From Lucille’s to Late August (and Beyond), Chris Williams Is Poised to Expand — and Uplift

At some point last year, Chris Williams was convinced the pandemic would destroy the business he built with his brother, Ben, a restaurant named for their pioneering grandmother, Lucille B. Smith.

Today, however, the Houston-based chef and restaurant owner of Lucille’s finds himself poised to not only come out of the pandemic stronger than ever, but he’s in growth mode. He is about to open two new restaurants in two different countries, including one in Houston with Dawn Burrell, a rising star who will be on the new season of “Top Chef.” He’s overseeing a growing nonprofit, Lucille’s 1913, which helps feed underserved communities throughout Houston. And next year, he’s planning to open two more projects in Houston’s Third Ward in collaboration with Project Row Houses, a public art initiative and community organization.

“I never thought we’d be in this place,” says Williams. “But this year gave me a lot of time — being down 92% in business [last year] gave me time to actually reflect and think about the business in new ways.”

- I Thought The Pandemic Would Kill My Restaurant, But It’s Only Made It Stronger

- Around a Table: My Hopes For These Historic Times

- For Black Chefs, Vegan Restaurants Mean Nourishment — and Empowerment

- Everything You Need to Know About MARCH, Opening Soon in Houston

- Meet Kaitlin Steets, the Rising Star Behind Theodore Rex’s Pop-Up, Littlefoot

- A Year in the Life of Restaurant Workers

What Williams built over the past year, and what he continues to build, is what he describes as a sort of “vertical ecosystem” consisting of the restaurants and the nonprofit — all sharing the same goal: supporting the local community and uplifting the Black community, especially.

“These programs and these restaurants we’re doing — every single thing is meant to benefit or contribute to the sustainability of the work we’re doing at Lucille’s 1913, or to Project Row Houses,” he says. “That’s what’s really driving me right now. I just want to continue to grow the Lucille’s Hospitality Group and grow our message, to showcase the diversity and the beauty of different people working together, and what can really come out of that.”

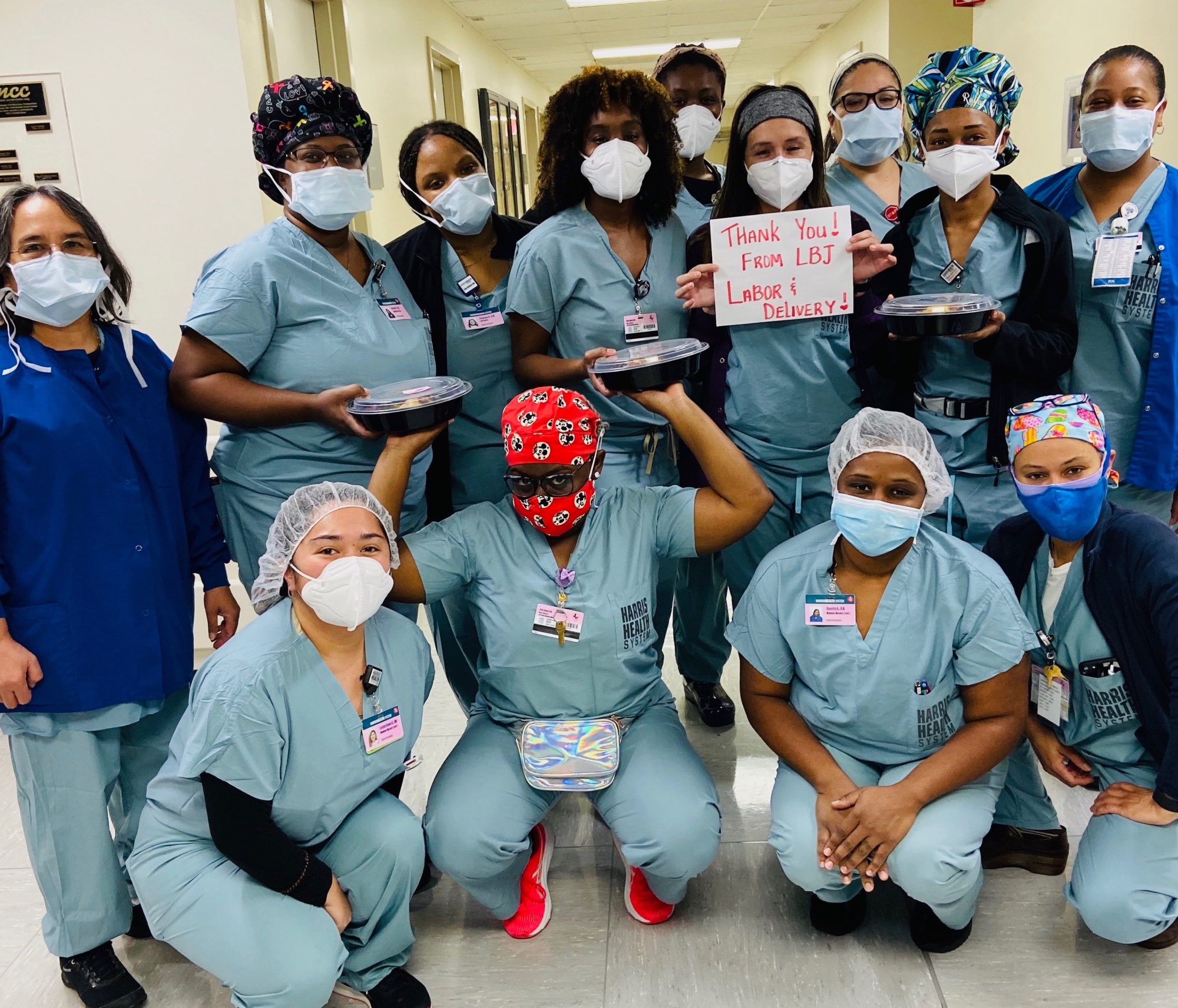

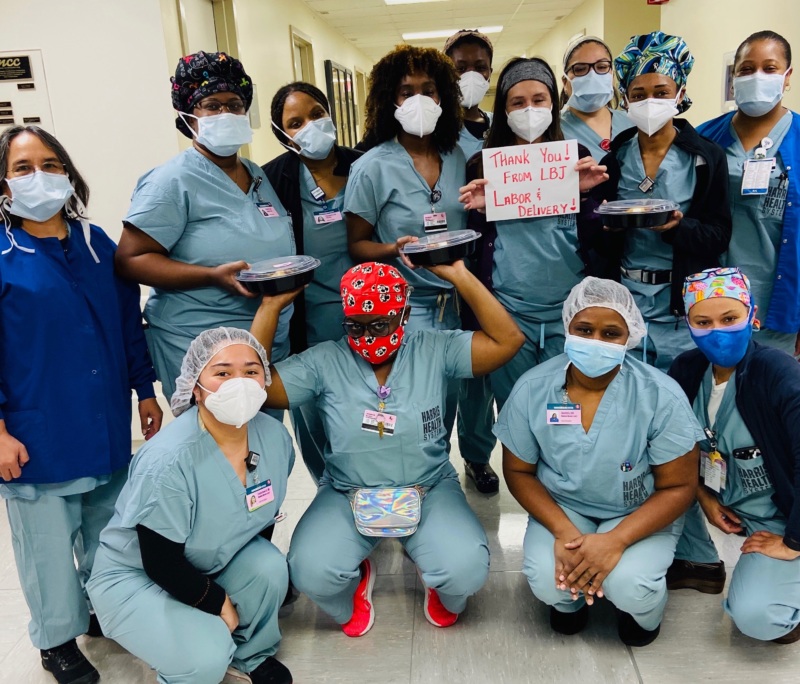

Williams saw that power first-hand in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. When COVID-19 shut down restaurants and bars across the country, he kept Lucille’s open by delivering thousands of meals to local frontline hospital workers. Eventually, they shifted to feeding those in underserved communities throughout Houston — work they still do today as a part of Lucille’s 1913.

All this community outreach ultimately convinced Williams to start Lucille’s 1913 in July. And it’s only grown since.

Today, Lucille’s 1913 delivers more than 700 meals daily to underserved communities in Sunnyside, Acres Homes, the Fifth Ward, and the Third Ward, and to the Imani School from its separate commissary in Southwest Houston. A second kitchen, located in the Fifth Ward, recently opened, and there are plans to open four more kitchens in the near future, as well as to have 52 acres of land devoted to farming.

The kitchen sites double as community centers where children and the elderly can learn about gardening, cooking, and eating nutritiously, too. And Williams expects both the kitchens and farms to generate approximately 120 jobs for the local community, too. “We’re trying to provide opportunities to find a sustainable livelihood through the medium of food, and all of its parts, from farming to fermentation,” says Williams.

Before the pandemic, Williams says he employed 42 people. Today, he employs 80 and counting.

Funding all of this community outreach are the profits made from Lucille’s, and soon, two new restaurants.

The first to open this year, in June, is Emile’s Black Point Bistro in Nova Scotia, Canada. It is a restaurant that Williams has been working on opening for the past three years and was initially supposed to open in 2020. There, Williams is reimagining a family-owned restaurant from two Lebanese-born immigrants, Emile and Samira, that’s been a part of the local community for the past 45 years. With the family’s blessing (the family still owns the building), Williams is reopening the restaurant as a local pub that celebrates the seasonality of Nova Scotia’s local ingredients and pays tribute to the family’s Lebanese roots.

Williams says he wanted to open Emile’s mostly for his two sons, ages 11 and 13, who live in Nova Scotia with his ex-wife. “Canada is lovely, but if anybody knows anything about Canada, it’s that there aren’t very many opportunities in the Black community, and even less when you’re talking about ownership,” Williams says. “I’ve been actively trying to find a way to bring what we do to them, so they can have access to that, in spite of their environment.”

The second restaurant, slated to open in late summer, is called Late August, to be helmed by chef and partner Dawn Burrell, who was most recently the executive chef of Houston’s Kulture. Before becoming a chef, Burrell was a 2000 Olympian, and she is also competing in the next season of Bravo’s “Top Chef,” airing next month.

Williams said he has always admired Burrell’s talent as a chef, and that when she returned from filming “Top Chef” last year, he could think of no one better than Burrell to lead the kitchen at Late August, which will focus on Afro-Asian cuisine, combining the flavors of West Africa with techniques from Asian cuisines.

“She’s the only living person I know on the planet who has become a master of two separate things in one lifetime,” says Williams. “She mastered track-and-field to make it to the Olympian level, and she’s a James Beard-nominated chef finalist. And then to be on ‘Top Chef,’ I mean, it’s incredible. I hope people know they’ll get to see a true master at work when they go to the restaurant.”

Next year, two more concepts, which will also benefit Project Row Houses, are slated to open in the Third Ward. The first is Rado Café, a community market and café serving coffee, wine, produce, and healthful foods, named for the historic Eldorado Ballroom in which it will be housed. Next to the café will be the Hogan Brown Gallery celebrating Black art and artists. Project Row Houses is currently renovating the historic ballroom, which was a nationally renowned showcase for Black entertainers, first built in 1937.

“We want to take it back to that 1937 graduating class, and put in 2030 sound, sound for the next decade,” says Williams. “This is going to be a place where we showcase true real music and music in Houston in a place that’s in the neighborhood, for the neighborhood, and for the community.”

He says he sees the revitalized ballroom becoming a gathering place that stems the tide of gentrification making its way into the community. And he’s also excited to see what opportunities will emerge for young Black artists and musicians, too, from the project.

“I think Black people have woken up to their own socioeconomic power, the power of their dollars, and how much industry is created just to capture their dollars, but that it’s not always created by them,” he says. “And so, for them to wake up and redirect their money into their own community is huge, because that’s what every single other community, in this country and in the world, has, right? That’s how you build up your voice, and that’s how you can really have a real impact and change is by owning your own first.” Still, he adds, “There’s still a lot of room to grow.”

When I asked Williams if he’s at all worried about stretching himself too thinly, with so many projects and initiatives, he’s quick to point out that he couldn’t do all of this without help from others, like chef Burrell, and like his founding chef/partner Khang Hoang, who now oversees the kitchen at Lucille’s as the chef de cuisine and has been with him since day one. Or Lawrence Walker, the culinary director of Lucille’s 1913, who has helped Williams deliver more than 150,000 meals to Houstonians in need. Or Robertine Jefferson, the director of development for Lucille’s 1913, who helps him run the nonprofit. Or Josh Lopez, the general manager of Lucille’s. Or Peter Clifton, the beverage director for all their concepts.

“We have this wonderful plethora of colors who are all working together, who are all about giving back first–we all do that work first,” says Williams. “And then if we make some money, it’ll be on the way back in, but it’s an investment of time and resources. And these are people, like I said before, who are a lot smarter than me, so no, I don’t feel stretched thin at all.”

He also hopes that when diners choose to dine at Lucille’s, Late August, Emile’s, or Rado Café, they’ll understand the kind of experience he and his team are trying to deliver not just to them, but for them.

“You’re going to be able to get history, you’re going to be able to have fun, you’re going to be able to see some dynamic talent from chefs like chef Burrell and chef Hoang, but the best thing about it is you have the opportunity to enjoy yourself with these things and know that your dollars have two purposes,” he says. “It’s not only sustaining the business but it’s going back into the communities, to your neighbors, and it’s bringing dignity back to these neighborhoods that have been forgotten.”

To learn more about Lucille’s 1913, and how to help or volunteer, click here.

Deanna Ting is a Resy staff writer. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter. Follow Resy, too.