At the Heart of L.A., Harold and Belle’s Preserves a Legacy and Looks Ahead

Updated:

Ryan Legaux says that he’s probably eaten more po’ boys than most people alive. Having at least three or four sandwiches a week for the last 40 years at Harold & Belle’s in Jefferson Park, he just might be right.

Now the third-generation owner of his family’s historic “New Orleans in Los Angeles” restaurant, Legaux is down to maybe one shrimp po’ boy a week. But every morning he still heads to the kitchen for his must-have: A cup of classic filé gumbo — a savory blend of shrimp, blue crab, ham, sausage, chicken, and ground sassafras. Relishing the meaty dark roux alone, peacefully dipping a spoon into a cup, is as close as he gets to meditation.

Those precious moments are few. In addition to running the restaurant at the restaurant with wife Jessica, the two also have a food trailer that they use for events, Harold & Belle’s To Geaux. Pepper in teaching online cooking classes — Ryan has showed 400-plus people how to make jambalaya for the UCLA Fowler Museum Global Cuisines series — and providing meals donated by patrons to a slew of charitable causes, and things are busy. During the pandemic lockdown, Harold & Belle’s fed staff at Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital; senior citizens via District 10 and City of Los Angeles programs; various COVID testing sites; and the Orange County Labor Federation. They also regularly provided furloughed staff with take-home meal kits containing fresh vegetables, pasta, red beans and pinto beans, snacks, and toys and juice for kids.

“You don’t know specifically what people are going through. Some of our staff are very private,” Legaux says. “For the meal kits, we wanted things that traveled well, that people could make at home, and we took a trip to Mattel to pick out toys for their kids.”

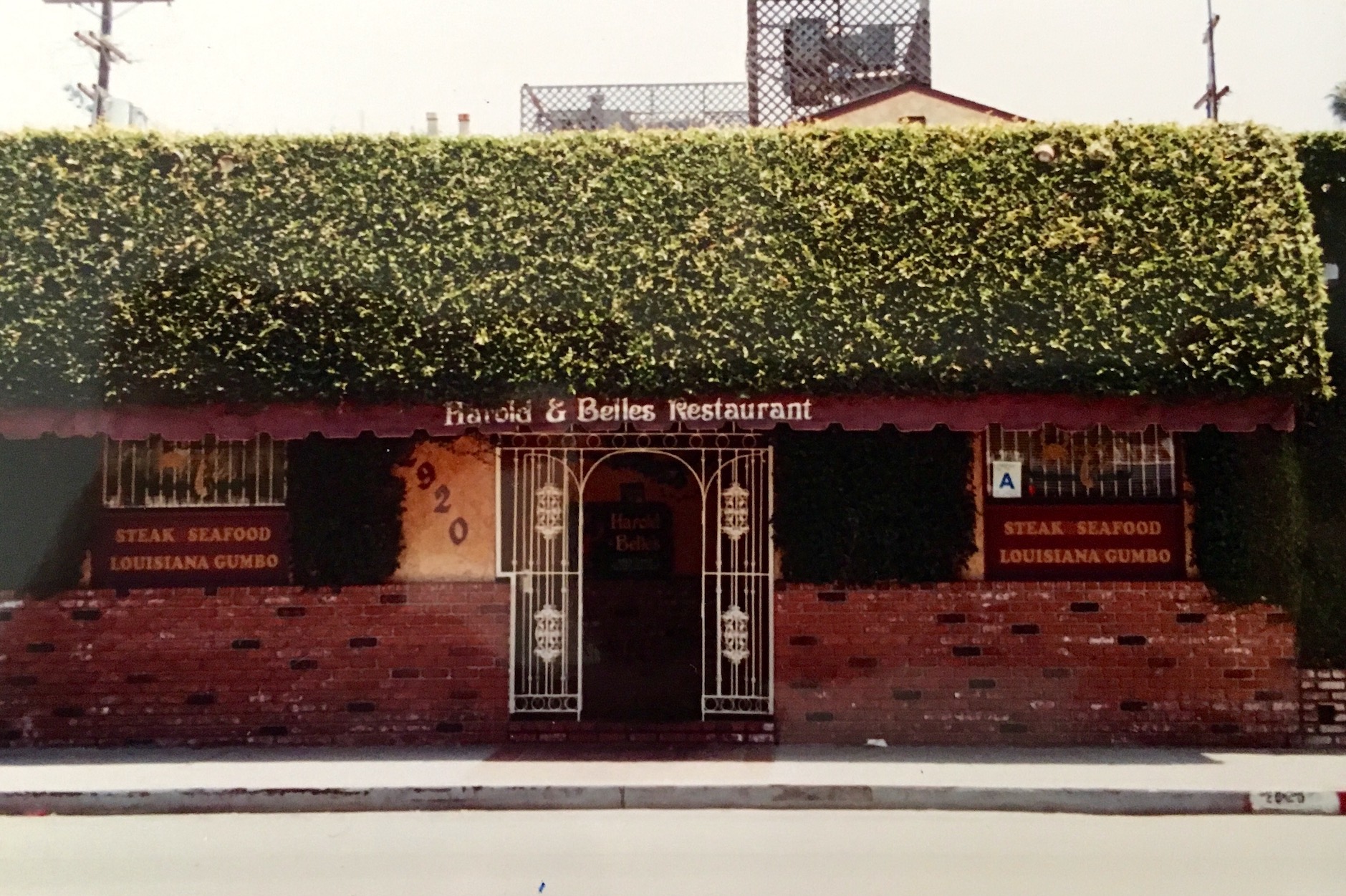

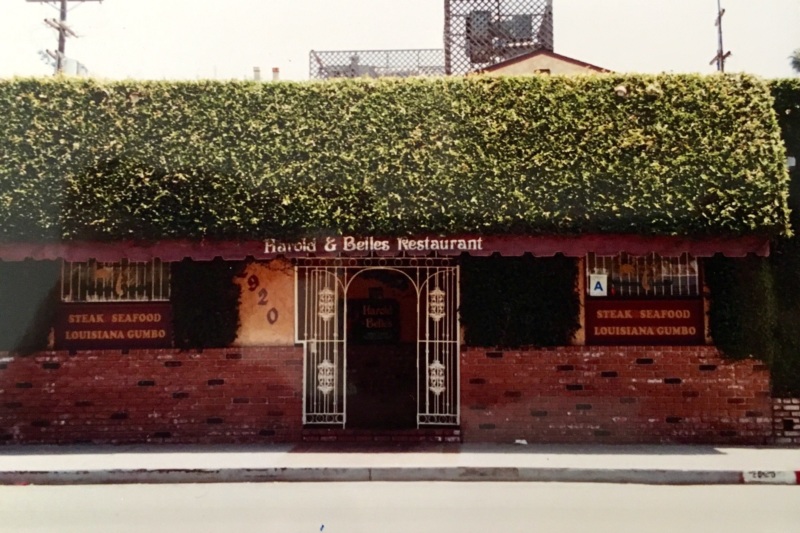

That community spirit, going the extra mile, is woven into the fabric of Harold & Belle’s. When his grandfather, Harold Legaux Sr., opened the place with his wife Mary Belle in 1969, Jefferson Park had become a welcoming berth for Black Southern transplants moving West during the Great Migration. He wanted a place for New Orleans expats to gather, blow off some steam, and feel like they were home.

After serving in the Navy during World War II, Legaux Sr. and Belle left New Orleans for L.A. in search of new opportunities. A “serial entrepreneur,” as Ryan calls him, his grandfather operated a bike shop, a Texaco franchise, and worked as a painter before opening the restaurant; his grandmother worked in the aerospace industry for McDonnell Douglas.

The two took over a former bar, named it Harold & Belle’s, and focused more on the pool table, jukebox and go-go dancers — not the food, the younger Legaux says with a chuckle. Still, customers loved the gumbo, po’ boys, and red beans and rice his grandfather served on Fridays. It’s what the place became known for.

“Not only is our restaurant a piece of family history, but it’s also American history,” he adds. “Creole is the only cuisine that was truly born and bred in the United States, so it means a lot to carry on that legacy. Since it’s a representation of culture, we try to keep it as authentic as possible, though authenticity changes over the years. People that come from the South still say we remind them of home.”

When Legaux’s parents, Harold Jr. and Denise, took over in 1979, they made it more culinary-oriented. As an adult, Harold Jr. enjoyed dining in Beverly Hills, and wanted to recreate that same upscale environment for a neighborhood that offered little like it. He expanded the dining rooms and added some decorative flair. When Legaux looks at old photographs of the restaurant, he sees the influence of 1980s Beverly Hills — the pink tablecloths and wicker chairs especially — and is proud of what his father created.

Even without COVID pivots, keeping the trust of loyal longtime patrons while innovating has been a constant challenge for the Legauxes. Since taking over in 2011, they carefully made adjustments, like remodeling the restaurant and minorly tweaking the menu. When it comes to the recipe book passed down by his father, their “strong suit” as Ryan calls it, he didn’t need to fix what wasn’t broken. The core recipes that helped give Harold & Belle’s iconic status remained, but something as small as removing yellow food coloring from the potato salad caused a backlash.

“People said, ‘Why did you change the recipe for the potato salad,’ and I said, ‘I didn’t, I just took out the food coloring that had no nutritional value,’” Legaux said. “But because of [our regulars], we never had to worry during the pandemic that we were going to close. They have been coming here a long time, even when people from Culver City and Santa Monica were afraid to come here. So you have to do right by them when it comes to changing a dish or raising prices. We have a responsibility to run a profitable restaurant because of all the people who count on it, and sometimes you have to make decisions not every customer is going to like.”

When Harold & Belle’s opened in 1969, Jefferson Park — in particular, Sugar Hill — was a long-established Black middle-class neighborhood with a corridor of Black-owned restaurants along Western Avenue. Establishing a Black community took effort, considering the racial covenants white residents employed to prevent Black residents from entering the neighborhood. The legacy of that residential segregation drew a firm line of inequality in that eventually led to pivotal events of social and economic unrest, including the 1965 Watts rebellion and the 1992 Los Angeles uprising.

Harold & Belle’s served as an informal community center from the start, as a pivotal safe space where Black residents could congregate, enjoy a drink, and play a game of pool. But soon after opening, the neighborhood was on the brink of hard times. The 1973 recession, as well as poverty, gang crime and home disrepair, began to have a toll on the bedroom community, leading to the closure of many Black-owned businesses.

“Where we are, for years and years, this was known as the food desert. You literally could not find a sit-down restaurant within a three-mile radius,” Legaux says. “It was rare for people of color to have a big, proper, fine-dining restaurant. Our community [still] has very few spots to celebrate your life events, from birthdays to anniversaries to graduations.”

For five decades the restaurant thrived while many other Black-owned restaurants closed across the city, especially high-end ones. Legaux says that when he looks at a vintage 1990s guidebook of high-end Black-owned businesses, Harold & Belle’s is included with about 15 other others, but only three or four are still in operation. He appreciates that the restaurant has maintained its status as an upscale, celebratory gathering place for the Black community.

It continues to be a favorite for local politicians and community leaders, a place for celebrations — including the annual Mardi Gras blowout that takes over the entire parking lot (with the exception of this year) — and a magnet for neighbors as well as L.A.’s entertainment and sports elite. Photos of famous guests line the walls, including one of Rosa Parks, who paid a visit in 1992.

That connection between New Orleans, Los Angeles, and the Black community is the cornerstone to what Harold & Belle’s is today. In thinking about the recent Black Lives Matter movement, Legaux hopes that the restaurant can foster a healing capacity similar to other famous New Orleans restaurants, like Dookie Chase’s.

“That place was known for bringing both sides together to work out civil rights issues and things like that,” he says. “While this isn’t the 1960s, a lot is happening on the political end, and a lot of times that gets discussed here.”

As they look to the future, the family is expanding the To Geaux brand, with a ghost kitchen to serve Louisiana-style plant-based menu (Jessica has been vegan for six years). They’d like to expand even more but remain cautious.

“The way we operate, we’re kind of hands-on,” Legaux says. “We only have one shot at it. The same goes for a lot of Black and brown entrepreneurs, who may only have one chance to get that loan or investor, and who can’t fail and make mistakes the way a billionaire could.”

“We’re adjusting to the times the best we can, but not getting lost in what’s trendy,” he adds. “This is L.A. and there’s always going to be something new and exciting and different, but you need to be true to your restaurant and your core values as an owner.”