For the Siblings Behind Bánh Bánh, Tết Offers a Chance to Reconnect to Their Roots

At Bánh Bánh, their restaurants in Peckham and Brixton, the Nguyen brothers and sisters — Dung, Luan, Tien, An and Vi — reconnect with their Vietnamese roots through fish sauce-glazed chicken wings and life-affirming bowls of pho.

And growing up, the Nguyens took Tết, Vietnam’s Lunar New Year holiday, very seriously.

The family’s five siblings would watch as big stainless-steel pots came out of hibernation and their mother and grandmother began the annual days-long ritual of making an immense vegetarian Vietnamese feast for the family, who went meat-free on the first day of festivities in line with the country’s lunar calendar.

Alongside accepting red packets from their elders, dressing up in their best clothes and offering food to ancestors, the Nguyen children associated Tết with one dish in particular: bánh tết, steamed rolls of pork, mung bean and glutinous rice wrapped in banana leaves, which they would offer their friends and neighbours in Peckham, South London. The siblings were rarely allowed to stay up late, but Tết was an exception; longing for meat throughout the day, they’d wait until midnight for a nibble of bánh tết or Chinese sausage.

Decades later, Dung, Luan, Tien, An and Vi are still carrying on the tradition, albeit on a wider scale. In addition to enjoying a bountiful vegetarian feast as a family, restaurant guests can order bánh tết from the specials boards at the family’s eateries in Peckham and Brixton. Both sites are named Bánh Bánh, after the ubiquitous word preceding an almost limitless number of iconic Vietnamese dishes made with wheat or rice flour.

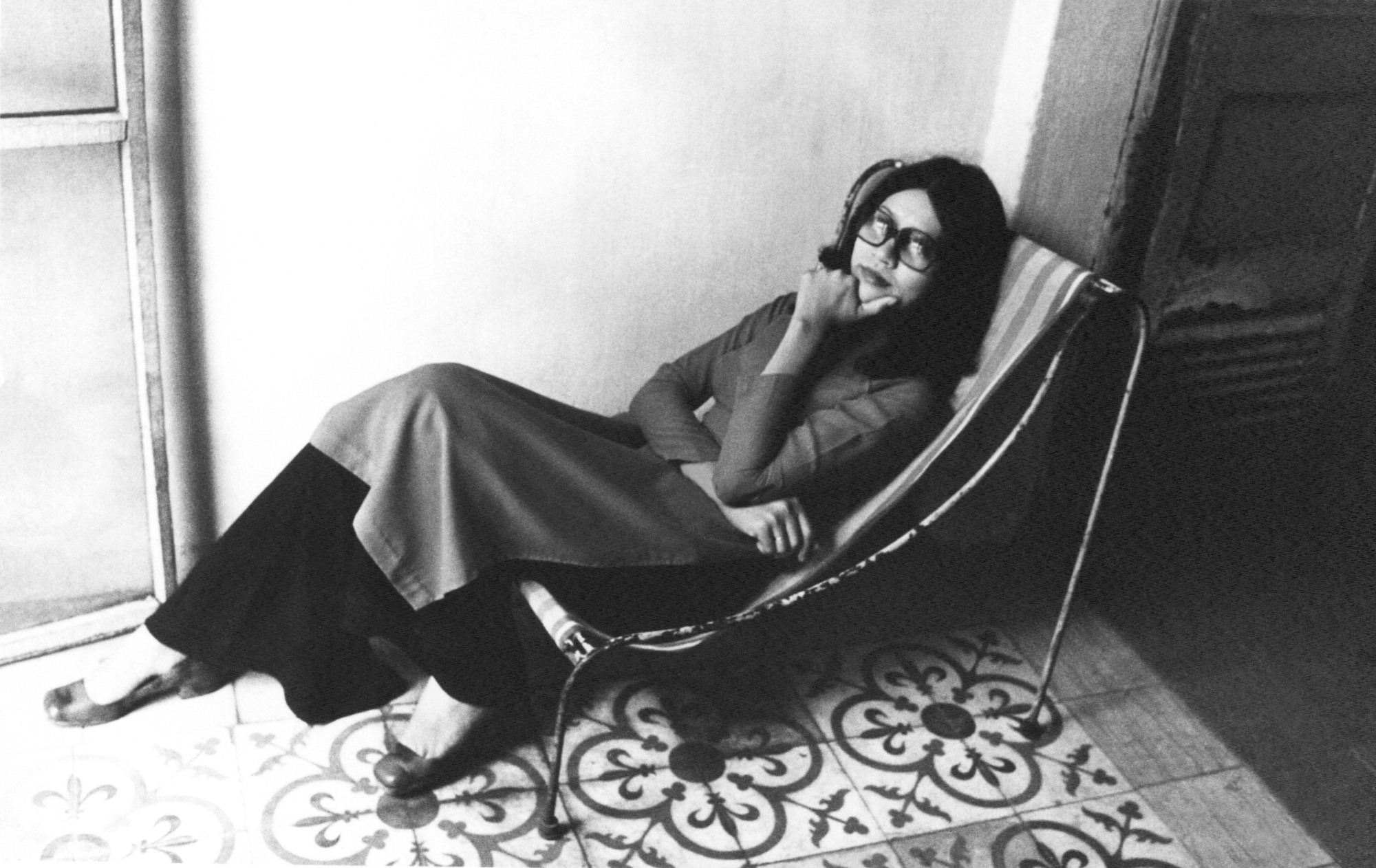

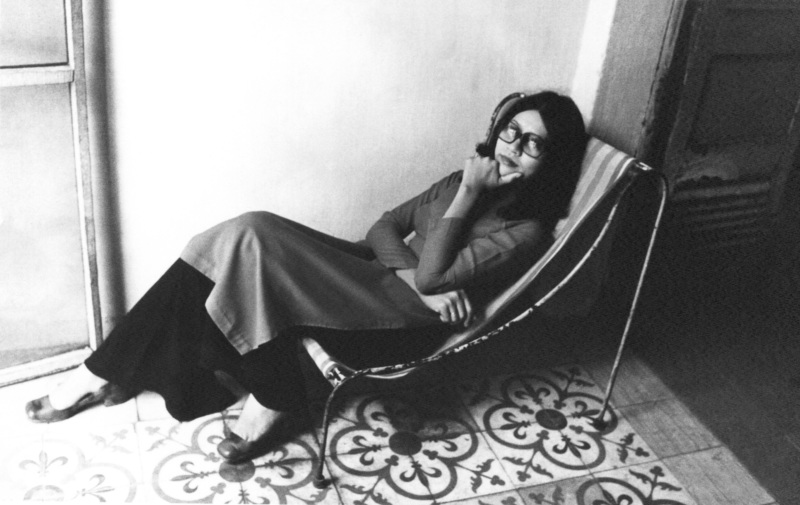

The family’s restaurants, which launched in 2017 and 2020 respectively, are homages to the siblings’ grandmother, who worked as a chef in 1940s Saigon. Over the years, Bánh Bánh has become not only a go-to spot for both homesick Vietnamese and Londoners new to the cuisine, but an ongoing dialogue between the second-generation immigrants and their motherland.

▪️

Hospitality was distilled into the Nguyen siblings from an early age. The family entertained often, and never without food; their home had, in essence, a revolving door, as friends went in and out and were fed in the process. “The fact that we could feed more people was always at the back of our minds,” says Tien Nguyen, the Peckham branch’s general manager.

Years of being urged by their parents not to pursue careers in restaurants — a well-worn but arduous path for Chinese and Vietnamese immigrants at the time — saw each of the siblings settle into nine to five jobs. But it was only a matter of time before pop-ups on weekends led to moonlighting at a Bussey Building residency for a year and a half. Finally, the siblings found their first Peckham site and took the plunge. Their parents eventually came around to the idea after seeing it from a different angle: it was to be a tribute to the matriarch.

Finding a location in Peckham was key. “We just wanted to share it with our friends, our friends’ families, our friends’ friends, so it was important to stay true to where we grew up,” says An Nguyen, who works a full-time job while overseeing the business’ marketing. “We wanted it to feel like a home away from home.”

“It’s really easy to lose that connection to your culture if you’re not surrounded by it” – Tien Nguyen

Proximity to the family home also allows the parents to drop in from time to time — their father, to help run errands, and their mother, to mediate any arguments that inevitably arise at a family-run operation, and to keep the siblings on their toes. “She’s our harshest critic, and never 100 percent happy because she’s an Asian mum,” Tien laughs.

The siblings recently relaunched the Brixton branch, where elder brother Dung Nguyen oversees the kitchen, to focus on Vietnamese street fare like prawn summer rolls and chicken curry. In Peckham, where food is led by second eldest Luan, diners will find Vietnamese classics, like pho and bánh khọt — their bestselling turmeric-hued mini prawn pancakes — alongside sharing dishes with a playful touch. “We’ve tried to keep the spirit of the food as it is, but inevitably we’ll have little twists we want to add to the food we inherit,” says Luan.

For example, the drinks on offer at both sites, led by Vi Nguyen, also riff on classic beverages with Vietnamese and Southeast Asian ingredients (or vice-versa), from rum-spiked Vietnamese iced coffees to fish sauce Bloody Marys. In Peckham, their guests regularly enjoy Huế chay, a vegan version of the iconic noodle soup bún bò Huế, with punchy fermented tofu used in lieu of shrimp paste. A concerted effort was made to introduce vegetarian and vegan dishes to Bánh Bánh’s menus, as well as regular meat-free Mondays, to mirror the vegetarian meals the Nguyens enjoyed at home occasionally in line with the Lunar Calendar.

▪️

As with many immigrant families, the siblings grew up eating some dishes with ingredients substituted out of necessity. Mangoes or cabbage would play the protagonist in their mother’s green papaya salad, and accessible ingredients, like eggs, pork and run-of-the-mill vegetables, would make up everyday staple meals. Special meals called for the hour-long bus ride to Chinatown, where Asian groceries were less bountiful and more expensive than they are today.

On occasion, the question of authenticity comes up. Tien recalls diners who have called their food inauthentic, based on having visited Vietnam themselves. But as she puts it, the family’s food is authentic to how they ate — including their southern Vietnamese roots and grandmother’s techniques, as well as what ingredients were available in 1980s Peckham. “We want the menu to showcase what we grew up eating — what is authentic to us,” says Tien.

With two sites under their belts, the Nguyens considered a third before the pandemic hit and slowed things down. But even amid the ups and downs of running two restaurants, representing their homeland as second-generation immigrants — and feeding people in the process — has rightfully become a point of pride, and a way to reconnect with their roots. “Food is the one strong link I have back into the culture I haven’t experienced first-hand,” says Luan, who bonded with his mother when learning how to recreate his grandmother’s dishes.

It’s a link not unlike Tết itself, which continues to bring Vietnamese families and communities together at home and abroad — something that is increasingly important to the Nguyens as they grow their families and pass traditions and dishes on to the next generation.

“It’s really easy to lose that connection to your culture if you’re not surrounded by it,” adds Tien. “We don’t really get to speak Vietnamese or experience the culture that much, but we stay in touch with it through cooking and feeding people.”

Zoe Suen is a freelance writer and editor based in London. Follow her on Instagram. Follow Resy, too.