Inheritance, Memories and Goulash: Dining With My Grandfather at The Gay Hussar

For the past year, I’ve worked as a cook in the basement kitchen of Noble Rot Soho, a restaurant and wine bar that opened in an old Georgian building on Greek Street in September 2020.

From the beginning, I’ve thought lot about the old building I work in. The inherited space has been refreshed to match its new owners’ sophisticated aesthetic, but its history is inextricably linked to The Gay Hussar, a storied Hungarian restaurant that formerly occupied the same walls. As establishments go, the Hussar carries a reputation and legacy you’re expected to know about – perhaps rightfully so.

Walking the halls each day and feeling old floorboards creak beneath my feet, I imagine who walked here before me. I can’t help but wonder who ate goulash 10, 20, or 50 years ago. I think about who butchered the beef, who poured the wine, who topped up the salt and pepper shakers on the table.

One autumn afternoon last year, minutes after being offered the job at Noble Rot, I sat in Soho Square and called my mother to share the news. I mentioned in passing the former restaurant that my newly-confirmed workplace now occupied, and she replied, as mothers tend to, with bated breath: “My god, Will – you do know that The Gay Hussar was your grandfather’s favourite restaurant? He called it his ‘canteen’!”

I was thrilled with this knowledge that had somehow slipped past me. I spoke with different family members who echoed my mother’s sentiment but didn’t offer much more information. I had to know more.

Now, as I prepare for service each day, with a busy dining room awaiting, I think about my grandfather and imagine what it would be like to dine with him at the old restaurant. And I imagine the half-century of memories that were created in that dining room, and the history that he and the Hussar’s other regulars passed down.

What was The Gay Hussar? And why did it matter to so many people?

▪️

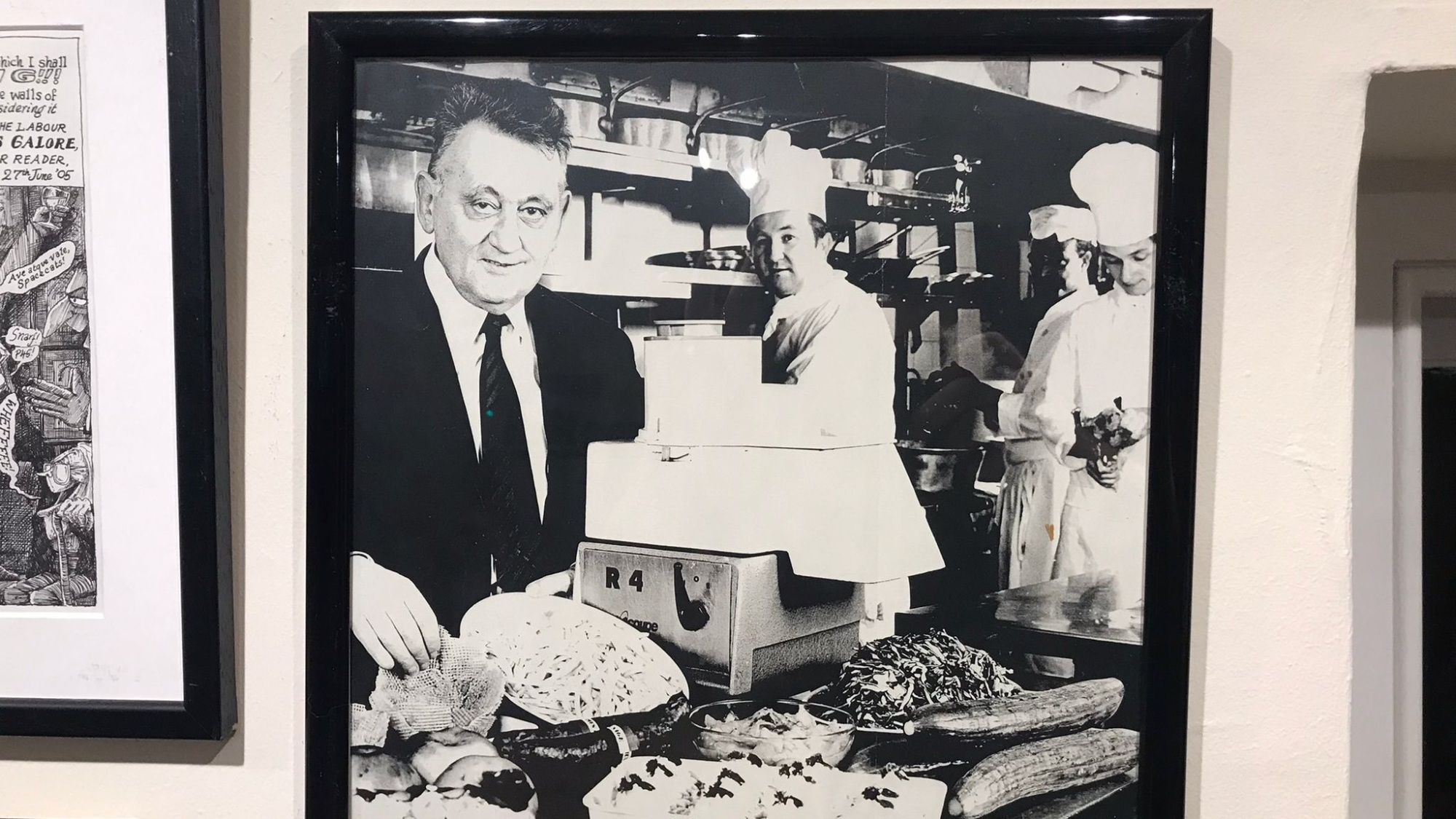

The Gay Hussar was opened in 1953 by Victor Sassie who, having worked at renowned Hungarian restaurants like Gundel in Budapest and Café Drei Husaren in Vienna, was informally bestowed the title of honorary Hungarian – despite being half Swiss and half Welsh, and hailing from Barrow-in-Furness.

Sassie ran the restaurant for over thirty years, where its primary draws were goulash and gossip. The Hussar became the home for Labour politicians, trade unionists, journalists – even the odd Tory MP. The dining room was a site of innumerable political plots, and where The Guardian thrashed out its leader line in successive general elections in the 1970s. It was, in short, a hive of deceit and political treachery. And its regulars knew that if you wanted a rumour spread, you told Sassie, who would have shared your darkest secret with the entire dining room by the end of lunch service.

Sassie sold the site to Corus and Regal Hotels that same year, before passing away in 1999.

Regulars knew that if you wanted a rumour spread, you told Victor Sassie, who would have shared your darkest secret with the entire dining room.

With his passing, I reached out to John Wrobel, the restaurant’s former general manager, who started working at the restaurant in 1988, before Sassie’s imminent departure. “Victor walked out of the building in 1988, at 14:10 on a Tuesday and never returned,” he says.

Over the next thirty years, Wrobel was the general manager at The Gay Hussar. He witnessed highs and lows, including some of the restaurant’s busiest periods, and its most difficult ones. Boozy political lunches slowed down, and generations of restaurant goers eventually died off. He tells me that once older generations passed on, their children and grandchildren usually stopped coming altogether.

And while the customer base changed over the 65 years of The Gay Hussar’s reign, sometimes the staff did not. From the early 60’s for over a thirty-year period, Laszlo Holecz served as head chef. In general, there was very little staff turnover, which hastened its decline as the times changed.

“They were set in their ways,” Wrobel says. “The same person was cooking. And it became impossible to refresh the menu.”

▪️

Regardless, Wrobel remembers some of the food fondly.

Admittedly, it wasn’t always good, and could occasionally be stodgy. But when it was good, it was great. “The beef goulash soup,” he sighs. “When made properly, it was just delicious!” Wrobel also loved the ‘Hungarian bouillabaisse’, as he calls it, a simple and very traditional Hungarian fisherman’s soup seasoned with noble sweet paprika.

A dish of stuffed cabbage with minced veal, pork and rice was another beloved staple; some customers would just have one plate and nothing else. One afternoon, Wrobel received a phone call from one Mr. Goldstein, a regular, inquiring how old the stuffed cabbage was. Wrobel replied that it was three days old. “In that case I’ll give it another week,” Goldstein bellowed down the line, implying the rolls only improved with a bit of age.

I’d like to think that what we do makes our guests happy in the same way the Hussar did for its clientele all those years ago

In a professional kitchen, a good roast duck or goose is difficult to execute but it was one The Hussar’s chefs accomplished regularly, serving it alongside red cabbage and apple sauce. It was usually ordered with a side of Hungarian potatoes, prepared by frying the potatoes in rendered smoked bacon or goose skin with onions and caraway seeds.

Wrobel also confirmed customers who dined often gossiped and goulashed in a conniving manner. “The place was home to misinformation and secrets,” he says. “Two men would come in, sit at different tables next to each other and occasionally have to switch, as they picked the wrong side. Bad ears.”

The last day of John Wrobel’s 30-year stint at The Gay Hussar was in 2018, when the restaurant shut its doors for good.

When Wrobel wasn’t working on Greek Street, he worked in other big hotels owned by Corus and Regal. He says when one leaves the staff quarters to enter the main lobby, there was usually a sign over the door that read “On Stage,” as one would find in a West End theatre. Although there was no sign in The Gay Hussar, he said it felt like there should have been one – “working there always felt like a performance.”

▪️

Which brings me back to my grandfather, Peter.

He was an illustrator and lectured at Central School of Art and Design (now part of Central St. Martins) for fifteen years on the Charing Cross Road, one street over from The Gay Hussar.

My grandmother, Françoise, fondly recalls eating in the restaurant with him, and confirmed he was a regular, often dining alone or joining friends impromptu. He was also very friendly with Victor Sassie, whom my grandmother describes as “always there. Old, not thin. Rather plump. Very kind and cheerful.” On one occasion, my grandfather decided to steal an ashtray from the restaurant, now one of my most treasured possessions.

But while Peter and The Gay Hussar are long gone, with any traces slowly fading away, the old restaurant served the clientele of its era for many years and accumulated more history and achieved more success in its time than perhaps any other in the city. It lives on in verbal recollections, occasional homages, Martin Rowson’s collection of paintings (recently donated to The National Portrait Gallery) and in eccentric family heirlooms passed from one generation to the next.

Perhaps, then, a kind of inheritance is what remains.

The building will forever be an heirloom, one which Noble Rot have inherited to honour for, hopefully, a long tenure. The food we cook and the wine we serve are steeped in tradition, history, and nostalgia, with the utmost respect for its previous occupant, but our gazes are focused on the future.

I’d like to think that what we do makes our guests happy in the same way the Hussar did for its clientele all those years ago. The Gay Hussar was of its time in the way that Noble Rot and others are indicative of the present.

As for me, I’ll continue to cook in the basement of 2 Greek Street, thinking about Victor Sassie welcoming in my grandfather, and Laszlo Holecz preparing a plate of goulash for him. As many have before me, I’ve now inherited this kitchen floor and walls, these floorboards, and the spirit of a cherished institution – it’s now my responsibility to cook good food and honour that history as the cooks after me should do with the same fervour.

I never stepped foot in the building whilst it was The Gay Hussar. And although I feel very connected to the space and energised to be here, I will never gaze upon those bright paprika red walls. I wish I could experience it, just once – but I can’t. I will never share a meal with my grandfather. But if I had, I imagine he would have ordered goulash.

Will Stewart is a cook and hosts A Cooks Library, a podcast about life in the kitchen.