Amid a Pandemic, One Restaurant Rediscovers Its Roots

Before the forced restaurant closures, the shelters-in-place, and everyone’s entire social network trying their hand at making focaccia, a small Long Island City dining room was packed to the brim and bursting with energy.

Adda Indian Canteen, the critically-acclaimed regional Indian restaurant, was living up to its name. Amid tabloid-papered walls, customers from Queens, Brooklyn, and well beyond were sharing seasonal saag paneer, with its cheese made in-house; goat brains as creamy as scrambled eggs; biryani, fragrant as it released its steam; the fiery Rajasthani curry known as junglee maas. While owner Roni Mazumdar and chef-owner Chintan Pandya’s first restaurant in the West Village, Rahi, was a modern and interpretive spin on Indian cuisine, Adda was an uncompromising interpretation of how, and what, India actually eats.

New Yorkers from all over had been trekking to Adda for what Mazumdar calls “unapologetic Indian food.” And it wasn’t just Long Island City locals, or the Indian-American community that came out. Tables were packed with all manner of diners.

That was then, of course. What happens when a pandemic forces restaurants such as Adda and Rahi to close? For Mazumdar, the crisis surrounding Covid-19 crystallized the very nature and calling of his establishments, as community-driven havens where people could connect with, and take care of, each other.

“When we started Adda, we never knew it was going to be nationally known,” he says. “We thought we were only serving the community.”

That original sentiment provided a north star for Adda and Mazumdar’s team during the crisis — one that began as soon as the March 16 order from Gov. Andrew Cuomo for all New York restaurants to shutter their dining rooms. There were economic concerns, of course, but more than that: The governor’s order, necessary as it was, effectively cut off neighborhoods from their cherished public spaces. “I felt like someone popped a balloon, and the air just went out,” Mazumdar says. “All that noise, all that energy, one day, just disappeared in thin air.”

The team debated whether the right move was to close, or to continue and adapt to the new realities of the pandemic. It was at this moment Mazumdar found himself thinking once again about the original reasons why he’d opened Adda: to serve its local community. “Is my purpose just to sell food, earn money?” he recalls thinking. “Or was there a bigger purpose of why we all started?”

The first step was to shift to takeout and delivery. To help stop any spread of the virus, Mazumdar and Pandya planned how they would cut back to a skeleton crew. “The first few days were a blur,” Mazumdar says. “Every hour, I would make a plan. By the next hour, literally, the plan would change. As restaurateurs, we’re always building the bridge as we’re walking on it. This time, we had to learn how to fly.”

They reduced staff, and devised a pickup system to transport all employees to and from the restaurant, by carpooling in one of the employee’s cars. Employees have either voluntarily taken a pay cut or refused salary entirely. In turn, Adda devotees from all over the city came in to order food and support the restaurant.

But a next step came when Off Their Plate, a Boston-based grassroots organization that feeds frontline healthcare workers, got in touch. They wanted to know if Adda would be their launch partner in New York.

“It was a no-brainer,” Mazumdar says. “Within 48 hours of that, we already had food going out of our kitchen.”

Meals that can travel

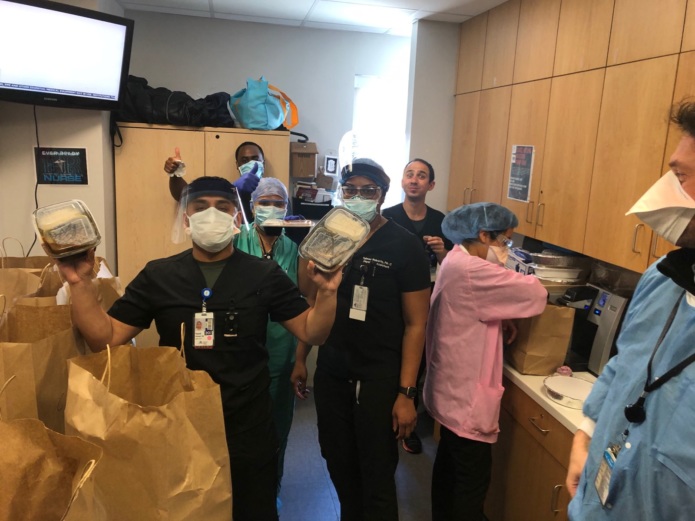

Since then, both Adda and Rahi have provided free meals to a network of hospitals in the city in partnership with the Boston group, as well as World Central Kitchen — including Mount Sinai, NewYork-Presbyterian, NYU Langone Health, and Elmhurst Hospital Center, the last being one of the most severely impacted hospitals in the city, serving a significantly foreign-born population. The restaurants have catered two to three times a week, offering between 50 to 100 meals each day.

The meals are simple, nutritious, and comfort-driven: butter chicken or chana masala (chickpea curry), served alongside naan, rice, and a samosa. “Indian food travels very well and tastes even better a little bit later,” says Mazumdar. In other words, perfect for doctors and nurses to reheat in the middle of a shift. The reception has been overwhelmingly positive. Now Mazumdar and his partners are discussing an expansion beyond hospitals, to also help hospitality workers displaced by the shutdowns.

“There’s a lot of people hurting out there, and in our tiny little way, we actually have the ability to make a positive impact,” says Mazumdar.

This is, of course, a story that has been told about many other restaurants — all struggling to figure out how to survive on the long road back to service as usual. But Mazumdar keeps in mind the importance of a restaurant staying focused on its backyard — no matter how much national attention it has received.

“I think we realized there’s a bigger calling,” he says. “The whole purpose of a restaurant is to serve. That’s why we create these things. It’s the fabric of a neighborhood, and the day the community needs you, you can’t disappear… So as long as it’s humanly possible, we will continue.”

Noëmie Carrant is a Resy staff writer. Follow Resy on Instagram and Twitter.

Discover More

Stephen Satterfield's Corner Table