Wylie Dufresne Finds His Ultimate Challenge (Spoiler: It’s Pizza)

During the thick of the pandemic in 2020, at his home in Lyme, Conn., Wylie Dufresne unearthed a box in his basement that contained an unused Breville Smart Oven Pizzaiolo. He’d bartered for the oven at some point and had completely forgotten it was even down there, but at this moment it was kismet. For the next eight months, he made pizza multiple times a week for his family. And by last spring, in 2021, he’d formulated a concept for Stretch Pizza, which now holds tenancy at Breads Bakery on East 16th Street, just off Union Square in New York City.

A chef whose career has been defined by a phrase he feels is misunderstood (see: “molecular gastronomy”), he wowed the culinary world with his decade-long run as chef-owner of wd~50 in the Lower East Side. In 2013, he finally — and deservedly — won a James Beard Award the year before he closed the restaurant. Many considered what he was doing there “the future of food,” so it was a surprise — especially to Dufresne himself — that pizza would be his renaissance, by way of not reinventing the New York slice, but rather, trying to understand it.

- Behind the Scenes at Stretch Pizza

- Una Pizza Napoletana Is Coming Back. This Time, Only in New York City.

- Al Di Là’s Anna Klinger on the Magic of Brooklyn, and Staying Power

- How to Get Into New York’s Saint Theo’s, and What to Order

- The Resy Guide to New York’s Essential Cozy Locales

- Ops’ Mike Fadem Wants You to Order Salad and Wine with Your Pizza

Stretch Pizza was born out of the pandemic and perhaps, boredom, since all his other restaurant gigs were on hiatus, but Dufresne’s framework for what pizza is — or ought to be — was established during high school. He attended Friends Seminary, also on East 16th Street, in the East Village. At that time, he frequented Mariella’s, which was clad in a faux Amalfi–like seascape decor, for a “sloppy” regular slice with “too much cheese” and Famous Ray’s Original on 11th and 6th Avenue for a Sicilian square. Like so much, pizza is especially formative during those years and that proved true for Dufresne.

The problem, Dufresne points out, with the current state of many New York-style slices is that there’s been little to no progression in those classic pizzerias; they operate with a tired checklist of forgone conclusions — meh flour, sauce, and cheese. With Stretch, Dufresne is hoping to change all that.

▪️

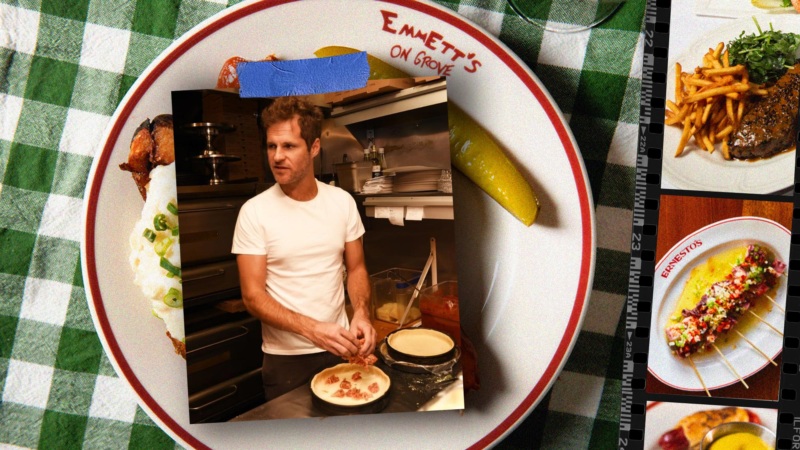

Today, he stands in the Breads kitchen beside Josh Eden, his high school friend, and lifelong New York City chef as well (August, Shorty’s 32), whom he convinced to become his pizza “launcher” (someone who builds pizzas on a conveyor belt-like contraption, that then slides said doughs onto the floor of the ovens). Most days, Dufresne, unironically, wears a red hat, the same hue as pepperoni. Both are surrounded by generic brown pizza boxes with the Stretch sans serif script stamped on top, and rolling racks filled with small round takeaway containers, each holding 250-gram dough balls ready to be shaped. They’re joined by Matt Birnbaum, who previously owned Pinch—Pizza By The Inch, and now works expo, cutting each 12-inch pie into six slices at well-practiced 60-degree angles. To round out the team, Dufresne hired Jimmy Leonor, his production cook from Du’s Donuts & Coffee, which remains temporarily closed. Leonor is now here to stretch and dress each pie.

The name Stretch itself is a call to attention. Dufresne’s biggest fixation about pizza is currently the crust: He believes we’ve taken it for granted for way too long.

“Watching bad pizza being made or built is still mesmerizing, even though it might not taste good,” he says. He’s trying to reconcile how dough can be both flavor and function.

When Dufresne really wants to understand something, he tackles it from a science angle first, which proved frustrating when it came to pizza dough. The shortcoming, he proclaims is “the lack of science around days-long cold fermented pizza dough.” (He did, however, recently give a lecture at Harvard called “Pizza — Lost in the (Gluten) Matrix,” about exactly that.)

He initially started his pizza education via King Arthur Baking Company’s website, and of course, clicked on the recipe for Thin-Crust Pizza (King Arthur’s New York-style), first. “It was the only pizza I have reference for.” From there, it was trial and error. “I’m not a fan of ‘any pizza is good pizza;’ that’s disrespectful to high art pizza-making,” he says, as he walks away to bring a pizza out front for a pickup order.

With Eden, Dufresne discusses his philosophy on how pushing carbon dioxide from the middle of the dough creates a better inner tube on the exterior. Eden, whose nickname is “Shorty,” is 5’4” and stands eye-level to the third-tier of the Bongard Omega bakery deck oven. He works methodically, rotating pies around the hot spots, and dropping them from higher decks down to lower ones to ensure the crusts don’t cook too quickly. All the while, the cheese and toppings broil into a congruous canvas with every pie.

“We [New Yorkers] view pizza as an interim meal — grab two slices mid-afternoon, and you’re good until dinner,” says Eden. “Pizza can be a little bit of a trap … but not for two guys that are from New York.” During the pandemic, he and Dufresne would have Zoom conferences on dough, and the two would stretch together online in tandem.

Today, Dufresne attempts to grasp all three corners of the pizza crust trifecta: Neapolitan’s chewy pull, Sicilian’s thick crust with its airy crunch, and New York-style thinness. The canon of his crust is one that shouldn’t quite shatter, but an audible crunch is a prerequisite. When asked for his dough recipe, he scoffs, as if it’s a secret because, well, it is. “Your dough matures in flavor, aroma, and physical changes,” he says. Dufresne’s dough is still in its formative stages, but it’s also maturing beyond its single year and a half of existence.

Even though Dufresne says that pizza is a new thing for him, it was on his mind even back in his wd~50 days. It was a staple for staff family meals and a joint effort. Dufresne would ask Alex Stupak, his longtime pastry chef, who now owns the Mexican-inspired Empellón empire in New York, to make the dough. His garde manger chef made the sauce. The entremetier prepped the meat and toppings.

Pizza was once on the wd~50 menu, too, in a dish called “Pizza Pebbles.” It was all of the components of pizza in powdered forms — garlic, tomato, milk, Parm, mozzarella, and breadcrumbs — served with a chorizo emulsion and mushroom chips. Dufresne admits the pebbles were very polarizing: “A lot of people thought they tasted like the pizza filling from Combos.”

▪️

As the orders come in at Stretch, the dough is systematically formed into rounds. Dufresne exclaims, “We’re not reinventing the wheel here.” Eden and Leonor work their fingertips around the edges, then the dough is moved to the top of their hands, draped atop their knuckles, stretching in the air, letting gravity do the work. Everything has to be done in a timely manner but looks as leisurely as pizza should feel.

For every launch of the pizza pies, Eden sets the timer for six minutes, but leaves most pies in for at least eight. He’s looking for an evenly browned bottom, with what Dufresne describes as “micro-bubbling” around the edges.

“A lot of pizza’s success is expanding the umami zone: sauce, cheese, and fermentation [of the dough], right?” Dufresne asks. His is a classic sauce of New Jersey crushed tomatoes, but Dufresne being Dufresne, he adds a little xanthan gum for viscosity, too.

Whereas he’s tight-lipped about his dough, when it comes to cheese, “that’s not the place to guard your secrets,” Dufresne says. His is a big blend of pre-shredded Grande mozzarella, some full fat, some skim, and a 50/50 bag of skim and provolone, “for tang.”

In a more innovative approach to cheese-ing a pie, Dufresne uses a slurry of cream cheese thinned with milk and a handful of aged mozzarella as the basis for his Everything Bagel pizza, finished with sprinkle of everything bagel spice and a flurry of chives. It tastes just like an everything bagel with cream cheese, as one would expect. Another pie, the Oddfather, gets covered with a smoked eggplant puree and topped with aged mozzarella, spears of roasted zucchini that have been seasoned with Italian spice, and tempura flakes that taste like Italian breadcrumbs that are liberally poured atop the pizza.

Eden is cutting scallions for November’s collaboration pie with Simone Tong of Silver Apricot, a New-American-Chinese restaurant. This pizza, called the Humble Pie, is topped with pickled daikon, aged mozzarella, maple-chile sauce, and the aforementioned scallions.

The team is workshopping a new pie, tentatively referred to as the “Fennel,” utilizing all parts of the herb: pollen, fronds, and fennel lemon puree. Both Eden and Leonor think it tastes light and refreshing, which isn’t something you’d normally say about pizza. “We’re doing a good job with toppings,” quips Dufresne, who still won’t give himself a commendation on his crust.

Dufresne hopes to expand Stretch to a permanent brick-and-mortar, and is already on the lookout, if not having nearly secured a space. He hopes we all sit down for pizza more often, rather than grab-and-go. That we all take a piece of the communal pie.

Chewing quietly with Bob Dylan’s “Rolling Stone” playing in the background, Dufresne contemplates his crust in-time with the lyrics, “how does it feel” — lyrics that reflect what he went through: losing his livelihood, and yet, finding freedom in reinvention.

“At the end of the day, pizza saved me,” Dufresne grins. Then he cuts another slice and takes a bite, believing he can still do better.

Stretch Pizza will be on a brief hiatus for the Thanksgiving holiday, but will return to Breads Bakery on Dec. 7. The pop-up runs Tuesdays through Thursdays from 5 to 8 p.m. and you can reserve your pizzas to go here.

Michael Harlan Turkell is a photographer, writer, and cookbook author. He’s also host of the recently launched Modernist Pizza Podcast, which explores the art, history, and science of pizza. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter. Follow @Resy, too.