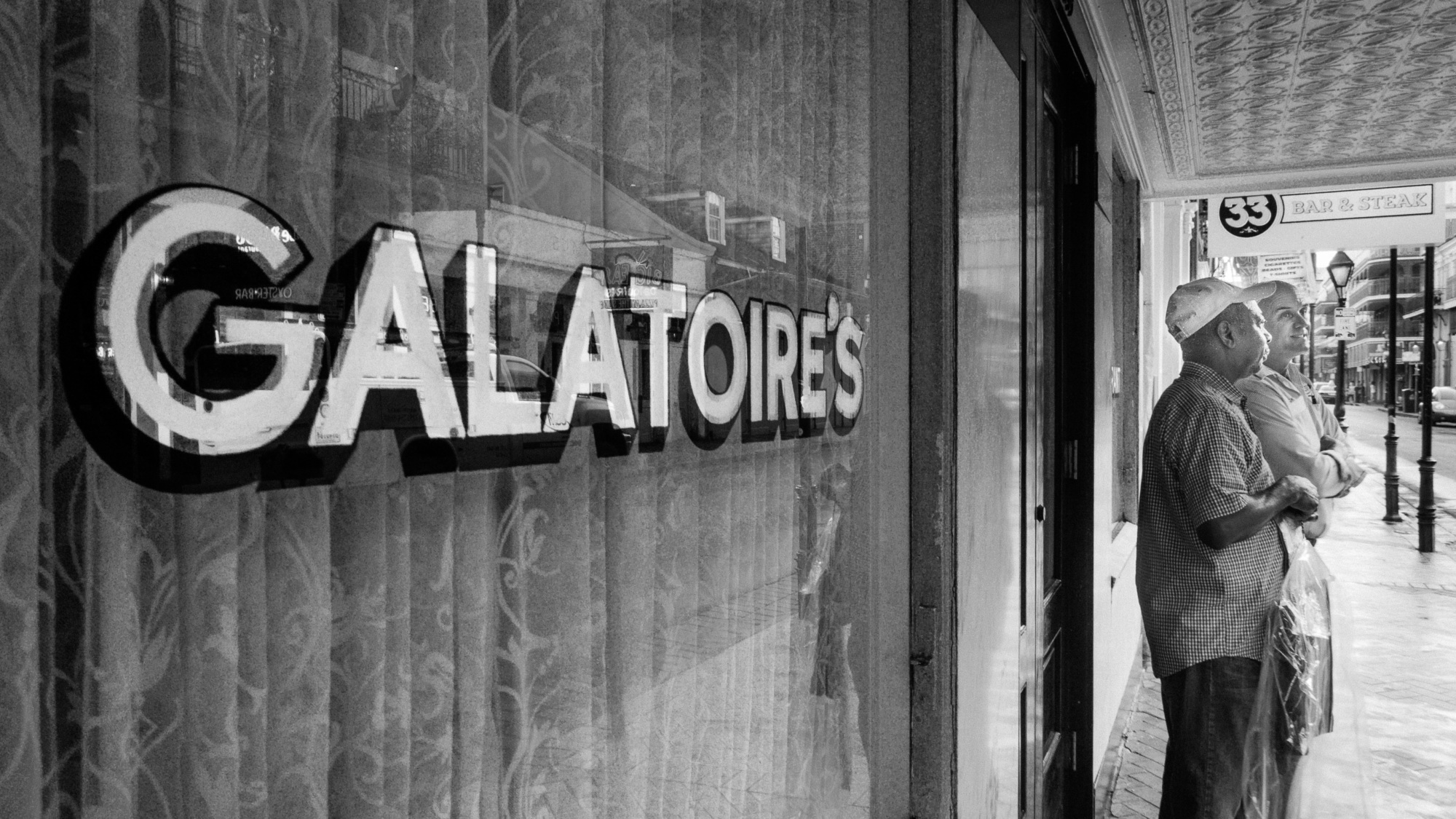

Vigil Mass, or, A Friday Lunch at Galatoire’s In the Midst of 2021

I was halfway through my pompano when a man in a gray wool suit stood up from his table along the mirrored wall and began to play the trumpet. In from Bourbon Street, a brass band filed to join him, raising their trombones above the rhinestone crowns of the women celebrating a birthday, angling their tubas between large men who’d pushed out their chairs. Galatoire’s was packed that day, Friday lunch a week after the plague had temporarily abated, and months before Ida would wallop the city — and the bayou communities to our south — hard.

All the tables — and then some — had been brought back in. The drummer kept his elbows tight, laughing as he passed the trumpeter in the fine gray suit. “Do What You Wanna,” they were playing, a Rebirth tune.

Friday lunch at Galatoire’s is ritual and reunion. As server John Fontenot, a 54 year veteran of the 116 year-old restaurant, once put it, “It’s like going to church; you meet all your friends.” When John was hospitalized with COVID during 2020’s awful spring, the whole city worried, reading newspaper updates aloud to each other over the phone. But he was there that day, a bouquet of wine glasses in his hand, as was Alicia, a waiter who trained under the waiter depicted in a photograph of her birthday party at Galatoire’s the year she turned eight.

Really, everyone was there: football matriarch Olivia Manning, and my cousin John, and the ghost of Tennessee Williams, and the ghost of my mother’s first dinner date, who dropped an oyster in the water carafe because she’d dropped an oyster in the water carafe, and a wine distributor my husband knew, and the family friend I once asked to prom. (He turned me down.) No one had seen anyone in a year, and everyone kept standing up to kiss each other on the cheek, spilling lapsful of French bread crumbs onto the mosaic tile.

Inside this city-wide reunion, we were having a reunion of our own. A friend who’d left us for a big new job in Los Angeles had, for a minute, come back after a whole pandemic year alone, and there was no question about where we’d eat. Galatoire’s was where we’d met, all six of us, a motley crew of New Orleanians new and old, brought together by a garrulous mutual friend in a jungle-print silk blouse and by Galatoire’s itself, its constancy amid the whirl.

As the only native in the group, I performed the rites: Ask for a favorite waiter — Billy Fontenot, this time, John’s brother — and wave the menus away. A Galatoire’s lunch begins with hot French bread torn on the white tablecloth and a cocktail — I always have a brandy milk punch, but a Sazerac, a martini, or a Shirley Temple are all allowed. Next come the fried eggplant batons and pommes soufflés, served with Bearnaise and powdered sugar, which you must mix into a pink Tabasco flurry on your plate. Then, there’s wine and appetizers: creamy crabmeat maison, shrimp remoulade, oysters en brochette, wrapped in bacon and deep fried.

While these circled, we talked about the long year: pregnancies and bereavements, a new job conducted entirely from a very old couch, a brand new baby none of us had met, illnesses of the body and the mind. Eventually, though, the day began to swell beneath the spinning ceiling fans. We lost track of worries, to-do-lists, families, an hour, maybe more. The mirrors that wrapped the room amplified the crowd, echoing the constant singing of the birthday song, and our glasses were always full, the wine cold. Only once the plates were empty was it time to order lunch.

Billy Fontenot, John’s brother, stood, folded linen napkin over the black sleeve of his jacket, and told us what we should eat. The pompano was very nice that day, as was the drum, and the soft-shell crabs were still kicking—have them sauteed, maybe, sauced with beurre blanc and jumbo lump. I ordered the pompano, and it arrived slick with meunière, just as it always does. Then the man in the sharp suit stood up and began to play.

Do what you wanna, the trumpet said.

I have a policy to give generously in return for anything that brings me joy. But standing up in the middle of such a lunch, in the middle of such a crowd, in the middle of a pandemic that you want to believe is over but is not—you can imagine—can be a challenge. I stood in my heels and staggered, clutching cash, between the tight packed tables, ducked beneath a tray of soufflé potatoes and shimmied into line between the snare drum and the trombone, found the bucket, tipped the men. Sitting back down, I realized I was shaking. From across the table, our long-lost friend reached out his glass for a toast, tears in his eyes.

“I missed this — What is this?” he said. “Why is New Orleans the only place that makes sense, except it doesn’t make any sense at all.”

I thought about it. Honestly (I wrote a book about Katrina) I think about it a lot. About our city’s excess and our joy in it. About that epithet, “the city that care forgot,” which means a couple of very different things. New Orleans knows, better than most places, about precarity. Floods, fires, plagues—we’ve been there, done that.

“We’re all going to die —” I raised my glass to him, clinked. “— so we live. We have lunch. You want some of this fish?”

C. Morgan Babst is a New Orleanian and the author of The Floating World.

‘As Beautiful As It Ever Was’: Chef Nina Compton Says It’s Time To Return to New Orleans

When Hurricane Ida hit New Orleans, chances are you likely saw photos of an empty French Quarter. Or footage of…

‘We Have to Continue Sowing the Seeds’: Alon Shaya on New Orleans After Ida

The big event that Alon Shaya had planned for August was the opening of his restaurant group’s first hotel property,…

Discover More

Stephen Satterfield's Corner Table