The Long Road to Gage & Tollner’s Once-and-Again Return

Published:

Historically, there are no second acts for famous New York restaurants. Rector’s, Mama Leone’s, The Colony, The Quilted Giraffe’s, Maxwell’s Plum, Elaine’s — they all had their moment in the sun, some longer than others. Then the economy went south; or the fashionable crowd turned their pilot-fish attentions elsewhere; or the owner died; or tastes simply changed, and the institution, seemingly a permanent fixture, was unceremoniously ripped from the fabric of Gotham society. (Delmonico’s is the exception that proves the rule. New York’s first famous restaurant hop-scotched uptown, following its patrons, until it finally succumbed in 1923 at the corner of 44th Street and Fifth Avenue. Even today, it still exists in spectral form, connected to its storied past only by a name and one of the eatery’s many former addresses: 56 Beaver Street).

Gage & Tollner, however, has bucked this fatal history. The Brooklyn eating icon has managed to rise from the dead not once, but — owing to the pandemic, which shut down the city the very day in 2020 the restaurant was to open its doors — twice. That’s quite a Houdini trick for a restaurant that had been dormant for 17 years, made to suffer as shelter to transient squatters such as TGI Fridays and Arby’s while it awaited a proper rescue party.

That party turned out to be a trio of humble Red Hook restaurant and bar owners, including St. John Frizell (Fort Defiance) and husband-and-wife team Sohui Kim and Ben Schneider (The Good Fork and Insa). The tale of the discovery began with Frizell, who was compelled by his ongoing divorce proceedings to frequently visit the Supreme Court Building in downtown Brooklyn. Each time he exited the hall of justice, he wanted nothing more than a good drink. But gritty Court Street and grittier Fulton Mall had little to offer. Frizell saw an opportunity; downtown Brooklyn needed a proper bar.

Thereafter began a property search with an unlikely ending. After many a fruitless visit to various unpromising spaces, a broker led Frizell and Schneider down a suspiciously familiar block of Fulton. “Are they taking us to Gage & Tollner?” thought Frizell. They were. The magical space cast its spell and soon enough, a quixotic mission took hold of the two men.

They called Kim. “I send you boys out for a carton of milk,” she replied, “and you come home with a cow.”

▪️

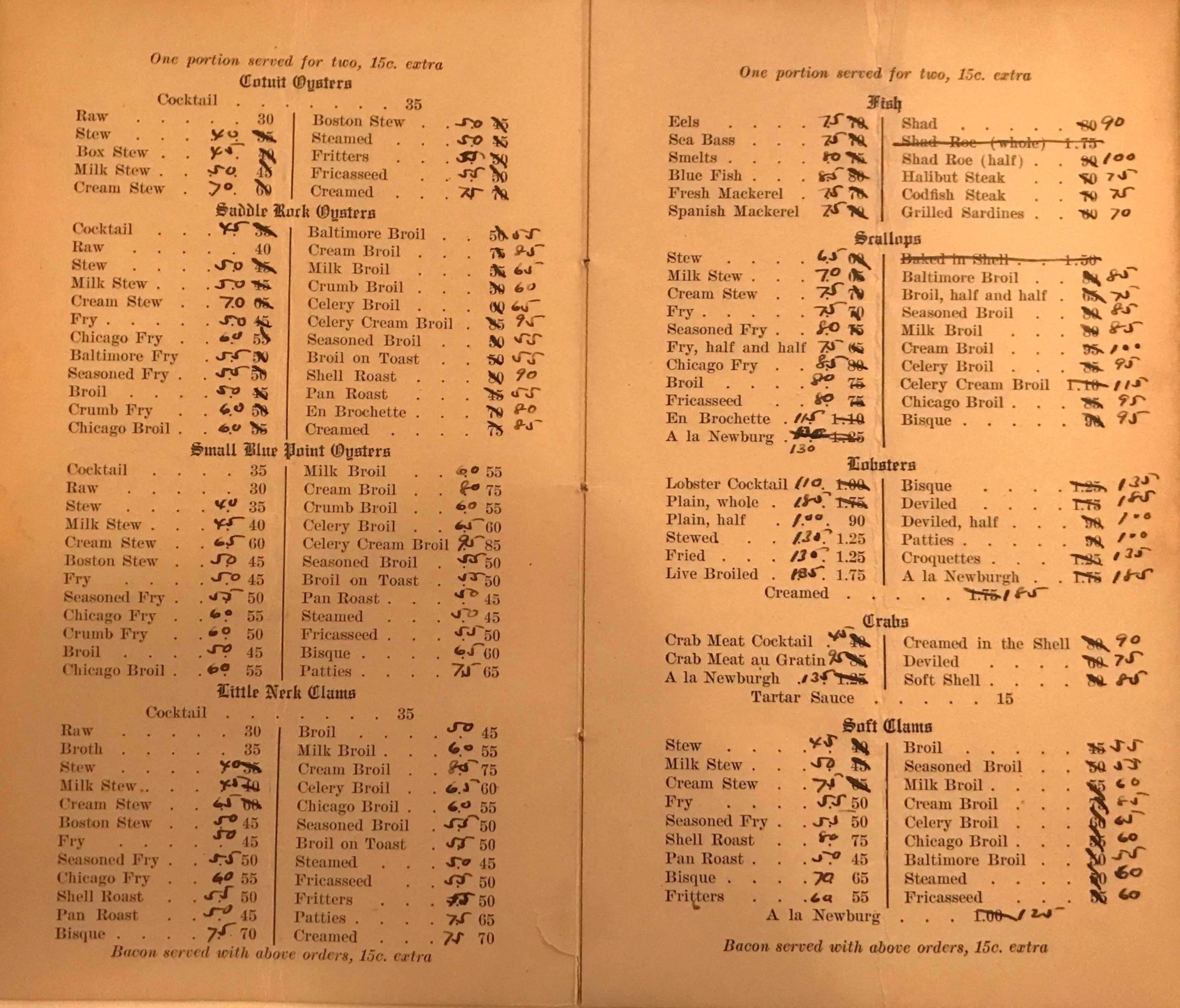

The long history of Gage & Toller begins with Gage, an oysterman. Charles M. Gage opened an eatery at 302 Fulton Street, a couple of blocks from its current location, in 1879 — when Brooklyn was still an independent city — before the “Great Mistake” of 1898, when it merged with New York. Eugene Tollner, a cigar salesman and a Gage regular, jumped on board in the 1880s. The two partners were evidently so close that Tollner named his son after his partner: Gage E. Tollner. Edward H. Gage, Charles’ brother, managed the place.

In 1892, the team moved the business to 372-374 Fulton Street, a building that stands on what was once farmland owned by Samuel Smith of Smith Street fame. There it thrived until Gage and Tollner retired in 1911 and sold the place to two gents named Alexander Hogg Cunningham and Marcus J. Ingalls. The new owners agreed to carry on in the oyster-house fashion of their predecessors. (As early as 1910, Gage & Tollner was referred to as “old-fashioned.”) Tollner, however, missed the daily swirl of society and soon un-retired. He became a fixture as manager at the restaurant. He died in 1935, at age 86, while boarding a trolley on his way to work. (Both Gage, who died in 1919, and Tollner are buried at Brooklyn’s grandiose Green-Wood Cemetery.)

The early decades of the 20th century were a time of celebrity patronage, when the restaurant attracted the famous players of Brooklyn’s nearby theater district. These included Lillian Russell, Jimmy Durante, Mae West, the great vaudeville team of George Walker and Bert Williams, as well as high-living theatergoers like “Diamond” Jim Brady. Given the restaurant’s proximity to the halls of government, it was also a favored watering hole to countless local politicians and lawyers.

The reign of Cunningham and Ingalls was short. Marcus J. Ingalls died Feb. 20, 1911, shortly after a meal in the restaurant. (He, too, rests in Green-Wood.) In 1919, surviving owner Cunningham sold the place to Seth Bradford Dewey. The Dewey family ran the restaurant longer than anyone, remaining in control until 1988, with John B. Simmons joining them as partner in 1973.

Gage & Tollner’s final great chapter began in 1988, when new owner Peter Aschkenasy hired renowned Southern cooking authority Edna Lewis, then 72, as chef. It was during this period that Gage slowly began to change with the times, with the clientele, as well as the staff, beginning to integrate; prior to the 1970s, the customer base was almost entirely white, while the waitstaff and kitchen staff, many of whom had tenures at Gage that lasted decades, were exclusively Black. The experiment, however, failed to reverse the downward fortunes of the restaurant, whose grand, Victorian ways were now badly out of step with the times. Final owner Joe Chirico bought the place in 1995 and spent half a million restoring the interior. But he couldn’t coax discerning diners to the now-scruffy stretch of Fulton. He closed shop in 2004. No restaurateur stepped up to take his place.

Then came the dark times. Gage & Tollner slowly descended through several humiliating circles of mercantile hell. A developer converted the private dining rooms on the second floor to office space. Occupants of the ground floor ranged from a TGI Fridays franchise to an Arby’s fast-food joint to a discount jewelry store. Until recently, one wouldn’t have been faulted for believing there was a better chance of the Dodgers returning to Brooklyn than Gage & Tollner.

But then Frizell, Kim and Schneider took the leap. Not having deep pockets, they raised the capital in a very new-fashioned way, through a $600,000 capital campaign on Wefunder, a crowd-funding service that allows investors with limited money to offer equity in entrepreneurial projects.

The trio were respectful of the restaurant’s rich lineage, both architectural and culinary, and worked hard to honor those traditions, while still keeping in mind that they had to attract a 21st-century audience. (With regards to the interior, the group had no choice but to be respectful; the space has landmark protection.)

To bring the interior back to life, the partners had to become experts in historical furnishings and accoutrement (all under the watchful approval of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission). Schneider, a master carpenter, designed tabletops and banquettes in keeping with the Gage style and had them built. He painstakingly dismantled and rebuilt the revolving door that anchored the frontage, with a little help from a revolving-door expert from the Midwest who may very well be the last of his breed. The crumbling portico outside was repaired and the mahogany-framed arched mirrors that line the room were refurbished.

Frizell did a deep dive into the work of legendary Victorian designer William Morris to zero in on the proper wall coverings, finally selecting a design called “Fruit.” Other disparate design inspirations for Frizell included the grand old Victorian homes of the Hudson Valley, such as painter Frederic Edwin Church’s ornate home Olana, and the Paul Thomas Anderson film “The Phantom Thread.” Broken and missing globes for the 13 brass chandeliers — arguably the space’s most recognizable feature — were replaced. “If you’re wondering if there are guys out there whose life work is Victorian glass,” said Frizell, “they definitely exist.” Just polishing the chandeliers took three weeks. (Once powered by both gas and electric, they are now all electric.)

Kim’s new menu is recognizably Gage & Tollner-esque, framed by lots of steaks, chops and seafood, albeit accented by recognizably modern touches. Oysters have been a keystone of the bill of fare going back to 1879, and they retain a place today. Clams on the half-shell, shrimp cocktail, chilled lobster and towering seafood platters, as well as a wedge salad and Baked Alaska also speak of the appetites of old. (The old Gage actually never served Baked Alaska; it just feels like they should have.) The she-crab soup, served with sherry, is a nod to Edna Lewis’ memory, as is the Edna Lewis Room, a private dining room on the second floor. But the twice-cooked cauliflower steak with salsa verde is something “Diamond” Jim never set knife and fork to; and the Oysters Rockefeller shares space on the menu with Kim’s Clams Kimsino, which is served with bacon and kimchi.

The drinks list, crowded with classic cocktails, meanwhile, draws on Gage’s original and copious alcoholic options, with a few exceptions, such as a Dirty Martini and an “improved” Harvey Wallbanger. The second-floor cocktail bar, the Sunken Harbor Club, however, is a completely new affair, built out by Schneider to feel like the galley of a ship and serving what Frizell calls “pre-tiki classics.” (Read: a lot of rum.)

So far, the public has responded to the trio’s loving efforts. Reservations have been hard to come by in the months since Gage finally opened its doors in April. A broad spectrum of Brooklynites have spun through the freshly revolving door, ordering steaks, hash browns, clam belly broils and Baked Alaskas in profusion. A pan of Parker House rolls adorns most every table. At the bar, it’s all about martinis, Planter’s Punches and Pink Ladies. The “very famous restaurant in Brooklyn,” a museum piece for so long, lives and breathes again.

“A lot of what I personally envisioned to be the experience to be is being fulfilled,” muses Schneider. “The sense of people having a wonderful time. It’s a great room for people to have a good time with each other. It’s luxurious without being fussy.”