How Black Women, and Black Imagination, Are Reshaping Italian Cuisine in the South

Published:

When chef Deborah VanTrece thinks about her time in Italy more than 30 years ago, she calls to mind the sparkling Adriatic Sea, vista views of Pescara, and the cobblestoned streets lining the medieval buildings of Siena. Her time there was transformative, changing the way she looked at life, connection and eating. It was also creative fuel for her latest restaurant, La Panarda, which was recently named one of Atlanta’s top new restaurants.

But experiencing Italy from that vantage point is only part of the story on the menu at La Panarda, because VanTrece also leans heavily on something even more important: her own culture, Southern experience, and Black imagination.

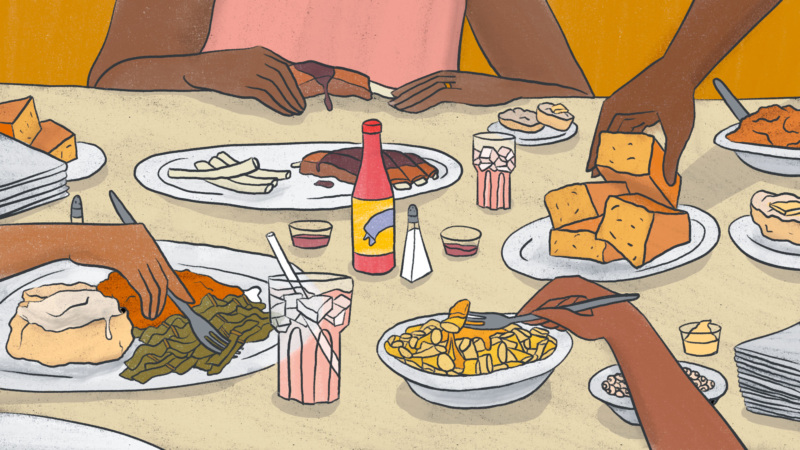

The connections between Italian and Black culture were glimmers that felt rooting for the restaurant — large, communal gatherings centered around food, recipes passed down from generation to generation, warmth over a table, and conversations that seem to always endure.

This cultural crossover is seen throughout the South. Take, for example, the many renditions of Black spaghetti — think baked spaghetti; saucy spaghetti made of ground beef, onions, and peppers; meatless spaghetti served up with fried catfish in parts of Mississippi — and the beloved role that fettuccine alfredo plays within the Black community. In many ways, it’s no surprise that both cuisines are steadily in conversation with one another.

This cultural crossover is seen throughout the South … In many ways, it’s no surprise that both cuisines are steadily in conversation with one another.

VanTrece is not alone in her innovation as a Black woman chef either — Tiffany Derry of Top Chef fame is slated to open an Italian restaurant named Radici in Dallas later this year. When asked why she felt called to this venture, other than her business partner’s influence, she reflected fondly on six years working in Italian restaurants at the beginning of her career.

The Black Italian in Louisville, owned by wife and husband duo Paula and Anthony Hunter, was created in homage to their daughter and her combined Black and Italian heritage. Dubbed as “Italian soul,” diners can expect smoked marsala mushroom pasta and their ever-popular “spalletti” — spaghetti sautéed in a blend of olive oil and cheese.

Roughly 300 miles south in Greenville, S.C., is White Wine & Butter, the city’s first Black-owned restaurant featuring Cajun and Creole Italian entrées. There, chef and owner Michael Sibert creates classic seafood gumbo with build-your-own pasta bowls starring housemade pasta with a variety of sauces and proteins.

As a former flight attendant, travel has always been a place of reprieve and creativity for VanTrece. But in her exacting amount of intention that she pours into all her restaurants, VanTrece created her newest restaurant as a way for guests to put one foot into Italy — right from the Southside of Atlanta.

“I wanted to interject, if you will, some of my old traditional food with Italian food,” she said. “Cross the two together. With the things I can find in the South. What the local farmers were offering. That was inspirational. My soul food background played a role in inspiring this menu.”

Found in Cascade Heights, La Panarda opened to diners in early May, its name a tribute to ancient Italian folklore. The story of “la panarda” is rooted in Abruzzese culinary tradition, one featuring a gargantuan feast that seems non-ending. A typical panarda can feature anywhere from 35 to 50 courses served during the evening hours, sometimes until the next morning.

Each meal at La Panarda begins with a complimentary bruschetta and Aperol spritz. From there, diners are welcomed into VanTrece’s interpretation of a region of the world she loves. Italian tastes, flavors, and techniques with a little sprinkle of Southern soul.

For instance, VanTrece’s version of carbonara uses Berkshire pork cheek. Want ravioli? Look no further than the sweet potato ravioli on the menu, topped with toasted pecans and brown butter. There’s also oxtail osso buco paired alongside pecan gremolata and a collard green brodo that shines with smoked pork hock tortellini. Don’t miss the cornbread biscotti.

None of these renditions are purely traditional interpretations. But VanTrece wanted to expand her skill set and push herself at the same time. Though stretching herself in this way — what she refers to pushing the boundaries of expectation for her as a Black woman chef — was a challenge, there were parts of communing with Italian cuisine intimately for the formation of this restaurant that were reminiscent.

“I grew up in the Midwest in Kansas City,” she says. “Italian food was definitely something that we ate quite a bit of. I really didn’t get the connection or put the dots together until I was in Italy.”

Kansas City has a long history of being home to Italian American immigrants beginning in the 1860s. During that time period, most of the Italian immigrants hailed from Sicily. Immigration reached a peak some decades later, and by 1920, most of these families lived in the Columbus Park neighborhood, still known today as Little Italy.

This migration pattern, however, is not one that was only siloed in Midwestern and Northeastern cities and states. Within the South, Italian American migration was happening, too. New Orleans, for instance, had one of the largest populations of Italian Americans during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The reason for this is not random: During Reconstruction, as many Black people were leaving the South as refugees of persistent racial persecution, their absence of labor was profoundly felt. Italians hailing from Sicily and other parts of Southern Italy came in droves — a vast majority directly “recruited” from widely circulated advertisements the Louisiana Sugar Planters Association created. Once they arrived, they worked on ports, plantations, and even sharecropping on strawberry farms.

One way this culinary impact holds true still today is how folk from New Orleans make macaroni and cheese with spaghetti noodles, a leftover vestige of Sicilian influence. But historically, Italian Americans and Black Americans have always lived alongside each other, especially within urban sprawls — in New York, Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans. And it led to a cross-cultural exchange.

I really wanted to put Italian food and soul food — food I grew up with and am very proud of — together and see what came out … What made me feel real good when cooking it?— Deborah VanTrece

VanTrece was particularly motivated by the idea of not being boxed-in by what the industry at large expects for Black women chefs. Here, she is emboldening herself to be innovative, creative, and to have fun with food. Making it a practice of both mastery and play.

“I really wanted to put Italian food and soul food — food I grew up with and am very proud of — together and see what came out,” she said with a laugh. “What made me feel real good when cooking it?”

She knows the preconceptions that often loudly speak for her, especially being a Black woman cooking and leading restaurants in a major Southern city like Atlanta.

She knows that often people will leap to concluding that since she isn’t Italian, she can’t do what she is doing. Despite that, it was imperative to not limit herself in the same ways others do.

“I’m a chef,” she said. “And there’s really no cuisine I can’t do.”

Nneka M. Okona is a journalist living in Atlanta. Follow her at @afrosypaella. Follow Resy, too.