Women of Food National New York

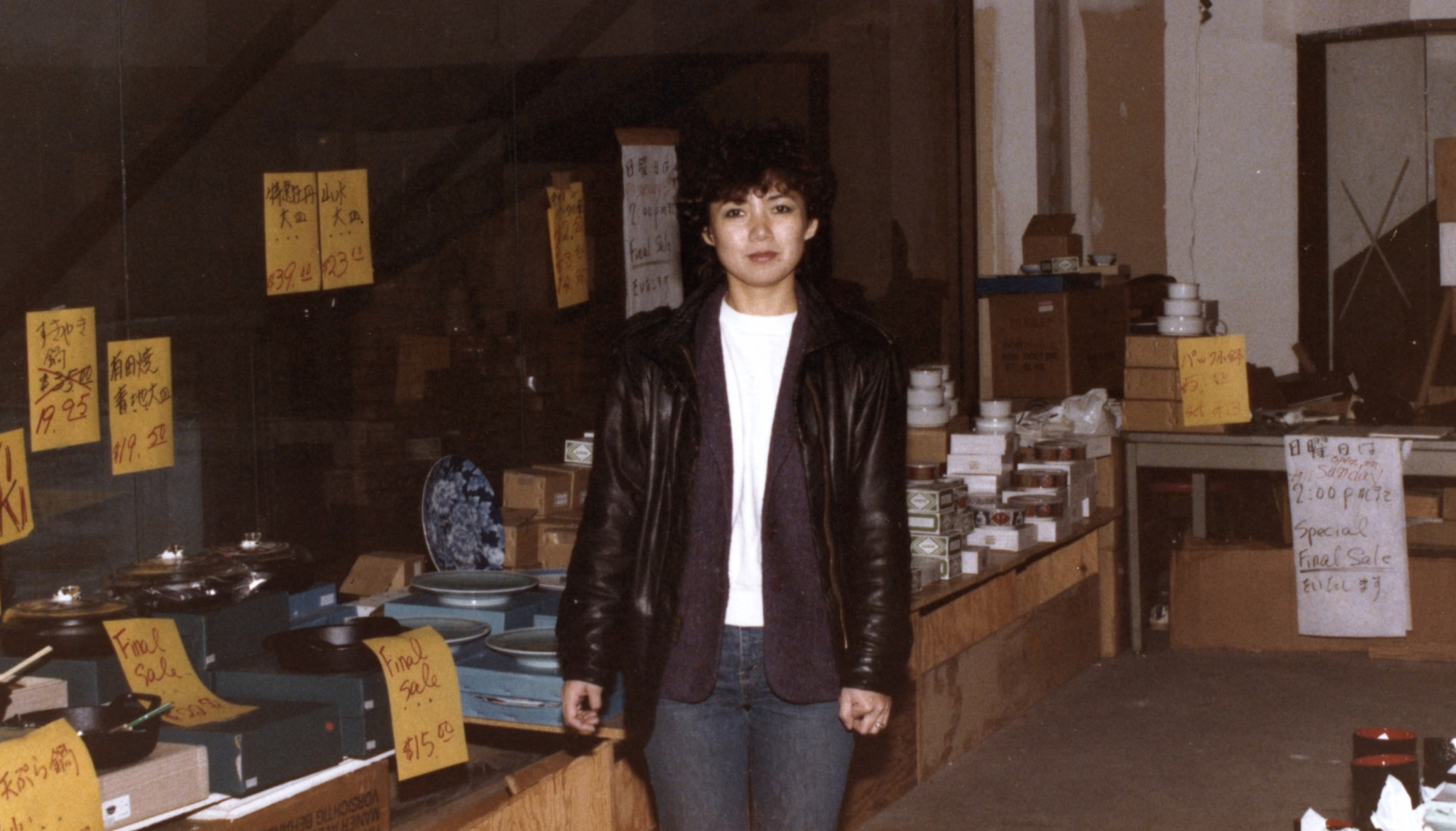

Meet Saori Kawano, the Woman Who Introduced America’s Chefs to Japanese Knives

Published:

In honor of Women’s History Month this March, we’re resurfacing previously published features on women making an impact in the restaurant industry.

Every first-year student going into the Culinary Institute of America’s culinary program starts with a starter pack of eight knives: a set of different blades, each dedicated to honing a specific skill, whether it be breaking down fish to slicing a tomato so thin you could see right through it. But according to CIA alum and Bergdorf Goodman chef Adolfo Garcia, everyone in his year dreamt of owning one knife and one knife only: a knife from Korin.

A Japanese tableware and restaurant supply company founded in New York in 1982, Korin is regarded as the gold standard for Japanese chef knives by anyone working in the restaurant industry — not just in New York, but across the country, and even internationally to some extent, too. And behind the company’s influence and success lies Saori Kawano, a godmother of sorts to everyone in the industry as Korin’s 69-year-old founder and president.

Kawano is the kind of utterly gracious woman who will pat the seat next to her, so that a curious writer may sit close as she offers over three hours of her time for a peek at her life’s work. The kind who, by the end of the interview, handwrote your birthday to conduct a proper Chinese horoscope reading (a hobby she picked up from her mother), insisting on promises to visit soon.

“She’s kind of like the mom of all restaurants,” says Raymond Trinh, the co-owner of Sixty Three Clinton in New York’s Lower East Side. “She takes care of everyone, and she’s the most generous, sweetest person.”

“She’s also just a boss,” adds Trinh’s partner and chef at the restaurant, Samuel Clonts. “She pretty much became the leader of Japanese knives in New York City.”

To really understand Kawano’s unseen impact on the American restaurant industry, Korin’s resident knife sharpener Vincent Kazuhito Lau points to the company’s 35th anniversary in 2017, where former Union Square Cafe chef Michael Romano gave a memorable speech.

“He was saying that sometimes, on the ocean, it may look calm on the surface. But underneath, there’s a current that’s turning and moving the ocean, and that Saori is like that current underneath,” says Kazuhito Lau. “She’s moving and bringing Japanese culture and knives, all these different things. It was this huge movement underneath that people in the restaurant industry didn’t realize was happening until it surfaced.”

“And now, everyone’s using Japanese knives.”

As she tells it…

It all started when Kawano’s uncle, a professional wrestler, brought her back a souvenir from an overseas competition when Kawano was not even 10 years old: a placemat depicting New York’s skyline.

“Since I was very little, that was my dream, to go there someday,” says Kawano. “But I am a foreigner and cannot compete with American people. So, what is something I can do that no one else is doing?”

Sharing a piece of her cultural heritage was her answer. From the age of seven, Kawano diligently learned traditional Japanese art forms like floral arrangement, tea ceremony, and kimono wearing, preparing herself to make it to New York, one day.

An opportunity finally came in 1978, when her late ex-husband, Chiharu Sugai (whom many know as Korin’s original knife sharpening master — more on that later), then a contemporary composer, was eyeing Julliard in Manhattan. They left with a backpack, a tape recorder, one English-Japanese dictionary, and their wedding gift money to jump start their lives in New York. Kawano was 25.

The money dried up sooner than they thought, and for six months, Kawano and Sugai survived on Wonder Bread sandwiches of peanut butter and jelly, taking turns sleeping on the single bed of Columbia’s tiny International Center dorms they were staying in.

Kawano jokes that she got her start in the industry because she missed eating rice too much: With the promise of family meal, she got a job as a waitress at Nakagawa, a long-gone Japanese restaurant that mostly catered to Japanese expats on West 44th Street. The owners, Mr. and Mrs. Kameda, would sponsor her green card, and eventually become Korin’s first customers.

Having found some stability three years into the job, Kawano re-assessed her goals and dreams in the new year of 1982: What did she love? What could she do? There were obstacles: Kawano didn’t yet speak English fluently and not many Americans seemed interested in learning about Japanese culture — they weren’t even interested in the food. It’s unthinkable today, but four decades ago, Japanese cuisine wasn’t really on anyone’s radar in New York.

But after a phone call with her mother, she recalled her love of beautiful plateware and dishes, and an idea started to take shape: Maybe she could sell dishes to Japanese restaurants in New York.

It took her six months…

To save and send $2,000 to her old next-door neighbor growing up in Japan to purchase plateware (he worked for a wholesale tableware company). With the support of friends and coworkers, Korin launched in 1982 in a warehouse storage space on North Moore Street in what was then inexpensive and gritty Tribeca. Mr. Kameda, her first customer, purchased 1,200 teacups for his 120-seat restaurant, and told her to quit waitressing to focus on her new business.

Kawano would glean phone numbers from the Yellow Pages, carefully paging through the restaurant section of big East Coast cities for words like “Sakura,” “Ginza,” “Tokyo” — any kind of Japanese-sounding names. She would cold call them — “Mushi mushi!” — and hope someone would be interested in what she was selling. If they were, her husband would drive her to Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Maryland, and even North Carolina to deliver the goods.

Business slowly trickled in, but the number of Japanese restaurants accounts she had was limited, and her clientèle remained 100% Asian. That all changed in 1991 when a young chef with a heavy French accent visited her Tribeca warehouse in search of tableware for the opening of his French Thai restaurant, Vong.

His name was Jean-Georges Vongerichten.

Kawano stills remembers the day…

She met a then 33-year-old Vongerichten vividly. “He was so handsome,” she smiles. “His face was shining, like a boiled egg out of a shell.”

Vongerichten had initially gone to Katagiri, a Japanese grocery store that still lives on East 59th Street. Kawano was selling some tableware there, and it had caught Vongerichten’s eye. So, Katagiri’s manager told him about the lady behind the plates in Tribeca.

“He came to my humble, fourth-floor warehouse in Tribeca that no one visited,” recalls Kawano. “He was the only person who came, and it was a big surprise.”

“We were amazed at the collection of plates and cutlery,” says Vongerichten. “[Saori] didn’t even have a store yet!”

Vongerichten bought everything Kawano had in her tiny makeshift showroom for Vong, becoming her first non-Asian client. When Vong opened in 1992, Kawano was a frequent visitor. They became friends, and the whole experience was a lightbulb moment for Kawano.

“That was a very big turning point,” she says. “I wanted to have more [non-Asian customers] like Jean-Georges. But how can I approach them? No other Western chefs were interested in Asian cuisine or Japanese dishes back then.”

“But maybe,” she thought, “we could build a relationship with knives.”

And so began Kawano’s biggest challenge yet…

Introducing Japanese chef knives to a non-Asian audience. It was a fiasco at first. Chefs were more accustomed to the flexible and double-edged knives (which are sharpened on both sides) of Western brands like Sabatier and Wüstof, and they would chip their thin Japanese single-edged blades (sharpened on just one side, making them extremely sharp) purchased from Korin after a single use. They were “defective,” of “poor quality,” they’d furiously claim.

Kawano was at a loss. She had made sure to only source top-of-the-line knives that acclaimed chefs in Japan were using. She realized she needed to teach American chefs how to properly handle these singular and delicate blades. And so, Kawano went on a tireless educational campaign that would eventually take Korin seven years to turn a profit on.

It started with a knife catalog in 1995, the same year the store as it currently stands on 57 Warren Street opened. A small “how to” pamphlet of eight pages at first, it grew bigger and bigger, incorporating testimonials from highly regarded chefs (and Korin fans) like Vongerichten and Nobu Matsuhisa, finally becoming the glossy 160-page knife Bible it is today. More of an educational resource than a product catalog, it is a beautifully detailed and serious introduction to the world of Japanese knives and how to care for them.

Another key component of this educational campaign was Kawano’s ex-husband, Sugai.

Whenever a chipped knife was sent back in (and there were many in those days), the Korin team would have to ship it all the way back to Japan in order for it to be repaired. They were operating at a loss, but no one in New York possessed the skill. That is, until Sugai started training under many Japanese knife sharpening masters, including Shouzou Mizuyama, regarded as one of the best sharpeners in the world. Sugai opened a maintenance and repair service inside the Korin store, fixing and sharpening chefs’ knives right in Tribeca.

“He’s a big part of why I made it through the first few years in the city as a chef,” says Garcia. “That was my cheat code: Just bring it to him and your knife’s a razor.”

My friendship and working relationship with Saori is one of the things I’m most proud of throughout my career.— Jean-Georges Vongerichten

After countless lectures…

Knife sharpening demonstrations, and all those catalogs, American chefs started to take notice. They learned and converted, using knives from legendary makers like Nenox, Masamoto, Suisin, Misono, and even Korin’s very own private label brand. Kawano’s lightbulb moment more than paid off: Knives now account for 20% of the company’s business.

“Literally any kitchen you walk into in New York City will have a Japanese knife,” says Kazuhito Lau. It may have taken Kawano and Sugai over 15 years, but what he says rings true: Korin knives are ubiquitous and found in American restaurant kitchens far and wide.

In 2010, a then relatively unknown Marc Forgione (of Peasant and One Fifth) competed for (and won) Iron Chef with a Korin knife. Every night, Clonts uses his trusted Korin slicer for Sixty Three Clinton’s perennial crudo sashimi course. Sushi chefs from the East coast to the West, even in Dubai, use Korin knifes to meticulously slice their fish. And during Garcia’s time at Momofuku Ko some years ago, he claims the entirety of the Ko kitchen was a die-hard Nenox knife-using brigade, all lovingly purchased from the Tribeca store.

Sugai passed away in 2018, but his portrait still looms large above the knife sharpening station at Korin. That’s where you’ll find Kazuhito Lau most of the time, where he can sharpen up to 100 knives on a good day.

It’s serendipitous…

That Kawano achieved her childhood dream of making it in the city. Despite all of the hardships and trials, she’s successfully bridged cultures through Korin, not only introducing pieces of her homeland — to what is now a very receptive audience — but incorporating them into the very fabric of the industry, too.

“I deal with many different people, but I like the hospitality industry [the best], because their passion is genuine,” she says. “Chefs want to cook the best meal for the customers. It’s not about money; it’s about their passion and creativity. It’s the same with Japanese craftsmen.”

“It’s such an honor and a pleasure to be their neighbor,” says Forgione, whose namesake restaurant is a mere three blocks away from the Korin store. “The support that they show and the natural kind of respect that they have for us chefs and restaurants … We’ve just forged a really nice symbiotic relationship with each other.”

“It’s been great to see how she has grown her business and company, and we continue to work with her as she supplied plates for us at the Tin Building, our most recent project,” says Vongerichten. “I always recommend to friends or new chefs who join the team to take a visit to Korin — find the perfect chef’s knife and learn about her story and craft. My friendship and working relationship with Saori is one of the things I’m most proud of throughout my career.”

Still, Kawano wants to do more. When she first started in 1982, she had committed to being in business for 50 years. Today, 41 years later, she says her motivation is higher than ever.

She wants to pursue even more educational programs, like the Gohan Society, a nonprofit organization she founded in 2005. The society gives out scholarships to chefs based all over America to stage in traditional restaurants in Japan and learn about the country’s culinary traditions. She still very much vies to be that bridge, and branch out beyond knives and the nonprofit.

“I’m not interested in buying a big house or expanding Korin everywhere,” Kawano smiles. “I want to stay small as a company and be respected. I want to do a good job and connect people.”

“Sam [Clonts] actually took me to Korin on my first day in New York City,” says Trinh. “This was over 10 years now. I bought my first real knife as a nice welcoming gift to myself. It was a Misono UX 10, and I still have it. It felt like whatever is going to happen in the city is going to happen. But I was part of it, you know?”

Korin is open on Saturdays and Mondays through Thursdays from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Noëmie Carrant is Resy’s senior writer. Follow her on Instagram. Follow Resy on Instagram and Twitter, too.