’s abstract figurative photography or sculpture, people see themselves reflected in their own community. Coming into an establishment like this, it’s important for them to see themselves reflected on the walls as well.

TT: My brother also did this piece here called “The Prez,” of Lester Young. In the ‘50s, they called Lester Young the president. He was of the jazz association, and he also played with Miles Davis, Coltrane, and all those sorts of people. Both of these works are acrylic on canvas.

KC: Isn’t he kin to someone? Because someone came in saying that [Lester Young] is his uncle. And then he sent us a photo of the actual photograph of that guy sitting in the corner.

Asia Stewart-Howell: How cool is that? This guy came in to the restaurant and was like, “Oh, that’s my uncle,” and sent this picture, and then we took this one of him and the painting.

TT: That’s Wren Brown! Wow, I didn’t know Wren was Lester’s nephew. Wren and I grew up together. He’s like the unofficial mayor of L.A., he knows everyone’s family history in this area. Right around the corner was what’s now the neighborhood and performing arts center, but it used to be called the Ebony Showcase Theater. Wren is just a few years older than me — he’s an orator and a brilliant actor. That’s it right there, our intention just breeds honesty.

TT: The piece by the front door is called “Altar” and is done by an artist named Jose Ramirez. He’s a Chicano-American artist based here in East L.A., we went to Berkeley together as undergrads. I’ve been working with him since 1999.

Then over here, we have a painting by Edyta Pachowicz. She’s Polish but studied in Atlanta and lives here in L.A. now. It’s called “Breath Fades in Your Absence” and it has such a calming nature to it. It represents a different quality [than the other works in the space], and it goes well with the color palette that they have established here. We work with about 150 artists around the world and 80% are artists of color. When people ask me what I’m looking for in artists, I tell them thought-provoking, fearless, and unapologetic. So I think if you start there, that’s the most honest approach, and then let the artists’ voice speak to their work. About 50% of our artists are based in L.A., but we’ve worked with artists everywhere: Japan, Australia, Cuba, Toronto, Nigeria, Ghana…

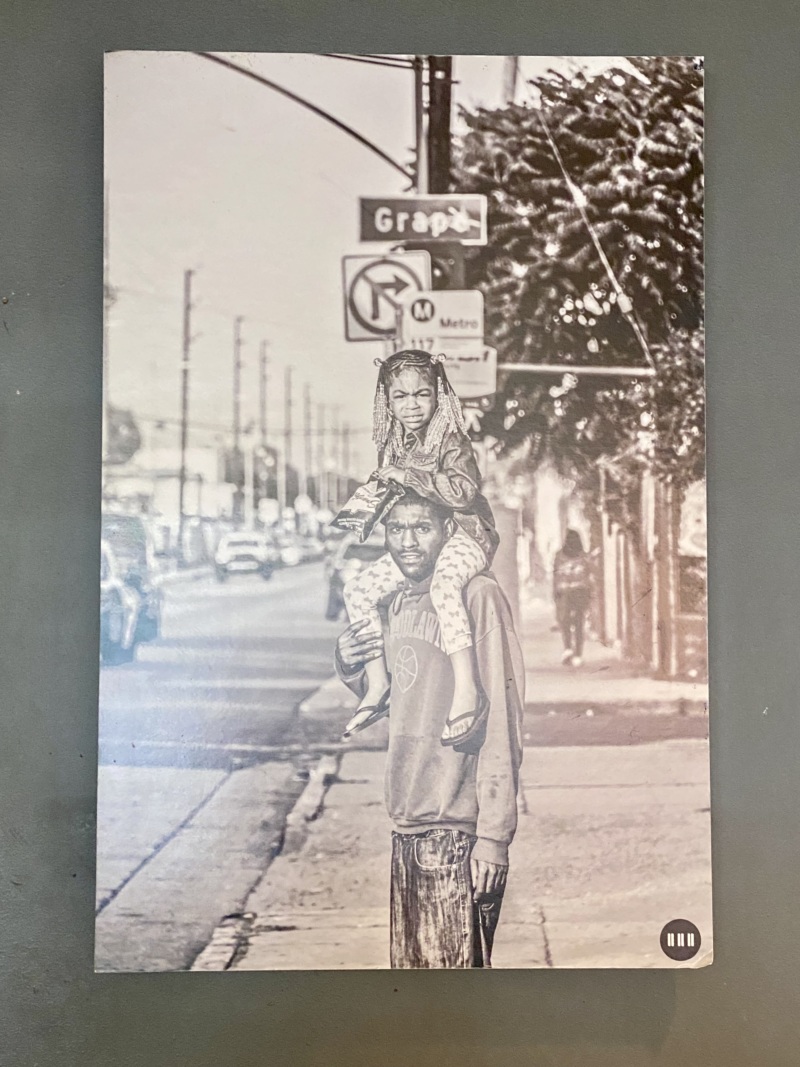

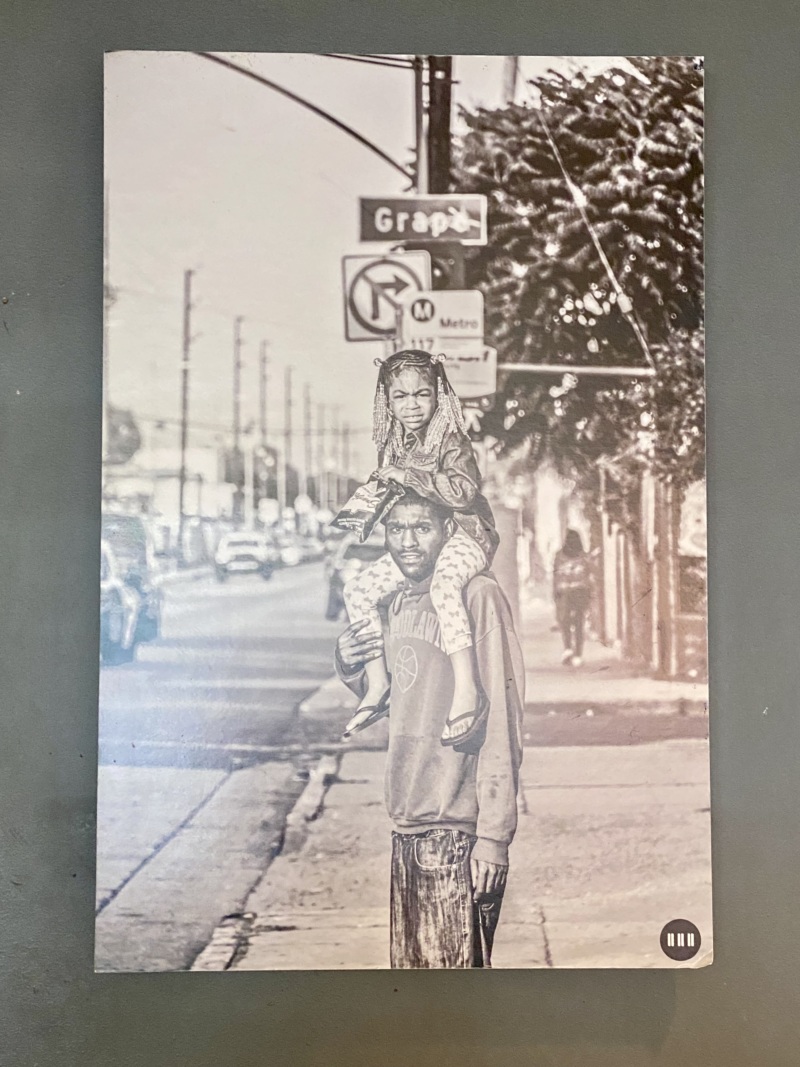

Daniel Patterson: These photographs are by Brittini Sensabaugh, an Oakland-based artist. She does a lot of work in inner cities. They’re from a series called “222 Forgotten Cities” where she documents the lives that don’t show up as much in the mainstream media. Basically, it’s these diptychs showing hair and images from nature, so she’s connecting inner-city communities with natural beauty.

KC: Daniel was actually going to do a project in a San Francisco hotel that fell through, and we had already paid her to do the artwork. So she allowed me the opportunity to go through her photos and I picked all of these. I love this one because all hair at some point goes through that kind of design.

DP: She also did this one. That’s a block away from LocoL, so she went down there and took a picture.

KC: It’s literally where I grew up, on 131st. So to see somebody way up in Oakland that had a picture of a young man that grew up under me with his daughter, right on the very street that I grew up on… I had to have it.

ASH: They come in all the time.

KC: I raised him. We grew up in the same project, and then right across the street is LocoL, where I worked with Daniel and Roy [Choi] and where I got my start.

TT: I just love the juxtaposition of nature and natural. We find and look for the duality in humanity in every which way. I think one thing that’s incredible — and obviously, Keith can speak to this — is when you marry food and culture and people, it just creates commonality and brings people together. That’s why I’m so appreciative that you don’t have TV screens. Having these natural woods in here, and then having printed colorful pillows and things like that, makes people feel good.

KC: Culturally, how we eat, it’s big momma’s table family-style — getting into kids’ business, having conversations, and listening and learning. Or maybe it’s a picnic or family reunion. Atla’s design is really a representation of how I grew up.

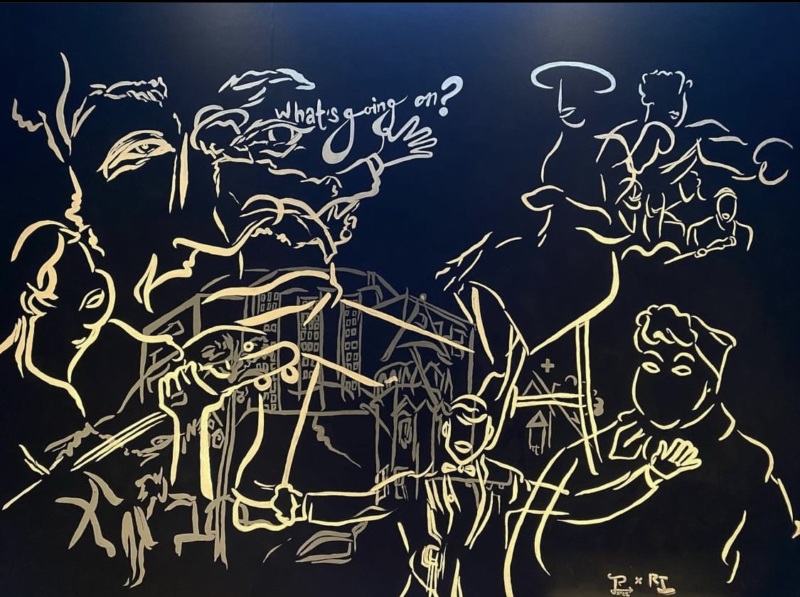

TT: I love these works, it’s a whole West Adams series that she did.

KC: She was painting people in West Adams. She’s also done a lot of the artwork on the buildings, including a pigeon mural between our buildings. She captured me and Gwen [our former chef de cuisine], and also this fella from the mechanic shop, and Ron Finley, the gangsta gardener. She captured all of us in this community and then had an art show with all of our pieces, and then she gave them to us afterward.

KC: This, for me, is about the big conversation about West Adams and gentrification. When we opened, it was our intention to connect to the community that was here. It wasn’t about looking ahead. From the food to the way we hire to the price point, it was about connecting to what already exists. Of course, the community is changing. So this is our opportunity to maintain some history about West Adams. You have people that literally made Sugar Hill, which came prior to West Adams. Black folks like Bojangles and Hattie McDaniels were responsible for it, and then they destroyed our community with the 10 freeway. On the other side, this represents how we all grow, like me in Watts. No matter where I grow, or how high I reach, my roots are always in Watts. We are, in my opinion, the roots of culture, whether it be music, art, food …

TT: I haven’t seen this yet, oh my goodness.

KC: So that’s West Adams, where we are, on one side. On the other, that’s my community, my city — Watts. I just love this. I asked somebody to come up with a piece for this bathroom. Originally we had the streets of West Adams, but since West Adams is represented [in the other bathroom], I wanted to combine it with Watts here, which are together probably the biggest Black communities in L.A. It’s about giving everyone an opportunity. In our community, women are the backbone. So to have a representation of a strong black woman and the power of her hair is everything.

TT: It’s so dynamic, because that whole neighborhood, that whole community, is a crown jewel.

Emily Wilson is a Los Angeles-based food writer from New York. She has contributed to Bon Appétit, Eater, TASTE, The Los Angeles Times, Punch, Atlas Obscura, and more. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram. Follow Resy, too.