The Diner Finds a New Life. A Better, More Complicated One.

At my local diner, a block from my apartment in Manhattan, I can order a two-egg scramble with a pile of greasy bacon, home fries, and toast. Or huevos rancheros with refried beans and crispy tortillas. There is a cheeseburger, linguini with clam sauce, and a chicken quesadilla, not to mention all the bagels, gyros, and panini. The abundance of choice is a signature part of the modern diner experience, and, at least in New York, the far-reaching menus are a living record of the various immigrant communities who have passed through them.

In the late 1800s and through most of the 1900s (and arguably still today), various limitations meant that restaurant work was some of the only work available to immigrants when they first arrived in America. For this reason, the hospitality business has been, and continues to be, a springboard into American life for many immigrant families. Diners in particular proved to be a reliable stepping stone when Greek immigration to America was reaching all-time highs in the 1950s and 1960s. (In the late 1990s, The New York Times reported that Greek immigrants owned about two-thirds of the 800-odd diners in New York.)

For immigrants, the diner was often just a means to an end. But each wave of workers, from Greek to more recent Latin American and Middle Eastern, has left an indelible mark on diner cuisine along the way, giving us the signature mish-mash of comfort foods from elsewhere, adapted to suit local tastes. Over the last century, diners have earned their place as an icon of American culture, shaped by immigrants, here to soothe our collective anxieties. But beyond the symbolism, how does the diner actually stack up in the hierarchy of eating in America?

In the greater context of restaurants, it seems diner food is still not nearly as respected as more chef-driven cooking, of the sort that fuels the dreams of culinary school graduates and lands in the local paper’s fall preview. The efforts of the diner cook, who is often a person of color and not infrequently an immigrant, are easily disregarded as unskilled — and worse, often invisible — labor.

- Barbuto Is Back. And Yes, So Is The Roast Chicken.

- The Most Amazing Things Can Happen After a Meal at Sparks

- The Resy Guide to Vietnamese American Food in New York

- Ten Essential Restaurants Across America, Fall 2021 Edition

- The Family Restaurant That’s Become New York’s Melting Pot for Nearly 50 Years

▪️

Over the last century,

diners have earned their

place as an icon of American

culture. But beyond the

symbolism, how does

the diner actually stack up

in the hierarchy of

eating in America?

▪️

But two restaurants in New York are defying those expectations. Golden Diner and Thai Diner, both in downtown Manhattan, are reframing what a diner can be, by evolving and complicating the definition of diner food and the diner cook — while also reinforcing the democratic and upwardly mobile ideals that make diners an essential, and good, part of the American restaurant tradition.

Samuel Yoo opened Golden Diner in Chinatown in 2019, and the nostalgic design of his restaurant coupled with creative riffs on classic dishes quickly become the prototype for a new American diner (following, maybe, in the footsteps of the short-lived Nickel & Diner in SoHo). Yoo outfitted the dining room with a long counter facing the open kitchen, and swiveling chrome-trimmed stools, referencing the railroad style dining cars from which the earliest diners were born. The menu reflects Yoo’s Korean American heritage while paying homage to the neighborhood, which has been a home to both Jewish and Chinese communities. As such, the Golden Diner burger is topped with a mushroom gochujang sauce, the egg sandwich is bookended by a local bakery’s scallion bread, and the matzoh ball soup is made from scratch.

But in his own way, Yoo is challenging the popular narrative of the diner as a place for cheap food. “I wanted to make a point of creating an inclusive and accessible place that serves food of the highest quality and integrity,” Yoo tells me. The gochujang-sauced burger, for example, is made with beef from Happy Valley Meat Company, a certified B corporation that only sells ethically-raised meat. This kind of provenance is typically the arena of upmarket restaurants, who then charge upmarket prices. Yoo has some experience with this; he previously worked at Momofuku Ko, where “chef’s counter” means something else entirely — and where refrigerators of dry aging steaks and whole ducks serve as the wall art. At Golden Diner, transparency in food origins is similarly valued, even though prices are still relatively low (that cheeseburger costs $17, while the same order is around $15 at my local diner). The restaurant’s website reads like a who’s who of top restaurant suppliers, from the chef-favorite Campo Rosso Farms to the Union Square Greenmarket staple, Bodhitree Farm.

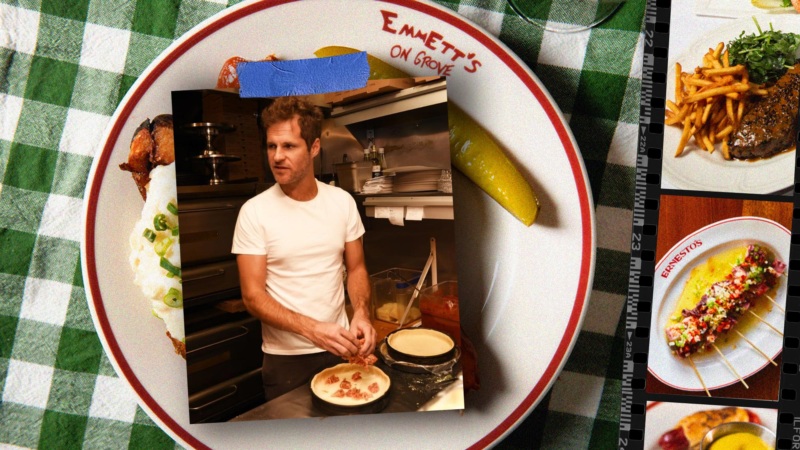

At Thai Diner, chefs Ann Redding and Matt Danzer have similarly upended the traditional role of the diner as a stepping stone to something else. In this case, running a diner is the aspiration after a successful career of cooking. The couple first met while working at Per Se, and both graduated from esteemed culinary programs. Their first restaurant together was Uncle Boons, which opened in 2013 — an interpretation of Redding’s family recipes of Thai dishes, assembled with the experience of two fine dining professionals.

Unfortunately, Uncle Boons and its follow-up counter spot, Uncle Boons Sister, were casualties of the pandemic, closing not too long after Redding and Danzer opened Thai Diner last year. The diner is now their only restaurant in New York.

But as much as Thai Diner is the flagship for two pedigreed chefs, a contrast to so many everyday diners, it still has much in common with the broader tradition. The space has all the visual cues — counter, stools, booths — refreshed with the tropical vibes of bamboo, rattan, and teak. The menu is comfort food updated to suit the tastes of its owners, infused with personality at every turn. The egg sandwich, for example, is wrapped in flaky roti and enlivened with an herby pork sausage. Thai tea babka French toast is as much fusion as it is a declaration of denomination — Thai, Jewish, New Yorker, American. Even the purely Thai dishes on the menu, carried over from Uncle Boons, are a deeply personal style of cooking that fits neatly into the diner genre.

The fact that Yoo, Redding, and Danzer have moved away from the largess of fine dining kitchens and towards short order fare, inverting the cook’s archetype journey — immigrant or not — is a sign of the times, especially as the pandemic wears on, and comfort foods and casual dining continue to proliferate. The diner, not long ago considered an imperiled business model, is a perfect fit. Regardless of the motivations, both Golden Diner and Thai Diner are expanding the definition of what a diner can be. And while the manifestations of this cultural icon continue to evolve, the essential point — good food for everyone — remains the same. Ultimately, as generations of immigrants who have passed through the business already know, the solace found in the pages of a diner menu will always prove its value.

Mahira Rivers is a restaurant critic and writer based in New York. In addition to spending five years as an anonymous inspector for The Michelin Guides, her writing has been published in The New York Times, New York Magazine, Food & Wine, GQ and elsewhere. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram. Follow Resy, too.