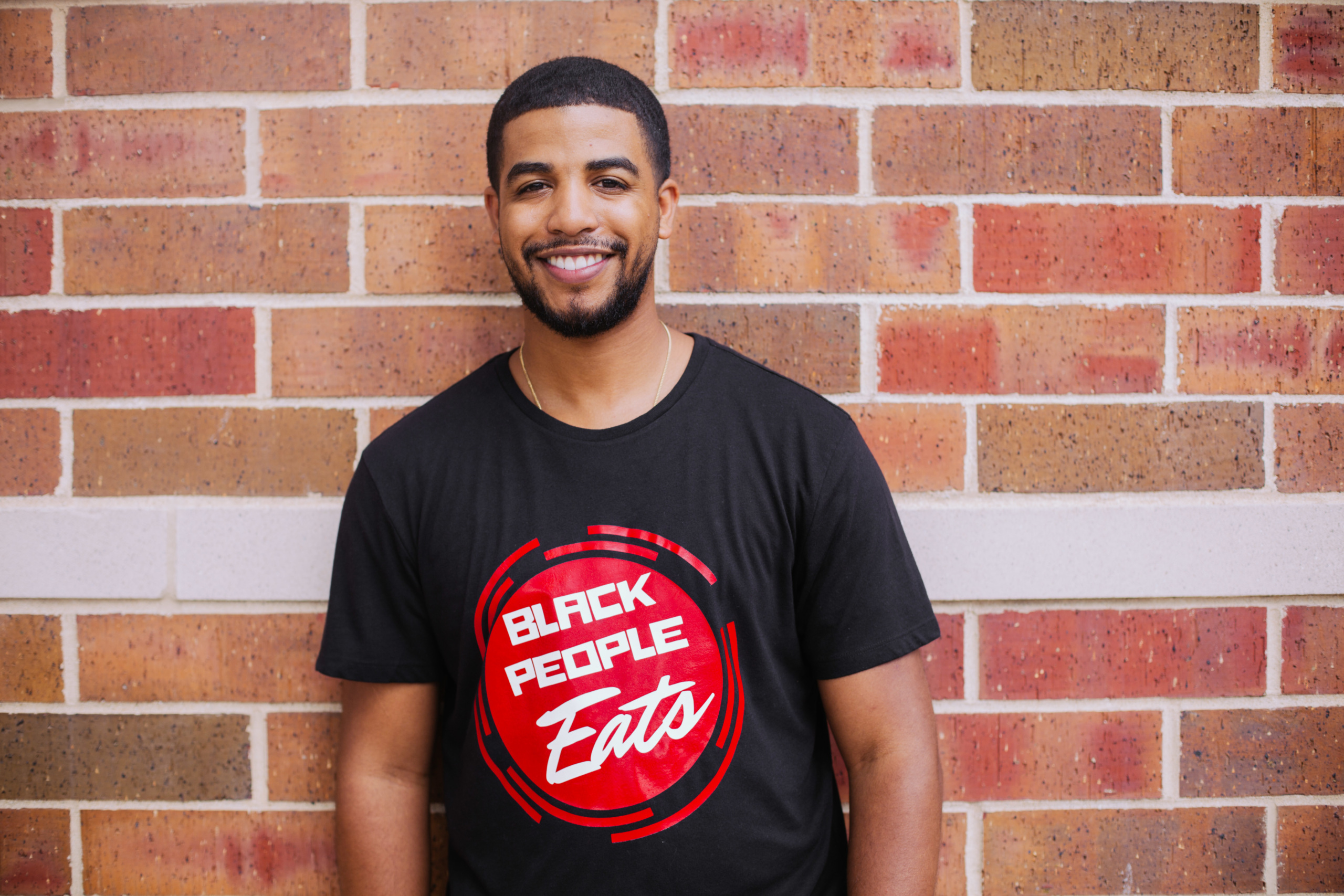

For Black People Eats Founder Jeremy Joyce, Helping Black Restaurants Is Everyone’s Job

It began with a June 1 Instagram post by Chicago food site Black People Eats, checking in on the city’s Black-owned eateries, which were reeling both from coronavirus and weekend looting due to citywide protests following the police killing in Minneapolis of George Floyd. A few hours later, founder Jeremy Joyce set up a crowdfunding site, hoping to raise $20,000 to help a few dozen of the affected restaurants.

The Black-Owned Restaurant Relief Fund blazed past its goal in 24 hours, eclipsing $50,000 by June 6. (The total has since surpassed $70,000.) That milestone figure bears deeper significance, as on that same day Black People Eats’s Instagram topped 50,000 followers, up from 38,600 a week before. Joyce had noted follower spikes before, when he reviewed a particularly buzzy restaurant or was profiled by a local news outlet. Yet these newcomers were inescapably more diverse—overwhelmingly non-Black, and many hailing from outside Chicago.

Joyce, 28 and a Chicago native, created the Black People Eats blog in December 2017, after noticing a lack of coverage of its 150-plus Black-owned eateries by local media in this notoriously segregated city. He has since built a restaurant directory and expanded the site to five other cities, including Baltimore, New Orleans and Washington, D.C. He joined the likes of local food sites like Chicago Black Restaurant Week, Black Food & Beverage and Seasoned & Blessed—many of whom similarly were flooded with new followers in recent days, and saw the Black-owned lists they compiled long ago highlighted on new social platforms urging Chicagoans to patronize Black-owned businesses.

Food writer Angela Burke, the founder of Black F&B, noted that since protests have begun, she has seen a 25% gain in Instagram followers. Chicago food writer and photographer Aaron Oliver, who runs Seasoned & Blessed, told Block Club Chicago that he saw an uptick in click-based referrals to Black-owned restaurants originating on his website—though this largely benefited eateries on the North Side rather than those on the south and west sides of the city, where the majority of Black-owned restaurants are located (and where the impact of COVID and civil unrest is more profound).

Can this wave of enthusiasm and readership translate to a deeper commitment by patrons to support Black-owned Chicago eateries? In a recent interview, Joyce made the point that it will take true effort from those beyond the Black community. This conversation has been condensed and edited.

Tell us when and why you founded Black People Eats. What is the mission?

I started Black People Eats on Dec. 12, 2017, with two goals in mind. One, to showcase where Black restaurants are for everybody. Two, to show you what to eat when you get to a Black restaurant. Out of that, my mission became connecting people and communities to Black-owned restaurants in their cities, and bringing optimism to people’s lives through food.

I started in the restaurant industry at age 16, working at Culver’s until I was 22. [A Midwestern fast-casual chain known for butterburgers, with butter-brushed buns, and frozen custard.] That’s where I really became fascinated and started to understand more about how food can change people, and how great service adds value and gives them joy.

On June 1, following the first wave of civil unrest, you wrote an Instagram post, checking in with Black-owned restaurants to see who was open. Tell me about that and the response it received.

I was like, I know I could call every owner, but that’s a lot of time, so I made a post. Some restaurants commented, “We’re good, we’re OK, we appreciate you. We’re still open.” Some people reached out directly, like Kilwins Chocolates downtown—which is the only Black-owned location in the franchise. They had some issues. Carribean Jerk Palace had a door with some broken glass. A few followers commented that they’d like to help, and asked if I could organize a fundraiser. That’s what sparked the relief fund.

You set up the Black-Owned Restaurant Relief Fund for eateries impacted by looting that same day, right? What was the initial goal? (Applications opened June 10 and over 60 restaurants had applied as of June 16).

Yes, I set up a GoFundMe the same day. The initial goal was $20,000. My team and I debated giving $1,000 to 20 restaurants, but set it up to give $500 each to 40 different businesses, so we could help more. We put it out there, and once we hit $25,000 in 24 hours, I was like, whoa, this is crazy! I literally couldn’t believe it.

We’re keeping the fund open until June 18. Restaurants can submit applications to receive a grant by submitting a business license, filling out a Google form with some questions on how their business was affected by COVID and recent protesting, and how they plan to use money. We’re going to analyze the applications and send people money, no strings attached. We’ll announce the first 40 on Juneteenth. Then we’ll open up another round for 40 more.

Let’s talk about some of the deeper challenges uniquely facing Black restaurant owners in Chicago, resulting largely from the effects of systemic racism and segregation. Some of these include difficulty getting bank loans — less than 47 percent of financing applications filed by African American business owners get approved, according to the U.S. Federal Reserve. But also tighter profit margins and smaller marketing budgets. The pandemic, and resulting economic crisis, and the riots have only exacerbated these issues. What are owners up against?

Honestly, it’s a lot. If me and you try to get a bank loan for our new restaurant and we’re both African American, there’s an issue with getting loans. Even if we can potentially open, we’re disadvantaged. Businesses overall right now are struggling. COVID has caused a lot of job losses …. And if you look at dollars circulating in the community, there is a divider when you come to the South Side, the East Side, areas like Bronzeville on the near Southeast Side.

These owners are facing hard times; there is a food shortage with the companies they order ingredients from. And since some grocery stores shut down, restaurants are the only source of food in some of these communities. Now, let’s say my closest grocery store is five minutes away, but that’s been looted. Another one 15 minutes away is shut down, so I might have to travel an hour. But how do [people of] other races know I’m not going there to loot? It’s an interesting dynamic.

If we don’t get a lot of attention, things can get worse economically. And I have no idea what worse looks like.

That said, all eyes are on Black-owned businesses—and, as you’ve seen with the relief fund—many people want to help. How does Black People Eats hope to leverage this momentum?

We have a lot of attention. Major companies are donating money to businesses. What I believe they need to do is formulate a plan. Getting capital is great, but do you, the owner, have a strategy to execute? Do you have a dedicated marketing or advertising budget? Working with so many Black restaurants, a lot of them don’t have marketing budgets!

From my perspective, and my team has been on me for a while about this, I’m working on an e-book on how restaurants can market themselves on social media. We’re getting ready to unleash a t-shirt and an app. We’re also merging over to events. I was working on a food-tasting festival before all this happened. We’re still going to do something. It just might look different—maybe virtual. And eventually, there will be a Black People Eats in every major city.

You also just rolled out an interactive map.

I’ve had a database of every Black restaurant in every city since I started my [restaurant directory] site last April. At first, I didn’t do an interactive map because I was nervous that somebody would steal the data. With COVID, people kept asking me, “Hey, hey do you have a map?” It took me five minutes to get that up. It comes back to, how close are you to your community? If the community keeps asking for a map, why ignore what they’re asking for?

How can we channel the current enthusiasm into more concrete changes in behavior—for instance, people from all neighborhoods patronizing these businesses regularly, and more equitable media coverage long-term?

Everybody has to play their part. Media and press have to, intentionally, with true care, highlight Black-owned restaurants in all neighborhoods—not just in north Chicago, where most are highlighted. They have to amplify those who have platforms in the Black community. I’m not the only one, of course.

Restaurants have to put themselves out there socially, too. If I haven’t made a post about my business in nine days, you might think I’m not open. We have to make people want to come! Posting content is part of that.

Can you get more people just by posting content though? At the end of the day, some of these neighborhoods don’t see [enough] foot traffic. Yesterday morning, I was in Bronzeville doing an interview, and I can count on both hands the number of people walking by. If I go to Lincoln Park [on the lakefront], there are a lot of people walking around.

Intention is a big part of this, isn’t it? Because restaurants, especially in tight-knit communities, are important community spaces.

That’s why I got started, honestly. It has to be true empathy and true intent. I think about that also when it comes to amplifying these lists because it’s strategic; for us at the end of the day, it’s business. At the same time, my mission is for Black restaurants to be highlighted. You have Black creators getting their information boosted on larger platforms. If our mission is to help, then showcasing that list, even if I don’t get credit for creating it, is still helping Black restaurants. We can’t be the only gatekeepers.

Maggie Hennessy is a Chicago-based restaurant critic and food writer, whose work has appeared in such publications as Eater, Plate, Food52, Taste, Wine Enthusiast and others. She also co-hosts the Overserved podcast. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter. Follow Resy, too.

▪️▪️▪️

Three Chicago spots Jeremy Joyce loves to visit — and what to order when you go

Brown Sugar Bakery | Grand Crossing

“[Owner Stephanie Hart] has this vanilla cream cheese and caramel cake that is to die for. She was one of the first owners I ever talked to. She told me, ‘We don’t have anybody like you. You’re gonna do very well.’ We all need that confirmation when we’re starting out.”

Two Fish Crab Shack | Bronzeville

“The shrimp is my favorite thing to eat. You get it in the seafood boil bag, with corn, potatoes and andouille sausage and one of (owner Yasmin Curtis’s) three seasonings: garlic butter, lemon pepper or Cajun. If you’re crazy like me, you get all three and add jerk. That was until I started to get their deep-fried lobster tail and fried shrimp coated in barbecue sauce. Listen: Go right when they open on Tuesday, Wednesday or Thursday, unless you feel like waiting. That’s when they have a $20.99 shrimp and crab leg special.”

Luella’s Southern Kitchen | Lincoln Square

“They’re not doing brunch again yet, but my favorite thing from there is the brown sugar bourbon French toast. They bake the bread in house and do this homemade brown sugar syrup sprinkled with caramel. I also love the buttermilk fried chicken and waffles and the New Orleans shrimp and grits. [Chef/owner Darnell Reed’s] food is wonderful.”

Discover More